In 2002, when I was sixteen, my bedroom walls were covered with photocopied excerpts of Anne’s words.

I had surreptitiously used the school library’s photocopier to create this (non-study-related) contraband, copying page after page from my Anne books. It was at this same school library’s second-hand book sale that I’d discovered Anne in the first place.

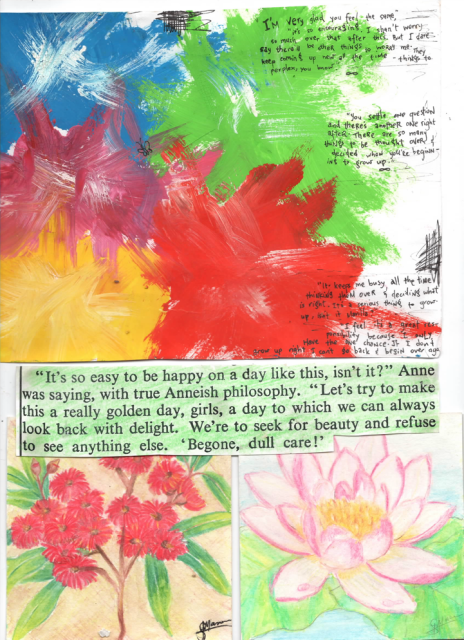

Young Anne became a companion to my high-school self. Her words gave me hope. “Everything that’s worth having is some trouble,” she counselled (Montgomery, AA, ch. IX), as I struggled through those complex years. I was afraid of failure, like most of my peers; Anne was a model of buoyant resilience, unafraid to confess her mistakes.

At twenty, I was married. I moved out of my parents’ house. For the previous few years, my home life had been tumultuous and deeply traumatizing. But I had held myself together. In the new (but entirely unfamiliar) space of marriage, it all came crashing down …

and I reached for Anne. I knew I would find solace and comfort; that nothing in Anne would frighten me or add to my distress. She gave me a holding space. She directed me toward hope and possibility, helping me to hold on amid the destruction and anguish. I searched with Anne hungrily for home.

When I was twenty-two, my first daughter was born. This new horizon of meaning and purpose felt like the revelation of a shimmering fourth dimension in life. And yet I was also thrown into chaos again. The sleep deprivation! The frustration of purpose! The incessant needs! The physicality! (I was very poor at asking for help; I did not want to bother anybody. And I was afraid to relinquish control.)

I would lie on the bed, feeding my daughter to sleep. She would appear to have dropped off … I would gingerly prise my nipple from her occasionally quivering lips … I would extract myself from the bed as quietly as I could and …

WAHHHH!

Every. Time.

She was so sensitive to my absence you’d think her life depended on my presence. In many ways, it did. And that terrified me. I felt inadequate, trapped.

What could I do while lying beside my dozing child, my presence keeping her at rest? I became riled with frustration; I was a hostage. My chest would constrict as my one hour of daily freedom slipped away. But then, one day … epiphany struck. A turning point! Anne kept me company while my baby slept! She brought me joy and dispelled vexation. I read about Anne having, and losing, her own babies. I held mine closer.

When I was twenty-five, my second daughter arrived. Immobilized by tiredness, I decided we would try audiobooks at bedtime. So began the addiction (now shared by all three of us). And who did I turn to in those days of exhaustion squared, when my eyes weren’t open, but my ears certainly were? I don’t need to spell it out (though if I did, it would end with an “e”).

I would lie in the dark as peace gently descended, kept company by Anne, Gilbert, and Captain Jim, as friendships were woven, and the complexities and poignancy of adult life replaced the guileless enthusiasm and vulnerability of youth. Stories of Anne wove themselves into my children’s minds, snatches of sense amid comforting sounds, like waves washing onto the shore.

There is a heuristic drive within Anne—a hunger—that is very familiar to me. I suspect it reflects an aspect of Montgomery herself, the lonely young girl who found solace in the imaginary worlds of a burgeoning writer. How else could she have written this into Anne herself with such poignancy, such intimacy? She knew. It is good for artists and writers and thinkers—for imaginers and dreamers—to feel that they belong. So often these pursuits can represent a certain solitude of the mind, even a sense of displacement—and certainly a desire to be heard. In my own writing, performance, and relationships, I want to give the world what Montgomery has given me—a sense of belonging. Solidarity. Comfort. Kindred spirits.

I’ve grown up alongside Anne, and our journey together continues. Anne has helped me find myself—to make myself. She will always be part of me.

Bio: I am a writer from Melbourne, Australia. I am also a final year Ph.D. student in the philosophy of religion, and I work as a research officer with the Young and Resilient Research Centre at Western Sydney University. For me, academia is as much a passionate creative outlet as my works of fiction and exploratory articles. I am also a performer, actor, and interpreter of text—I have produced and narrated many audiobooks and have performed in full-cast audio plays, including The Secret Garden (as Dickon), Oliver Twist (as Oliver,) and Rilla of Ingleside (as Anne—the joy!). Gardening keeps me grounded. I’m interested in more than I have time to pursue, and it’s possible that ink runs through my veins—though I’m anything but blue-blooded. Read more at my website, www.sarahbacaller.com.

Work Cited

Montgomery, L.M. Anne of Avonlea. 1909. Project Gutenberg, 1992, updated 2021, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/47/47-h/47-h.htm. Accessed 14 April 2024.