Content warning: The article contains references to trauma and the Holocaust, which might be upsetting to some readers.

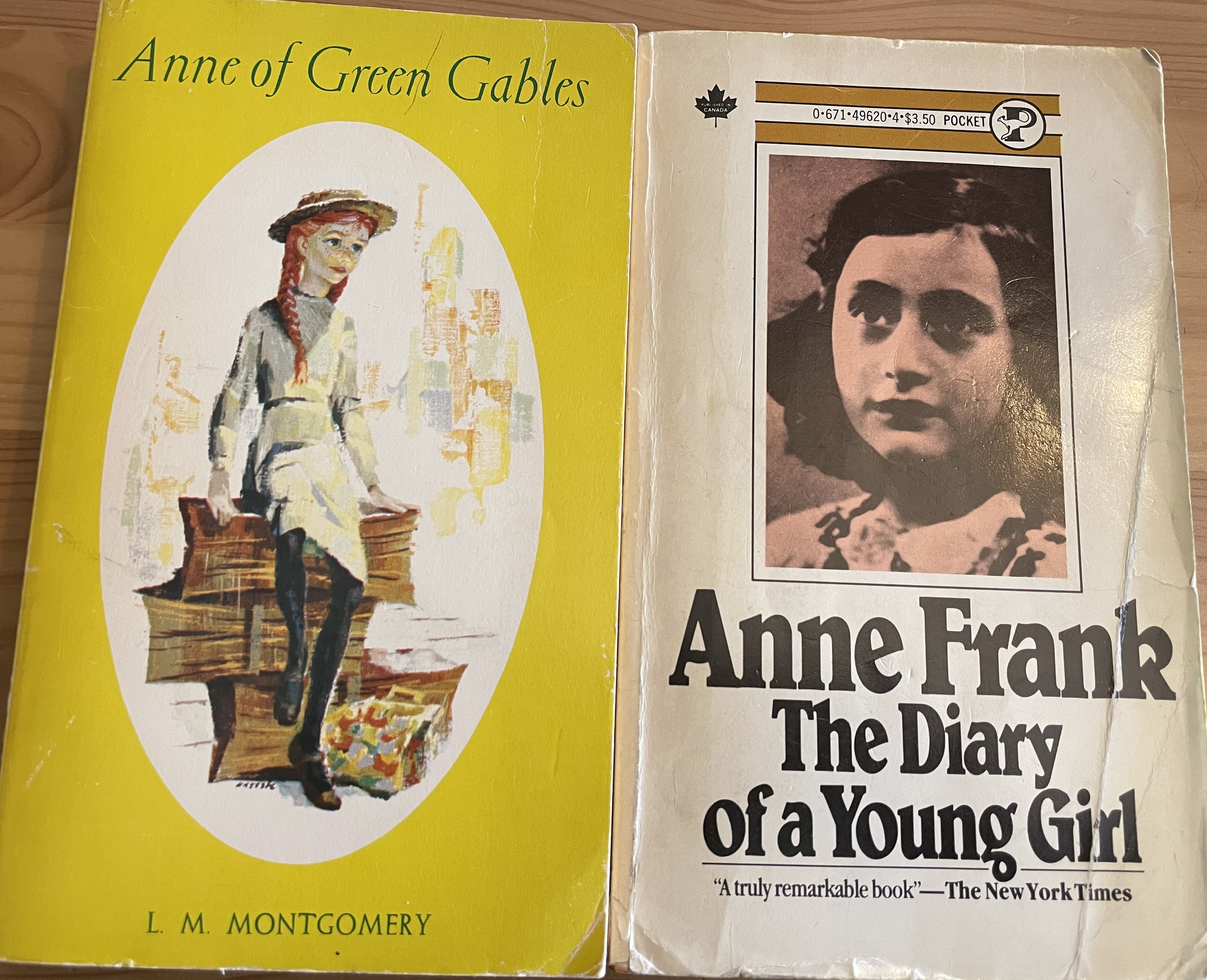

L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables and Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl are books that many read when they are young. This essay is a reflection on how reading and studying these two books influenced my writing life and process. It compares the authors’ approaches to life-writing and revision, giving a brief comparison of each, and analyzes how this type of exploration offers a deeper understanding of how these authors approached their writing as well as how their work could be used as mentor texts for other writers.

“There’s such a lot of different Annes in me. I sometimes think that is why I’m such a troublesome person,” Anne Shirley tells Diana Barry in Anne of Green Gables.1 Similarly, in The Diary of a Young Girl—a teenager’s autobiographical account of hiding from the Nazis during the Second World War—Anne Frank recounts the many Annes within herself: “The happy-go-lucky Anne laughs, gives a flippant reply, shrugs her shoulders and pretends she doesn’t give a darn. The quiet Anne reacts in just the opposite way. If I’m being completely honest … I’m trying very hard to change myself, but that I’m always up against a more powerful enemy.”2

One is a fictional character. The other, a person who lived.

One survives. The other did not.

Right: Photo of Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, 1947. Simon and Schuster, 1958. Private collection, Melanie J. Fishbane, 2021.

I was deeply influenced by both L.M. Montgomery and Anne Frank. Their writing has provided me an opportunity for creative exploration and to examine the different “Annes” in me through my own work. My perceptions of Anne of Green Gables and The Diary of a Young Girl have been influenced by reading both books for the first time when I was nine. As a young writer, I searched for literary models to learn from. I searched for stories that discussed writing, finding characters who told and wrote stories. I searched for survivors and storytellers. And, when I started to keep a journal at twelve-and-a-half, I was heavily influenced by not only how Frank organized her entries by addressing them to “Kitty,” but also how she introduced herself to the journal as a friend. Later, delving into Montgomery’s journals in my mid-teens and early twenties cemented the importance of journal writing for mental and emotional balance and as a record of my life. This paper is a reflection on how Frank and Montgomery’s work influenced me as a writer, and it will explore how Montgomery and Frank approached writing. First, I will discuss how I was introduced to both books, and then I will address my approach to journal writing as a teenager. Then, as this has been extensively covered by Montgomery scholars, I will offer a brief reminder of Montgomery’s life-writing and process, followed by an explanation of the various versions of The Diary of a Young Girl and Frank’s approach to revision. The essay will conclude with an exploration of how these books can be used as examples of mentor texts, books that other writers can study to learn about the writing process and craft such as dialogue, description, and character.

Meeting the Two Annes

Confession. When I first read Anne of Green Gables, I did not finish it.

As a Jewish girl growing up in Canada during the 1980s, there was never a time in my life when I did not know about the Holocaust or the idea of hiding my heritage so that no one would know where I came from. In Survivor Café: The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory, Elizabeth Rosner examines her identity as a daughter of Holocaust survivors and how this relates to the study of transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, whereby the trauma of a previous generation is passed down to subsequent generations.3 According to a study conducted by psychologist and neuroscientist Rachel Yehuda on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among descendants of Holocaust survivors in Israel, these children and grandchildren still carried their grandparents’ and parents’ trauma, suffering from anxiety and depression. Yehuda concludes that their PTSD was “‘inexplicable’ by any other means than intergenerational trauma.”4 While I am neither the daughter nor granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, I am a cousin and great-niece of those who simply, as my grandmother would say when showing me old photographs, “disappeared.” I am not trying to put myself in a special category nor compare traumatic experiences, but, having spoken to other Jewish people of my generation, a fear and anxiety connected to the Holocaust is very common. We carry the ancestral trauma of being part of a religious community that has been a victim of genocide. We always make sure we have an escape route or a place to hide under the stairs, at the back of the closet, or under the bed. I live with the knowledge that the only thing neo-Nazis care about me is that I am a Jew. And they want me dead.

This fear has been particularly relevant lately with the increase of anti-Semitism and political populism, such as the shooting at the Tree of Life—or L’Simcha Congregation—synagogue in 2018,5 the presence of neo-Nazi ideology in Germany during an anti-COVID-19 protest,6 and the violent uprising at the White House on 6 January 2021, which included white-supremacist groups wearing anti-Semitic iconography.7 These events remind me of the anti-Jewish sentiments that eventually led to the Spanish Inquisition, the pogroms of the late-nineteenth century, and the Holocaust. Growing up in a religion that is steeped in more than 5,000 years of history, and persecution, these stories are not just part of my cultural upbringing, but it is as if they are imprinted on me, like my grandmother’s hands. These stories are in my ancestral DNA.

As a person who has never been part of the dominant Christian religion, I have always been aware of my position as “other.” Often told, “But, you don’t look Jewish,” and having white skin means I do have the privilege of coding to the default dominant white Christian culture. However, the statement itself that I do not “look Jewish” shows that people have preconceived notions of what a Jew might look like—such as a dark complexion—and these are features that anti-Semitic groups use to define our “race.” For personal and spiritual reasons that are much too involved to discuss in this essay, I have chosen to not follow Jewish Orthodox or Modern Orthodox dress codes, making it easier for me to blend in. Thus, even while seeing myself as an outsider, I do not experience the daily prejudices that Jewish Orthodox and Modern Orthodox or other more visible religious minority and racialized groups do. I have a choice to hide who I am, and there is privilege in this. For example, in 2019, when attending a symposium on Jewish children’s literature at the Highlights Foundation, depending upon whom I spoke to, and how safe it felt, I would either say it was a “symposium” or “Jewish symposium.” My decision tended to be based on whom I felt safe with and was not necessarily something I could quantify. I was always wary of “outing” myself. This was a deliberate way of me using my privilege to protect myself against a perceived threat. With this essay, I somehow find myself stepping publicly into my Jewish identity and acknowledging how it played a big part in how I interpreted Anne of Green Gables and The Diary of a Young Girl. This essay makes me feel very vulnerable, putting myself out there for ridicule by people who may not understand or respect my feelings, or taking the risk of possibly facing anti-Semitic attacks. But, writing through this fear is my way of hopefully beginning to work through and heal from generational trauma.

A generational trauma that in 1982, when I was a nine-year-old reader, was firmly part of my upbringing.

By the time my grade four class attended our weekly library period at the Jewish day school I attended, I had already taken part in a number of Holocaust Memorial Days, which included exhibits featuring pictures from concentration camps. It is also very plausible that I had watched the 1980 TV adaptation The Diary of Anne Frank, starring Melissa Gilbert. Given that my mom and I watched Little House on the Prairie together each week, in which Gilbert played Laura Ingalls, we probably watched the TV movie together on NBC. Suffice to say, by the time the librarian showed my class The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank’s name and experience had already been etched onto my consciousness.

The librarian also recommended Anne of Green Gables, and I was interested because the gender mix-up intrigued me, and (I am sad to say) it was one of the first books I had ever heard of that took place in Canada. As a Canadian that was also exciting. As a voracious reader, of course I borrowed both.

I read The Diary of a Young Girl first. Then, I turned to Anne of Green Gables. Thirty pages in, I put it down and did not pick it up again until three years later when I was about twelve. The combination of an unwanted Anne and a stern Marilla who put her new charge in the “little gable chamber”8 must have brought visions of another Anne in an attic, and I read the word “chamber” as “gas chamber.” While I realize this initial interpretation of Anne of Green Gables was incorrect, even now I still have the visceral memory of what my initial misreading felt like, and I have to remind myself that is not what it says. So, I put the book away and did not pick it up again until I saw the Kevin Sullivan television production in 1985. It was then that I discovered how (unlike Anne Frank) Anne Shirley survives to adulthood. Perhaps it was the pastoral landscapes or that I watched it in the safety of home with my mother (or because I thought the actor who played Gilbert Blythe [Jonathan Crombie] was cute!), but I had a new appreciation of the story and returned to the novel.9 It was then I saw how Anne Shirley uses her imagination not only as a coping mechanism but as a way to inspire those around her and to make a life for herself. She receives a higher education but also becomes a teacher, experiences the thrill of having a few of her stories and poems published, and eventually marries the man she loves. I no longer equate Anne Shirley with the Anne hiding in the attic. Still, as you are about to see, whenever I dipped back into Anne Frank’s life, Anne Shirley or L.M. Montgomery or both were also there.

Being the Writer in the Attic

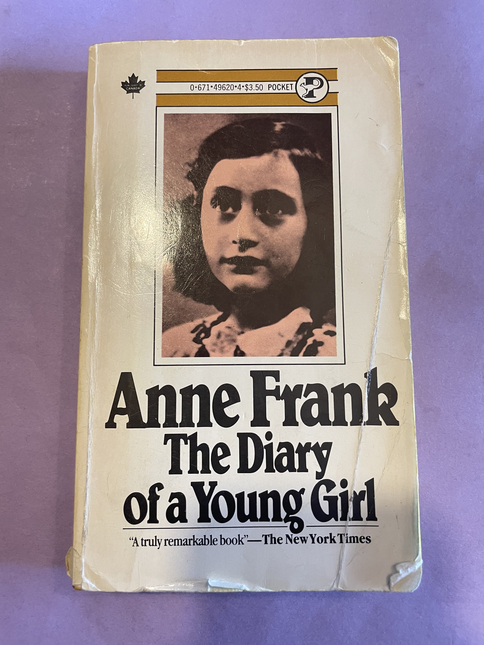

I have kept a journal since I was twelve-and-a-half years old. A gift from my grandmother, the first book is pale blue, with a castle perched on top of a cloudburst and a rainbow leaping into the unknown.

Right: Photo of Melanie J. Fishbane’s journals during teen years. Private collection, Melanie J. Fishbane, 2021.

Perhaps I saw the parallels between this gift and the diary that Frank received for her thirteenth birthday, right before she went into hiding, and our shared desires for a trusted friend and confidant, but I immediately remembered Frank’s book and subconsciously used it as a model of how to start my own. When she started the diary, Frank hoped, “To enhance the image of a long-awaited friend in my imagination, I don’t want to jot down the facts in this diary the way most people do, but I want the diary to be my friend, and I’m going to call this friend Kitty.”10 Following Frank’s guidance, at twelve-and-a-half, I introduced myself to my journal, told it how much I hoped it would be a trusted friend, and knighted it “Special.” In the following entry I explain why, “for one thing I’m going to tell you everything about me and my feelings … And your [sic] going to be Special.”11 Over time, my journal evolved from declarations of love for boys who were not worthy of me and dramatic stories of fair-weather friends, to (what I hope were) deeper explorations of my spiritual and emotional well-being, and, yes, to ranting when necessary to an invisible, non-judgmental audience. Most recently, during the COVID-19 pandemic, I filled two notebooks (and have started on a third) that were begun in March 2020. It is my life—or one version of it—in pen and ink.

Throughout my life, Frank’s and Montgomery’s life-writing provided me with models of how I could approach my own record keeping. In fact, in preparation for this essay, I combed through the first fifteen years of my journal (1986–1999) to see if and when I discussed their works. As I will explore in the next section, both writers revised and edited their work, and, in Montgomery’s case, she kept her journal from the age of nine until her death in 1942. During particular life events, like the COVID-19 pandemic, I think about how Montgomery meticulously discussed what was happening during the First World War, and Frank’s approach to writing about her life in the Secret Annex. Please note, I am not comparing the COVID-19 pandemic to Frank’s experience—as some people on social media have done12—because I have the privilege of leaving my house and getting groceries with minimal physical danger, but the idea of record keeping has made me quite aware of the importance of writing during times of political unrest and personal distress.

As mentioned previously, inspired by the Kevin Sullivan miniseries aired in 1985, at twelve years old I decided to return to Anne of Green Gables. Since then, Anne Shirley and other Montgomery characters are a safe haven for me because Anne Shirley survives her trials and tribulations. Sometimes I have returned to Montgomery’s work for pleasure, and often times for academic purposes, as studying her writing has become a big part of my personal and professional life. Anne of Green Gables is less traumatic for me to read and study than The Diary because, while the novel explores issues of gender equality and class, it finishes with its heroine gazing out her window, contentedly reflecting upon her accomplishments and what roads lie ahead. Quoting Robert Browning, Anne whispers, “‘God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world.’” In this moment, there is a vow that “nothing could rob her of her birthright of fancy or her ideal worlds of dreams.”13 There is hopefulness and an understanding that even past the bend in the road, Anne Shirley has Green Gables and kindred spirits and is excited about the unknown possibilities that could only lead to a bright future.

Conversely, this essay is the first time I have read The Diary of a Young Girl for intellectual or creative purposes. While I remember connecting with Frank’s descriptions of being a confused teenager and her romance with Peter, her experience is different from my own adolescent experience: she is a person in hiding from a government that wants her and her family dead.14 Frank’s diary abruptly ends after a self-reflective meditation on her feeling “split in two.” Her final words are about her struggle to become “what I’d like to be and what I could be … if only there were no other people in the world.”15 In the edition I read when I was nine, there is a short epilogue in italics describing what happened to Frank and her family, how Anne died in a concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen in March 1945.16 Therefore, The Diary of a Young Girl ends because its author was arrested and then murdered. The author never had a chance to finish her diary or the life it recorded because her family was captured by the Nazis and murdered. There is no romantic bend in her road. Her road just ends.

Controlling the Narrative

As Sharon Darrow discusses in her craft book Worlds within Worlds: Writing and the Writing Life, good writing helps readers connect to some element of social, emotional, or psychological truth:

We are all unique because of our own individual experiences; our familial, genetic, and societal backgrounds; the geographies we’ve experienced through travel or residence … we have different wells of emotion and different reasons for coming to writing as the art of our life’s expression. Each of these things affects how we make stories, how we experience our characters, and how we choose the diction, tone, and voice of the pieces we write.17

Both Montgomery and Frank are using writing “as the art” of their “life’s expression.” Rather than simply relying on the autobiographical fallacy, which suggests that writers are fictionalizing their life, but without considering their talent for creating fictional worlds, scholars can focus on these authors’ work as mentor texts and learn about how they approach the craft of writing.

The challenge comes, however, when distinguishing between Montgomery and Frank, the writers and their characters, because both the media and scholars conflate the two, invoking the autobiographical fallacy. In the case of the media, this is frequently to encourage tourism. For Montgomery there are often correlations between her real life and her fiction. For example, as part of a marketing campaign for Kevin Sullivan’s book and miniseries Anne of Green Gables: A New Beginning, Andrea Pacheco discusses the “parallels” between Montgomery and Anne Shirley, such as how they were both orphans and how they both used writing to take “solace from the harshness of the world.”18 Similarly, in a newspaper article, Marylou Tousignant describes how “Anne of Green Gables is very much alive in Canada” by highlighting how “Montgomery, like fictional Anne, grew up in Prince Edward Island, a small province in eastern Canada. Left parentless as a child, she was raised by elderly grandparents who were gloomy and strict.”19 In Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery, Elizabeth Waterston describes the two worlds Montgomery inhabited while writing Anne of Green Gables: “Avonlea fiction” and “Cavendish reality, such as the Green Gables house, or places found in the book, such as Lover’s Lane.”20 In her memoir The Alpine Path, Montgomery writes about how the Story Club in Anne of Green Gables was inspired by a “little incident” during school.21

Similarly, the “real” Anne Frank and her diary have been complicated by Otto Frank’s and others’ editorial decisions contributing to how Anne Frank is often perceived: as an idealistic person who believed “people were good at heart.” As Erin Blakemore points out, Frank’s quotation is often taken out of context. It occurs toward the end of the diary (15 July 1944) after a long meditation in which Frank pours out her frustration over the war and her own contradictory nature; Blakemore questions the mythology that surrounds Frank as a positive and idealistic person, when the reality is the writer was often prone to “darker moods.”22 Cynthia Ozick’s “Who Owns Anne Frank?” made Ozick one of the first authors to criticize Otto Frank’s editorial approach (and subsequent adaptations):

And because the end is missing, the story of Anne Frank in the fifty years since “The Diary of a Young Girl” was first published has been bowdlerized, distorted, transmuted, traduced, reduced; it has been infantilized, Americanized, homogenized, sentimentalized; falsified, kitschified, and, in fact, blatantly and arrogantly denied. Among the falsifiers have been dramatists and directors, translators and litigators, Anne Frank’s own father, and even—or especially—the public, both readers and theatregoers, all over the world. A deeply truth-telling work has been turned into an instrument of partial truth, surrogate truth, or anti-truth. The pure has been made impure—sometimes in the name of the reverse. Almost every hand that has approached the diary with the well-meaning intention of publicizing it has contributed to the subversion of history.23

Ozick argues that this “subversion” makes it easier for readers to distance the girl in the text and the young writer who is eventually murdered at Bergen-Belsen. Ozick suggests, too, that Otto Frank preferred to focus on Anne Frank’s message of hope, rather than hate, because (as a German Jew) Otto Frank grew up with the need to “please his environment” by “not offending it.”24

In her book Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife, Francine Prose discusses at length the drama surrounding the play adaptation of the diary—including multiple authors, a lawsuit, and “at least four books” that attempt to explain how the 1955 theatrical adaptation The Diary of Anne Frank by Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett was conceived. Prose explores how an attempt to make the story more “hopeful” and “universal” makes Frank seem rather silly and spoiled, rather than seeming a thoughtful young adult who was developing her craft.25 And, as both Ozick and Prose discuss, it is this frivolous version of Anne Frank that brought more people to the diary. According to Prose, the 1997 adaptation by Wendy Kessleman starring sixteen-year-old Natalie Portman is more faithful to the diary and ends with Otto telling the audience how Anne died. But, possibly inspired by Portman’s performance, the reviews focused on, as Molly Magid Hoagland put it, “flirtatious, idealist Anne Frank.”26 Ari Folman and David Polonsky’s 2018 graphic novel adaptation is based upon Mirjam Pressler’s Definitive Edition of the diary, edited and updated in 1996. As Ruth Franklin’s review articulates, the graphic novel shows the diary’s comedic moments and Polonsky’s haunting illustrations juxtapose the world inside the Secret Annex and Anne imagining what is happening outside it. For example, when Frank is questioning the point of war and destruction, Polonsky creates a series of six panels corresponding to what a contemporary reader might know about the Second World War. When Frank writes, “Why are millions spent on the war each day,” the artist links Frank’s critical questioning of violence with images of women (some possibly close to Anne’s age) building bombs for the military-industrial complex, providing readers with a possibility of the kinds of things Anne might have been thinking about.27 This image is also a reminder that had Anne Frank been born elsewhere or had she not been Jewish, she could very well have been one of those women building bombs. However, as Franklin also points out, the two creators miss the opportunity to represent Frank as a writer and do not often show her composing the diary:

Folman and Polonsky depict Anne as a schoolgirl, a friend, a sister, a girlfriend and a reluctantly obedient daughter. But only once, at the close of the book, do they show her in the act of writing. In so doing, they perpetuate the misconception about the book that so many have come to know, love and admire—it was, in truth, not a hastily scribbled private diary, but a carefully composed and considered text.28

Therefore, the play, movie, and other adaptations of Frank’s diary have continued to perpetuate the notion of an idealistic and naive girl, ignoring her writerly ambitions and the reality of her experience of fear and persecution—and her eventual murder.

It is also important to recognize how Montgomery and Frank contributed to their own mythology by shaping their journal and diary respectively. Montgomery and Frank’s approach to their journal-writing process opens up some interesting questions as to the kind of (life) story they wanted to tell, as well as to how readers themselves engage with the authors’ works and participate in perpetuating certain ideas about the authors and their works. Montgomery was meticulous about what she left behind: her copied journals, a cookbook, scrapbooks, her personal library, and other family mementoes, but other things—like her years of correspondence and her original journals—were burned. She was conscious of her significant place within the Canadian literary landscape and planned accordingly. In 1919, Montgomery began copying out her original journals, which were “blank books of varying shapes and sizes,” into large ledgers and finished on 16 April 1922, leaving very specific instructions to her son Stuart Macdonald about what to do with them after she died, even suggesting the notion of publishing an abridged version which she later started in 1930.29 As Elizabeth Waterston and Mary Rubio discuss, Montgomery was aware she was “creating in her journals a significant life history, a richly detailed social document.”30 Vappu Kannas describes at length Montgomery’s editing process, outlining four “timeframes” that play into how a reader might interpret the journals. The first is the actual lived events, the second is when Montgomery the author physically wrote these events, the third is when Montgomery edited and copied out these events into the ten volumes now located at the University of Guelph, reworking the journal into a fourth narrative.31 In addition to Montgomery’s original manuscript, the journals also exist as the Selected Journals, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, as well as the Complete Journals (the PEI Years edited by Rubio and Waterston; the Ontario Years edited by Jen Rubio)—although as of the time of writing this essay the Complete Journals only go up until 1933. As Suzanne L. Bunkers discusses in “Whose Diary Is It Anyway? Issues of Agency, Authorship, Ownership,” “Any diary that has been edited for publication, whether by a family member, an academic editor, a scholarly press, or a mass-market publishing house, bears the unmistakable marks of the editor(s) as well as the diarist.”32 For example, in the introduction of an updated The Complete Journals: The PEI Years, 1889–1900, Rubio and Waterston discuss how technology and changes in “reader attitudes” meant they could publish the journals “as Montgomery meant them to be published,” so that Montgomery’s adolescent years, that had previously been excluded in the Selected Journals, were now included.33 Therefore, the various versions, or timeframes, of the journal open up interesting questions as to the kind of narrative Montgomery wished to tell about her own life and how readers might interpret her journals as either the whole truth or a representation of what Montgomery wished to seem true about her life’s story.

Similarly, as Prose argues and as Frank’s multiple drafts attest, The Diary of a Young Girl is actually a “consciously crafted work of literature,” not just the “innocent and spontaneous outpourings of a teenager.”34 When Frank started revising her diary for what became The Diary of a Young Girl, she knew she was writing it for an external audience. According to Prose, on 29 May 1944, the Secret Annex residents gathered around the radio to listen to a Dutch news broadcast from London. The Minister of Education, Art and Science in the exiled Dutch government, Gerrit Bolkestein, sent out a call for “ordinary documents” that would help people understand what Holland had gone through during the war.35 When Frank heard this, she decided her diary would be an excellent contribution. Starting in the spring of 1944, Frank went back to the beginning and started Het Achterhuis [The Secret Annex]. When studied in English classes among works of fiction—and as Prose points out, the book is rarely studied in history classes—The Diary is usually explained as a version of the checkered covered book the author received for her thirteenth birthday in June 1942, “lightly edited” by Otto Frank (Anne’s father). But, in fact, that particular diary book was filled before the end of the year she received it. She next wrote in a red, grey, and tan cloth-covered book that spans 12 June to 5 December 1942.

Then the diary continues in an exercise book with a black cover, covering 22 December 1943 to 17 April 1944. The third exercise book begins on 17 April 1944 and ends three days before the residents of the Secret Annex were arrested on 4 August.36 There are two well-known published versions in English: the one commonly read, published in the 1950s, and a Definitive Edition edited by Pressler. But scholars can also study The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition, which contains three versions of the diary plus a 250-page report on its authenticity. Version “a” is the original draft, version “b” includes the revisions Frank made on loose papers, and version “c” is the one Otto Frank edited and published, which is a combination of the first two versions.37 In 2018, officials from the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam announced the discovery of two previously unknown pages of her diary.38 And, in 2019, the Anne Frank Fond published a 1000-page tome, Anne Frank: The Collected Works, providing an in-depth look at the multiple versions of the diary, as well as the author’s other writings.

This also means that when I first encountered Montgomery’s life-writing in the 1990s and The Diary of a Young Girl in 1982, I was not aware of the editorial input or the various versions of the manuscripts. Montgomery’s “selected” journals and Frank’s diary were the editions that most people—including me—had access to. Montgomery’s “selected” life-writing was my primary source until many years later when I was researching for my novel, Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery, and the first two editions of the Complete Journals had become available, providing me access to Montgomery’s editorial process (as mentioned above) and her life’s story in her own words. Conversely, Frank never got the opportunity to complete her story as she had intended because she was murdered. And, while she had hoped to turn her diary into a story that would show her experience hiding during the Second World War, other influences—such as her father’s and Pressler’s editorial work—as well as the multiple versions of the original manuscript mean that any version of the diary is a partial creative vision of what it could have been.

Writing as Sanctuary

As Stephanie Dowrick explores in Creative Journal Writing: The Art and Heart of Reflection, like many creative and artistic pursuits, journal writing can be important to one’s creative practice. Katherine Starr’s article “Journal Writing for Panic and Anxiety: A Write Way to Copy” also suggests that journal writing can help clear and calm the mind.39 Both Montgomery and Frank wrote about how writing helped them with their “moods.” Montgomery describes how it relieved stress during difficult periods, such as when her best friend and cousin Frede Campbell died.40 For example, on 17 August 1921 she writes, “This has been a miserable sort of day, so I’ve come to my journal to get it out of my system.”41 She feels so connected to the journal that destroying it would feel “like a sort of murder.”42 Interestingly, Frank also discusses how writing helps her to “shake off all of my cares. My sorrow disappears, my spirits are revived!”43 In a comment dated 28 September 1942 she tells Kitty what a source of “comfort” the diary has been and how happy she is that she “brought you [the diary] along!”44 And, on 2 January 1944, while rereading some of the older passages, Frank is somewhat shocked at what she had written about her mother. She defends herself by saying that she was suffering from “moods” and “hide[s] inside myself, thought of no one but myself and calmly wrote down all of my joy, sarcasm, and sorrow in my diary.”45 Therefore, both authors used journal writing as way to help with their mental health.

Inspired by these two writers, journalling has become an intricate part of my daily life, an essential tool in maintaining my mental and emotional stability. In the past, I would write to process the feelings of loss over bad breakups, when someone close to me died, or when I moved back to Toronto after living for seven years in Montreal. Like Montgomery and Frank, I also use my journal as a way to engage with books that I read. Frank appears almost immediately in my journals. On 12 October 1986, I write: “When I was reading her [Anne Frank’s] diary I realized that we are alot [sic] alike in some ways, we love to read, write, we hate math except I like algerbra [sic] and integers and we both like history. I think that we are different when she was popular and I’m not.” Upon subsequent rereadings, I now understand that my perception of Frank was not necessarily true. Frank might have appeared to be popular, but she did not feel like she had a true friend, which is why the diary is directed to “Kitty.”46 My teenage diary had a lot of the typical drama one might expect, but it also explored questions around faith and politics. However, I do not think I recognized how much Frank influenced my journal writing until the early 2000s, when I was revisiting some of my earlier books and going through a particularly difficult dark night of the soul. I recognized sections where I was possibly lying to myself, about, for example, a relationship I knew was over but pretended was fine—writing what I thought a diary should be versus what I needed to actually say. I recognized that I was copying what I had learned about diary writing from Frank and possibly others, not being authentic to my own style. Shortly thereafter, I dropped the diary’s name (“Special”), but I still see my journal as combining an address to an external fictional audience and the expression of an internal self. Still, Frank’s diary gave me a model of how a young person could write because she discussed a wide variety of topics—the same topics I was struggling with—and gave me permission to write about my life, even when I did not think I had anything interesting to write about.

Back in 1986, I wrote about rereading The Diary of a Young Girl because our junior high class was studying it, probably because Young People’s Theatre in Toronto was putting on a production of the play version adapted by Albert Hackett and Frances Goodrich. Perhaps as a way to avoid the trauma and images I associated with the Holocaust, on 4 November 1986 I write about seeing the play, particularly focusing on how much I love the actor who played Peter Van Daan because he was cute.47 But a review from Toronto’s NOW Magazine by Jon Kaplan provides more context for the theatrical production. Kaplan interviews Teresa Tova, the actor who plays Mrs. Van Daan. Tova discusses how she used her experience as a daughter of a Holocaust survivor to inform her role and the importance of reminding people that the Holocaust happened. She adds that the director’s choice of using words from the diary is an opportunity for Frank “to speak,” centralizing her voice for young people.48 This is an interesting detail because, according to Prose’s discussion of the play, the original playwrights, Hackett and Goodrich, do not use very much from the diary and make Frank look rather silly and immature.49 Perhaps hearing portions of Frank’s diary read out had a profound impact on my connection with the character and her diary. A number of years later, I read the diary again when the Definitive Edition was released. At that time, I write about being angry at Otto Frank for removing from the version published in the 1950s sections he believed were inappropriate, but I write that I was excited to read about Frank’s exploration of her sexuality because it was another way I could possibly connect with her.

I also write about returning to my comfort books from my childhood, including Anne of Green Gables. Perhaps this demonstrates my intuitive knowing of how necessary it was for me to dip back into comforting narratives. Interestingly, this is the first time I mention L.M. Montgomery or Anne of Green Gables in my journal, but it is not the first time I would have read them. While as an orphan Anne Shirley opens up to Marilla about her unstable upbringing before Green Gables, Montgomery does not spend a lot of time on Anne’s past, instead focusing on her immersion and transformation in Avonlea. I discuss going back to things I loved as a child, like watching the Anne miniseries and reading the books:

These Canadian stories are … wonderful ... They also make me remember the goodness. I think I became part of what I read as a child. Part of me that is romantic and wants to teach, who’ll rebel and stay herself no matter what … There’s not much hope today in the world. Maybe these books can give them something to hope for.

I am not sure who the “them” are, but it is clear that I was searching for purpose and clarity in my life, feeling discouraged about whatever was happening in the world, and looking to Montgomery for solace. Eventually, using Montgomery’s journals as a primary source for the first time, I wrote a university paper on her teaching years. In my journal, I comment on reading the whole Anne series again, focusing particularly on Anne’s teaching in Anne of Avonlea. Now, in retrospect, I suspect that my interest was also because I liked being in a world where someone was achieving something that echoed my own cherished goals of writing and teaching. While I know that many Montgomery readers turn to the Emily books because they are a portrait of a young woman author, for me, at this point in my life, I was more engaged with Anne Shirley because I was deeply invested in being a teacher and a writer, something that the character also wanted. I liked that there was a happily ever after—something Anne Frank did not have.

Working on my YA novel Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery for five years meant that I lived with Montgomery’s journals, letters, and scrapbooks. I had read her life-writing and fiction beforehand, but not in such a concentrated way. Part of my process is to physically inhabit my character in some way, so I took numerous trips to the places where Montgomery lived and that inspired her imagination and writing—Prince Edward Island, Saskatchewan, and Ontario—so I could embody Montgomery’s life. It was inspirational and joyful, and, while I worried a lot about crafting a novel that was worthy of the author I admired, I did not have to watch my creative and emotional boundaries the same way as I do when reading and working on Anne Frank. Working on Anne Frank means facing the images of genocide that I first saw when I was seven years old. It means facing the reality of anti-Semitism. It means confronting my people’s historical trauma. It is not joyful. But it is inspiring because I am moved to write for those who were silenced. Those like Anne Frank. I have yet to travel to the Anne Frank House as I have not had a lot of opportunities for European travel and have no desire to visit any Holocaust-related site. But it is the only one I would ever consider visiting. However, it would be a journey of remembrance, not of joyful inspiration.

At the end of Prose’s lecture at the S. Dillon Ripley Center on Tuesday 29 September 2009, an audience member asks, “What is was like to live with this material [Anne Frank’s diary]?” and Prose says:

I would make a kind of pact with myself. I would go for a week or maybe ten days without thinking here was this amazing girl, this genius murdered for no reason at all … And when reality would come back to me, I would have to quit working for a couple of days and do something else. And then I would think there’s a reason to go on and I would go back to the book … You can go a little while without thinking about a larger reality but it’s hard to go for very long.50

Trying to write this essay has been a lot like that. In exploring Frank’s writing, I can go deep into how she constructs a scene, examine her revision process, and even consider watching the various adaptations, such the miniseries starring Ben Kingsley (as Otto) and Hannah Taylor Gordon (as Anne) from 2001 and another one through the BBC from 2009. And while I pondered going back and watching them for this paper, I have not been able to do it because I do not want or need to watch Frank in a concentration camp, or the inevitable tragedy.

A ceiling fan. A shower tap. All these are reminders in one way or another of those photos I first saw when I was seven.

There is no need to remember. It is always there.

There is also a new Anne Frank’s Diary video released by the Anne Frank House, but I only watched the first few minutes. Maybe it is because the intended audience is teenagers or because it is, as Elly Belle wrote, that by creating and consuming media like this, “we minimize and flatten experiences like Anne’s into a digestible video series like this one, we do young people learning about tragedies like the Holocaust a great disservice.”51 Or maybe because there comes a moment when I cannot live with Frank’s work anymore, because the reality of her circumstances, why she was writing what she wrote, and why we only have fragments of what she could have been and could have written, is too overwhelming. While both Montgomery and Frank showed me models of how to use journal writing as a way to channel my anxiety, I intuitively turned to Montgomery and Anne Shirley for solace.

Montgomery and Frank as Mentor Texts

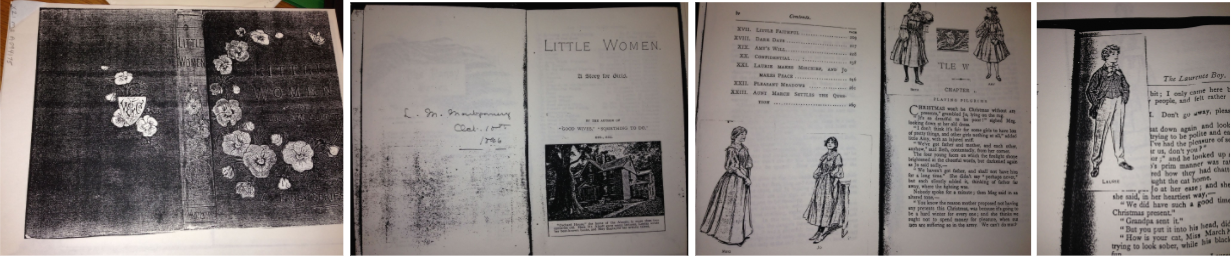

In Reading Like a Writer, Prose discusses how writers learn how to write by reading the work of their predecessors.52 For Prose, writers like Anne Frank and Shakespeare are “the teachers to whom I go, the authorities I consult, the models that still help to inspire me with the energy and courage it takes to sit down at a desk each day and resume the process of learning, anew, to write.”53 As this section will explore, Montgomery and Frank also followed this tradition by studying books to see how their favourite writers plotted scenes, created character, and constructed dialogue. Montgomery and Frank demonstrate how writers learn about craft by examining how the experts do it while also creating mentor texts themselves. Without a real mentor to guide her, Montgomery learned by studying the books in her home and that she had access to at school. As Rubio states in The Gift of Wings, Montgomery was influenced by a range of canonical English, Scottish, and American writers and some of the new Canadian writers in her schoolbooks, The Royal Readers.54 For example, the last line of Anne of Green Gables, (“‘God’s in his heaven, all’s right with the world,’”) is taken from Robert Browning; and some scholars (including yours truly) have made connections between Anne of Green Gables and the writing of one of Montgomery’s favourite authors, Louisa May Alcott, such as a comparison between Jo March in Little Women cutting her hair and Anne dyeing her hair green.55 And, when describing the books on her “plain little bookcase,” Montgomery notes how much she loved Alcott, having read and reread Little Women multiple times. In fact, Montgomery’s copy of Alcott’s novel (now located at the Guelph archives) is so badly worn that it can only be viewed as a photocopy.56

This image taken when I was conducting research shows how much Montgomery engaged with the book, glueing images of the characters and making notations in the margins. In her article, “L.M. Montgomery and Reading in/as Autobiography,” Emily Woster discusses Montgomery’s relationship to her reading as an opportunity for scholars to examine how Montgomery used books for introspection and self-construction. Woster states:

Many volumes contain markings, underlines, punctuation marks and arrows, annotations and commentary, pasted-in clippings that relate to the authors and subjects of the books, various cards and notes from friends, and other ephemera. A few books are so stuffed with clippings that their bindings have broken, and still others reveal repeated readings and reflections in their marginalia.57

Montgomery was therefore deeply invested in what she read.

Similarly, Frank discusses at length books which more than likely influenced how she approached writing. In her biography on Frank, Melissa Müller outlines many of the books the family read while they were in hiding, as Otto Frank was determined that Margot (Frank’s older sister) and Frank continue their education. While at first Frank was interested in what would be considered young adult literature, such as Eva’s Juegd (Eva’s Youth) by Dutch writer Nico van Suchtelen, eventually she was more intrigued by history and mythology.58 Encouraged by her father, from June 1943 to 2 July 1944, Frank kept The Favourite Quote Notebook and Egypt Book.59 Mostly made up of selected quotations by writers such as Goethe, Oscar Wilde, and Shakespeare, The Favourite Quote Notebook also contains phrases from Frank under the pseudonym “Rea.” Much as Montgomery engaged with her books, Frank’s Egypt Book is a combination of text and illustrations that she copied and cut from a book called Kunst in Beeld (Art in Pictures).60 Frank reflects on the texts she is studying or translating. She thinks that “Cissy van Marxveldt is a terrific writer” and likes the way Körner writes his plays.61 Eventually, Frank begins writing her own stories. On 7 August 1943, Frank writes about starting, “something I made up from beginning to end, and I’ve enjoyed it so much that the products of my pen are piling up.”62 According to the Anne Frank Fond, Frank copied these sketches from pieces of paper into a separate notebook and called it “‘Tales and Events from the Secret Annex described by Anne Frank,’ and bearing the comment: ‘inaugurated: Thursday, 2 September 1943.’”63 Other writings have also been discovered, such as a fantasy short story called “The Fairy” and her novel, Cady’s Life. Scholars have yet to make direct links between Frank’s reading and writing, but, as we will see in the next section examining the way Frank played with form, it is clear she was using these books as mentor texts.

Montgomery’s reflections while revising her journals also gave me a perspective on how she approached her life-writing. As Elizabeth Epperly describes in her introduction to the Ontario Years, 1918–1921, “In copying out those scenes … she [Montgomery] was intensely reliving her earlier life. Note this: she was reliving the scenes; she was fully experiencing them, not just intellectually acknowledging them.”64 For example, on 3 September 1919 when she wrote about transcribing the section about Sam Wyand’s field, Montgomery writes, “Instantly fancy took wing and I was back among scenes that have now vanished from the face of the earth.”65

It is also interesting to consider how I have had a relationship with both The Diary of a Young Girl and Anne of Green Gables, not necessarily consciously copying them, but writing about them in my journal and engaging with the books themselves, making notes in the margins and using sticky notes to mark favourite passages. They have become part of my autobiography, providing opportunities for self-examination and professional development, such as this essay and my novel.

Therefore, exploring how Montgomery and Frank revised their writing not only adds to how we understand their creative process but also provides an example for how writers can apply these strategies to their own work. When I was writing Maud, I read Montgomery’s books to get the flavour of her world and also to theorize how a teen Maud may have approached writing. I had the opportunity to look at the Rilla of Ingleside and Anne of Green Gables manuscripts when they were on display and made note of some of Montgomery’s revision techniques, such as her alphabetical/numbering system at the back of the manuscripts, where she would make notations on changes the typist would later add in. A number of Montgomery scholars have also pointed out the importance of examining her manuscripts for insight into the author and her life’s work. In “Approaching the Montgomery Manuscripts,” Epperly discusses this process whereby Montgomery would create a list of notes: “Note A was followed by Note B and eventually lead to Note Z. The alphabet started with A1 and moved through to Z1; from there, A2, lead to Z2, and so on.”66 So, for one of my revisions, I followed this technique, making a list of revisions as Montgomery had done. Now, mine has evolved into a system of lists by page numbers or chapters that I continue to use in my current work in progress—even in this essay. Studying how Montgomery revised helped me figure out a key piece of my own writing process, as I like having a list of corrections to refer back to. Even with the modern invention of copying and pasting, having a physical document to refer back to and keep track of the changes makes me feel like I have control over the form of what I am writing, particularly if I am working with something as big as a novel which has many moving parts. This technique also prevents me from getting too overwhelmed by the magnitude of an entire draft and allows me to hone in on a specific character or scene.

Other edited works, such as Elizabeth and Kate Waterston’s Readying Rilla: L.M. Montgomery’s Reworking of Rilla of Ingleside, Carolyn Strom Collins’s Anne of Green Gables: The Original Manuscript, and Benjamin Lefebvre and Andrea McKenzie’s edition of Rilla of Ingleside, are examples of scholarship that not only show Montgomery’s revision strategies but are also helpful for writers exploring craft. In a writing workshop, one might investigate how a particular scene or section of dialogue might evolve. As Waterston says, examining Rilla of Ingleside illustrates how “Each hand-written page also shows Montgomery’s scrupulous self-editing” and how the “Notes” added later provide more attention to character, dialogue, and description than in previous drafts. For example, as Waterston highlights, Montgomery’s “Note W” focuses on a nightmare Gertrude Oliver has of the Glen being swallowed up by water. This not only foreshadows Walter Blythe’s death and Jem’s capture but also highlights Gertrude Oliver’s character, “her irony, her unhappy love story, her wry mockery of the Blythes’ foibles.”67 Similarly, writers can see the importance of dialogue, character, and description in Collins’s discussion of Montgomery’s revision of Anne of Green Gables. In the original manuscript, Montgomery writes:

“There wasn’t any boy,” said Matthew wretchedly. “There was only her.”

“No boy! But there must have been a boy,” said Marilla.68

Then Montgomery inserts the following:

“There wasn’t any boy,” said Matthew wretchedly. “There was only her.”

He nodded at the child, remembering that he had never even asked her name.

“No boy! But there must have been a boy,” insisted Marilla.69

Montgomery’s “Note C2: He nodded at the child, remembering that he had never even asked her name” gives writers an example of how she added description as a way to create an emotional beat.70 That one line adds emotional depth by showing two things about Matthew: that he is so shy and shocked that he forgot to ask the child her name, and that he now feels “wretched” about it, displaying his sensitivity. There are also indications of Marilla’s character when she sees Anne and is (as the chapter heading says) surprised. Montgomery’s change from “said” to “insisted” illustrates Marilla’s confusion. Interestingly, this section is also an example of how writing sensibilities have shifted since the Victorian period. Most editors now would likely strike the poor adverb “wretchedly” and simplify Marilla’s dialogue tag to just “said,” as the emphasis on the word “must” would have been enough. With this one small section of dialogue writers can use Anne of Green Gables as a way to explore changing best practices in dialogue, character, and prose.

Examining Frank’s writing process can similarly provide writers with revision techniques. Frank’s decision to write Her Achterhuis provides her many opportunities for self-reflection and revision; the three available manuscripts mean that scholars can read Frank’s original “younger” voice and an “older” adolescent one. Prose suggests Frank was not “trying to fictionalize but rather to give the most accurate chronological record of the person she was and the person she became, and of everything and everyone that helped bring about that change.”71

This is evident in how Frank reflects on older entries, writing a comment with a date. For example, on 22 January 1944 Frank is reviewing an entry from 2 November 1942 in which she is sure she is going to get her period and adds: “I wouldn’t be able write that kind of thing anymore. Now that I’m rereading my diary after a year and a half, I’m surprised at my childish innocence.”72 Here, she is engaging with a younger version of herself and recording her development (even being embarrassed by it!), but she does not hide it from the reader, either. Frank’s description of her writing process, and of her anxiety and frustration when she cannot figure out a plot point or what her character is doing, mirrors the creative pitfalls most writers experience. The entry from 5 April 1944 contains some of the best examples of her passion for writing, her “gratitude” that God has “given me the gift, which I can use to develop myself and to express all that’s inside me!” But then she outlines some of the pieces she has been working on and is frustrated when she has not been able to work “out exactly what happens next” in her novel, Cady’s Life. She groans that it might all end up in the “wastepaper basket or the stove” but is renewed by some sense of determination.73 Frank is using her journal as a way to dialogue with herself about her creative and life questions and anxiety. Similarly, when I am writing anything—including this essay—I will often explore questions by journalling. For example, when I was working on my novel Maud and travelling across Canada, I would write about how thrilling it was to interview people about Montgomery’s life and about retracing her steps and feeling quite exalted. But not long after I might succumb to self-doubt or have to decide how (or if) some newly discovered piece of information might mean an entire rewrite and whether I was up to it, only to rally again. Frank models how journalling about writing can be a very therapeutic way to engage with and possibly exorcise creative doubts.

In a couple of entries, Frank also uses the diary as a way to play with elements of craft, such as dialogue, humour, or character. For example, Frank crafts a short scene called “The Best Little Table” based on a situation in the Secret Annex. According to the editors of The Collected Works, this is one of the sections that was written on a loose piece of paper and then transferred into the diary, appearing on 13 July 1944.74 Anne shares a room with Mr. Dussel—the dentist who comes to live with them—and he tends to spend much of his time in their room. With her father’s support, Anne asks Mr. Dussel if she could use the table in their room twice a week from 4:00 to 5:30 to study as she is finding it difficult in the afternoons because there is so much activity. He says no. When pushed further, Dussel insults Frank’s work—particularly what is suspected to be her Egypt Book—and refuses to budge. Upon consultation with her father, Frank tries once more but does not get anywhere. Eventually, Otto Frank has to get involved and Anne is given her space to do her work. Dussel, however, is so angry he does not speak to Anne for two days. Frank’s use of dialogue, humour, and character description helps build up the drama in this section: “So it seemed like a reasonable request, and I asked Dussel very politely. What do you think the learned gentleman’s reply was? ‘No.’ Just plain ‘No!’”75 In this sentence, Frank breaks the third wall by connecting with the reader and showing her sense of humour, while the pointed use of the word “learned” shows how upset the character “Anne” is over the situation. Later, Frank plays with point of view, referring to herself in the third person and then returning back to first: “The insulted Anne turned and pretended the learned doctor wasn’t there. I was seething with rage …”76 It is interesting to consider this change in point of view when thinking about the many “Annes” that Frank writes about and how she fictionalizes her experience. Here is “Writer Anne” using perspective to show how “Adult Anne” is controlling her emotions—and should therefore be taken seriously—when confronted with a man who does not. The “Adult Anne” turns and pretends that the doctor is not there, but the “I’s” heart is probably still pounding. However, with this line, “Anyone who is so petty and pedantic at the age of fifty-four was born that way and is never going to change,” “Writer Anne” gets the last word.

On an intuitive level, Montgomery and Frank’s exploration of others’ writing process helped to model for me how to approach writing, the writing life, and the writing process. Over the years I have gone back and reread my journal for projects, like this essay, or when I was looking for a particular detail about my life that I wanted to write about. And although I would never be prideful enough to think that my journals would be of interest to others, if I don’t burn them, I will have to eventually figure out what to do with them. Rereading my journal for this essay has taught me that they are a wonderful place to mine for stories. Still, I am not quite ready to revise them as Montgomery and Frank did. I continue to explore my life in the present, past, and plausible futures. My journal is my safe harbour. My sanctuary. While Frank gave me the model to work from when I started journal writing, Montgomery revealed for me how to dive back in and keep my journal writing going as a living, breathing document. Frank’s life story propels me with the idea that I have some kind of responsibility to tell my stories, for those who were never given the chance to tell theirs, for those who could not finish theirs. Montgomery and Anne Shirley provide me a model of storytelling. They show me how being in the creative process is just as important as the end product. And, that what survives might only be the beginning of a deeper understanding of the creative life.

About the Author: Melanie J. Fishbane holds an M.F.A. from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and an M.A. from Concordia University and teaches English and children’s literature in Toronto. With over seventeen years’ experience in children’s publishing, she also lectures internationally on children’s literature. She has essays published in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942 and Reconsidering Laura Ingalls Wilder: Little House and Beyond. Her YA novel, Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery, was shortlisted for the Vine Awards for the best in Canadian Jewish Literature. Melanie lives in Toronto with her partner and their furbabies, Merlin Cat and Angel Dog. She teaches at Humber College, George Brown College, and Seneca College. You can follow Melanie on Twitter @MelanieFishbane; on Instagram, melanie_fishbane; and like her on Facebook.

Banner image derived from an image featuring book covers of Anne of Green Gables, 1908. McGraw Hill Ryerson, 1968. Cover illustration by Hilton Hassell and Anne Frank: The Diary of a Young Girl, 1947. Simon and Schuster, 1958. Private collection, Melanie J. Fishbane, 2021.

- 1 Montgomery, AGG 191.

- 2 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 336.

- 3 Rosner, Survivor Café 34.

- 4 Rosner quoting and summarizing Yehuda, Survivor Café 35–38.

- 5 Robertson, Mele, and Tavernise, “11 Killed.”

- 6 Williamson, “In Germany.”

- 7 Schor, “Anti-Semitism.”

- 8 Montgomery, AGG 29.

- 9 Sullivan, Anne of Green Gables.

- 10 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 7.

- 11 Fishbane, unpublished journals, 4 and 5 April 1986.

- 12 Levitt, “No, Your Quarantine.”

- 13 Montgomery, AGG: Norton Critical 245.

- 14 Peter Van Pels (8 Nov. 1926 to 10 May 1945) was the son of Hermann and Auguste Van Pels, who hid with the Franks in the attic. Peter and Anne developed a close attachment until Anne started to lose interest and focused on her writing.

- 15 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 336.

- 16 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 242.

- 17 Darrow, Worlds within Worlds 16–17.

- 18 Pacheco, “L.M. Montgomery and Anne.”

- 19 Tousignant, “Anne of Green Gables.”

- 20 Waterston, Magic Island 9–10.

- 21 Montgomery, AP 57.

- 22 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 237; Blakemore, “How Anne’s Private Diary.”

- 23 Ozick, “Who Owns?”

- 24 Ozick.

- 25 Prose, Anne Frank 213.

- 26 Prose, Anne Frank 219–221.

- 27 Anne Frank’s Diary.

- 28 Franklin, “Anne Frank’s Diary.”

- 29 Rubio and Waterston, “Introduction” xxiv. And, as Vappu Kannas points out in “‘The Forlorn Heroine,’ any kind of comparison between the original and final versions is impossible because the original books no longer exist” (7).

- 30 Rubio and Waterston, “Introduction” xxiv, xxi.

- 31 Kannas 6–10.

- 32 Bunker, “Whose Diary Is It” 15.

- 33 Rubio and Waterston, CJ 1 x.

- 34 Prose, Anne Frank 5.

- 35 Prose, Anne Frank 11.

- 36 Prose, Anne Frank 10.

- 37 For a more detailed account, please see Blakemore, “How Anne’s Private Diary”; Prose, Anne Frank 9–10, 16–17; and Prose, “Publication History” 477–93.

- 38 Blakemore, “Hidden Pages.”

- 39 Star, “Journal Writing.”

- 40 Please see Fishbane, “‘My Pen’” 132. In this essay I explore how Montgomery used writing fiction to help deal with her grief over Frede’s death, the loss of her stillborn son, world politics, and her husband’s mental illness. In that paper I quote from Montgomery’s letters and journals about how she always used writing to help her when she was under emotional distress.

- 41 Montgomery, CJ 4 (17 Aug. 1921): 333.

- 42 Montgomery, CJ 5 (16 Apr. 1922): 25.

- 43 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 250.

- 44 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 1.

- 45 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 158.

- 46 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 6, 7.

- 47 Peter Van Daan is the fictional name for Peter Van Pels (8 Nov. 1926 to 10 May 1945). See https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/main-characters/peter-van-pels/; Francine Prose’s Anne Frank; Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl.

- 48 Kaplan, “Theatre.”

- 49 Prose, Anne Frank 216.

- 50 Prose, “History Bookshelf.”

- 51 Belle, “Anne Frank.”

- 52 Prose, Reading Like a Writer 2, 7.

- 53 Prose, Reading 12.

- 54 Rubio, Gift of Wings 42.

- 55 Montgomery, AGG: Norton Critical Edition 245. Please see MacLulich, “L.M. Montgomery and the Literary Heroine” 386–94, and Fishbane, “Brooding Boys and Loyal Lovers.”

- 56 Montgomery, CJ 1 (7 June 1900): 457.

- 57 Woster, “L.M. Montgomery and Reading” 200.

- 58 Müller, Anne Frank 193–97.

- 59 Frank, Collected Works 357–86, “The Favourite Quotes Notebook.” I had wondered if there was any chance Frank could have read Montgomery, that we could possibly see some kind of literary link, but there is no mention of the author in the diary. However, Anne of Green Gables was translated into Dutch in 1927, but it is hard to know if she had access to it, or if it was even available.

- 60 Frank, The Collected Works 389, “Egypt Book.”

- 61 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 56.

- 62 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 126.

- 63 Frank, Collected Works 211, Anne Frank Fonds “Introduction.”

- 64 Epperly, “Introduction” x.

- 65 Montgomery, CJ 4 (3 Sept. 1919): 180.

- 66 Epperly, “Approaching the Montgomery Manuscripts” 74.

- 67 Waterston and Waterston, Readying Rilla vi, x, 279.

- 68 Collins 45.

- 69 Collins 45; Montgomery, AGG 25.

- 70 Collins, Anne of Green Gables: The Original Manuscript 45.

- 71 Prose, Anne Frank 135.

- 72 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 60.

- 73 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 248–50.

- 74 Frank, Collected Works 211.

- 75 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 110–13.

- 76 Frank, Diary of a Young Girl 111.

Works Cited

The Diary of Anne Frank. 1980. “The Diary of Anne Frank (TV Movie 1980) Doris Roberts, Melissa Gilbert,” YouTube, uploaded by TrueTvMoviesChannel, 1 Feb. 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uSFfHkLiKY0.

Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation. By Anne Frank, adapted by Ari Folman, illustrated by David Polonsky, Pantheon Books, 2018.

Anne Frank Fond. “Introduction: Tales and Events from the Secret Annex.” Frank, Anne Frank: The Collected Works, pp. 211.

Anne of Green Gables.Fandom.com. Dutch Gallery, https://anneofgreengables.fandom.com/wiki/Gallery:Dutch.

“Peter van Pels.” Anne Frank House. AnneFrank.org. https://www.annefrank.org/en/anne-frank/main-characters/peter-van-pels/.

Belle, Elly. “Anne Frank Doesn’t Need to Be a Vlogger.” HeyAlma.com, 1 May 2020, https://www.heyalma.com/anne-frank-doesnt-need-to-be-a-vlogger/.

Blakemore, Erin. “Hidden Pages in Anne Frank’s Diary Deciphered After 75 Years.” History.com, 31 Aug. 2018, https://www.history.com/news/anne-frank-diary-hidden-pages-discovery.

---. “How Anne Frank’s Private Diary Became an International Sensation.” History.com, 31 July 2019, https://www.history.com/news/anne-frank-diary-symbol-holocaust. Accessed 1 Mar. 2020.

Bunkers, Suzanne, L. “Whose Diary Is It Anyway? Issues of Agency, Authority, Ownership.” a/b: Autobiography Studies, vol. 17, no. 1, 2001, pp. 11–27.

Darrow, Sharon. Worlds within Worlds: Writing and the Writing Life. Pudding Hill P, 2018.

Dowrick, Stephanie. Creative Journal Writing: The Art and Healing of Reflection. TarcherPerigee, 2009.

Epperly, Elizabeth R. “Approaching the Montgomery Manuscripts.” Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery, edited by Mary Henley Rubio, Canadian Children’s P, 1994, pp. 74–83.

---. “Introduction.” Montgomery, L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1918–1921, pp. v-xiii.

Fishbane, Melanie. “Brooding Boys and Loyal Lovers: The Development and Subversion of the Perfect Man Archetype in Young Adult Literature.” Master’s Thesis, Writing for Children and Young Adults, Vermont College of Fine Arts 2012.

---. Maud: A Novel Inspired by the Life of L.M. Montgomery. Penguin Random House Canada, 2017.

---. “‘My Pen Shall Heal, Not Hurt’: Writing as Therapy in Rilla of Ingleside and The Blythes Are Quoted,” L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley D. Clement, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015, pp. 131–44.

---. Unpublished journals, 1986 to 1999. Toronto.

Frank, Anne. Anne Frank: The Collected Works. Bloomsbury Continuum, 2019.

---. Anne Frank’s Tales from the Secret Annex. Translated by Michel Mo and Ralph Manheim, Doubleday, 1994.

---. The Diary of Anne Frank: The Critical Edition. Edited by David Barnouw and Gerrold Van Der Stroom, translated by Arnold J. Pomerans and B.M. Mooyart, Doubleday, 1989.

---. The Diary of a Young Girl: The Definitive Edition. Edited by Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler, translated by Susan Massotty, Doubleday, 1995.

Franklin, Ruth. “Anne Frank’s Diary, in Graphic Form, Reveals Its Humor.” NewYorkTimes.com, 9 Jan. 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/09/books/review/anne-franks-diary-in-graphic-form-reveals-its-humor.html. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Gritten, David. “Sweet Sixteen.” People Magazine, 24 Nov. 1980, https://people.com/archive/cover-story-sweet-16-vol-14-no-21/. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Kaplan, Jon. “Theatre: The Diary of Anne Frank Has a Note of Timelessness that Emphasizes Its Importance to a Young Audience.” NOW Magazine, 16 Oct. 1986, https://www.pressreader.com/canada/now-magazine/19861016/282218009260571. Accessed 4 May 2019.

Kannas, Vappu. “The Forlorn Heroine of a Terrible Sad Life Story: Romance in the Journals of L.M. Montgomery.” 2015. University of Helsinki, Ph.D. dissertation.

Kreuter, Aaron. You and Me, Belonging. Tightrope Books, 2018.

Levitt, Sophie. “No, Your Quarantine Is Not Comparable to Anne Frank: WTF Is Wrong with People on Twitter!” Alma, 7 Apr. 2020, https://www.heyalma.com/no-your-quarantine-is-not-comparable-to-anne-frank/. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Litster, Jennifer H. “The Scottish Context of L.M. Montgomery.” 2001. University of Edinburgh, Ph.D. dissertation

MacLulich, T.D, “L.M. Montgomery and the Literary Heroine,” Anne of Green Gables, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, W.W. Norton and Company, 2007, pp. 386–94.

Montgomery, L.M. The Alpine Path. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1997.

---. Anne of Green Gables. Tundra Books, 1908.

---. Anne of Green Gables: A Norton Critical Edition. Edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, W.W. Norton, 2007.

---. Anne of Green Gables: The Original Manuscript. Edited by Carolyn Strom Collins, Nimbus Publishing, 2019.

---. Anne van het Groene Huis. Translated by Betsy de Vries, H.D. Tjeenk Willink and Zoon, 1927. Worldcat, https://www.worldcat.org/title/anne-van-het-groene-huis/oclc/902646179.

---. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, Oxford UP, 2012–2017. 2 vols.

---. L.M. Montgomery's Complete Journals: The Ontario Years. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills P, 2016–2019. 5 vols.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985–2004. 5 vols.

Müller , Melissa. Anne Frank: The Biography. Metropolitan Books, 1998.

Ozick, Cynthia. “Who Owns Anne Frank?” The New Yorker, 29 Sept. 1997, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1997/10/06/who-owns-anne-frank.

Pacheco, Adriana. “L.M. Montgomery and Anne: A Parallel Life.” AnneofGreenGables.com, https://www.anneofgreengables.com/blog-posts/l-m-montgomery-and-anne-a-parallel-life. Accessed 8 May 2021.

Prose, Francine. Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife. Harper Collins, 2010.

---. “History Bookshelf: Anne Frank: The Book, the Life, the Afterlife.” C-Span, 9 Sept. 2009, https://www.c-span.org/video/?289227-1/anne-frank-book-life-afterlife.

---. Reading Like a Writer: A Guide for People Who Love Books and for Those Who Want to Write Them. Harper Perennial, 2006.

---. “The Publication History of Anne Frank’s Diary.” Frank, Anne Frank: The Collected Works, pp. 477–93.

Robertson, Campbell, Christopher Mele, and Sabrina Tavernise. “11 Killed in Synagogue Massacre; Suspect Charged with 29 Counts.” New York Times, 27 Oct. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/27/us/active-shooter-pittsburgh-synagogue-shooting.html.

Rosner, Elizabeth. Survivor Café: The Legacy of Trauma and the Labyrinth of Memory. Counterpoint, 2017.

Rubio, Mary. “‘A Dusting Off’: An Anecdotal Account of Editing the L.M. Montgomery Journals.” Working in Women’s Archives: Researching Women’s Private Literature and Archival Documents, edited by Helen M. Buss. and Marlene Kadar, Wilfred Laurier UP 2001, pp. 51–78.

---. L.M. Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Doubleday, 2008.

Rubio, Mary Henley, and Elizabeth Waterston. “Introduction.” Montgomery, The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery: Vol 1: 1889–1910, pp. xiii-xxiv.

---. “Introduction.” Montgomery, The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889–1910, pp. ix-xi.

Schor, Elana. “Anti-Semitism Seen in U.S. Capitol Insurrection Raises Alarms.” CTVnews.ca, 13 Jan. 2021, https://www.ctvnews.ca/world/anti-semitism-seen-in-u-s-capitol-insurrection-raises-alarms-1.5265247.

Star, Katherina. “Journal Writing as a Tool for Coping with Panic and Anxiety.” Verywellmind.com, https://www.verywellmind.com/journal-writing-2584072.

Sullivan, Kevin, director. Anne of Green Gables. A Kevin Sullivan Production, 1985.

Tousignant, Marylou. “Anne of Green Gables Is Very Much Alive in Canada.” Washington Post, 27 Aug. 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/kidspost/anne-of-green-gables-comes-to-life-in-canada/2018/08/27/9d2eff42-a0a3-11e8-8e87-c869fe70a721_story.html.

Waterston, Elizabeth. “Reflection Piece: The Poetry of L.M. Montgomery.” L.M. Montgomery and Canadian Culture, edited by Irene Gammel and Elizabeth Epperly, U of Toronto P, 1999, pp. 77–84.

---. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery. Oxford UP, 2008.

Waterston, Kate, and Elizabeth Waterston, editors. Readying Rilla: L.M. Montgomery's Reworking of Rilla of Ingleside. Rock’s Mills P, 2016.

Williamson, Hugh. “In Germany, Anti-Semitism Creeps into Covid-19 Protests: Attacks Against Jews, Jewish Institutions Rose 13 Percent Last Year.” Human Rights Watch, 19 May 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/19/germany-anti-semitism-creeps-covid-19-protests.

Woster, Emily. “L.M. Montgomery and Reading in/as Autobiography.” a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, vol. 29 no. 2, 2001, pp. 199–210.