Waiting without impatience or expectation. The traveller should arrive before supper. An answer may come by week’s end.

To revisit L.M. Montgomery’s stories and letters is to recall that human nature was once closer to bird- or chipmunk- or flower-nature. There was no rushing of Nature’s order that has now become second nature to us: expediency at any cost … even free.

So often, her stories pivot around matters of trust and proof and will. The need to persevere, prove one’s worth, commit to industriousness, eschew tomfoolery. (How do we even define the latter these days?)

Ardour. In her simple story, “The Fillmore Elderberries,” there’s a task I recognize from the acres in the Appalachian foothills where I live. For a modest payment, a young boy named Ellis commits to the prodigious task of ridding his Uncle Timothy’s field of elderberries, and, upon prevailing, earns his trust and even sponsorship: “… if I find you always as industrious and reliable as you've proved yourself to be negotiating them elders, I’ll most likely forget that you ain’t my own son some of these days” (302). This is the last sentence of the story.

* * *

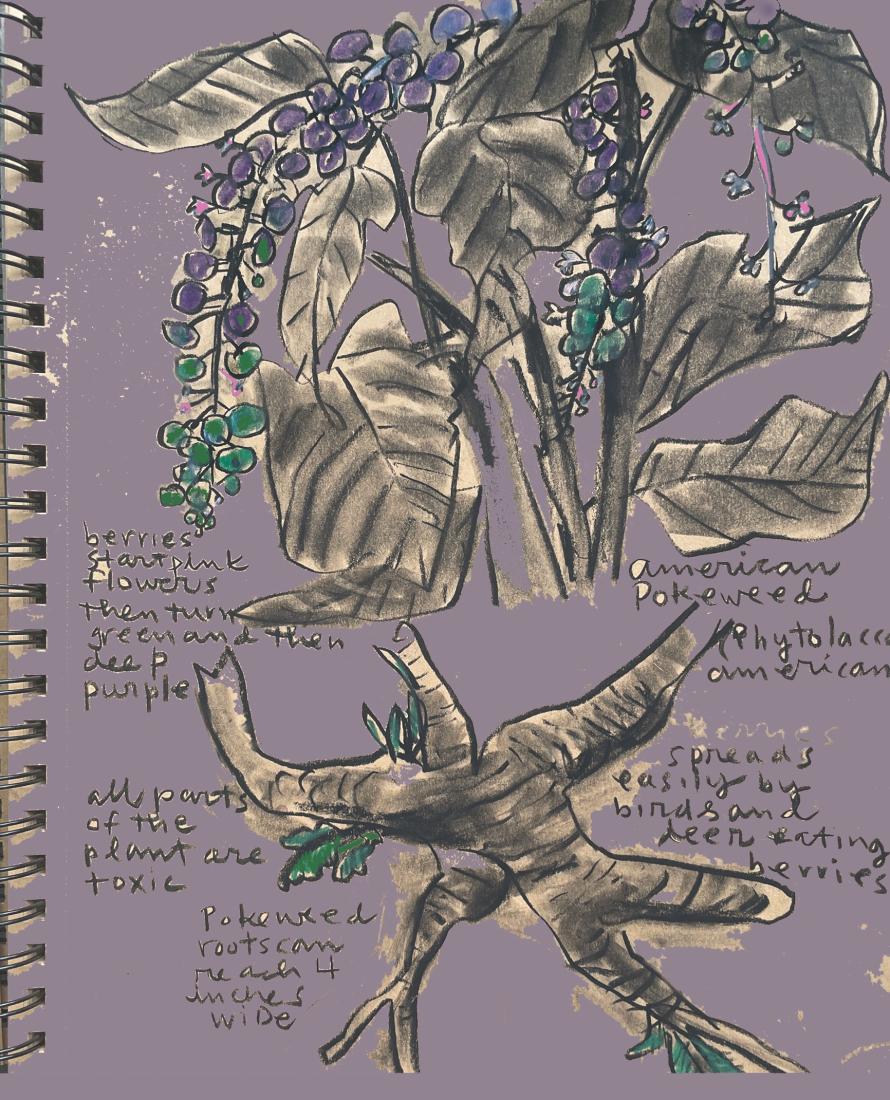

When a hundred-year-old black-cherry tree uproots here, revealing its Medusa head of shallow roots, pokeberries occupy the tree’s previous understory the following year. It’s an open invitation. As in the Bible, each felling begets generations. Mockingbirds, northern cardinals, catbirds—many creatures relish the pokeberry’s copious fruit. The plant’s hollow, straw-coloured stalks deteriorate over winter like the bones of a scarecrow becoming more and more enfeebled. Come spring, a new plant thrusts upward from the deep, fleshy taproot and overtakes the old skeleton.

I’ve failed to provide the necessary effort to eradicate them. A matter of priorities. A lack of ardour. Distractions. The tomfoolery of my life and health. Digging up those taproots is an ordeal that the story “The Fillmore Elderberries” sets forth as a test of resolve, of conviction, of confidence for a young man. Ellis laboured with “vim and vigour”: “The elderberries tried to hold out … but they were no match for the lad’s perseverance” (302).

While elderberry can grow into a thicket, its roots are shallow and comparatively easy to pull. They’re not the noxious invasive that is the pokeberry, inkberry, inkweed, pokeweed. My guess is that Montgomery meant pokeberry. They suit the terrain in the story. They are considered a nuisance weed, capable of spreading by seed quickly—particularly along fencerows and in open meadows. All parts are poisonous. And their taproots can be over a foot long and four inches thick. Their only use: dye and ink.

Civil War letters from the South were sometimes penned with turkey quills and “poke ink.” Historians suggest Walt Whitman, while volunteering close to the battlefield, wrote his letters in this ink (Gilmer).

* * *

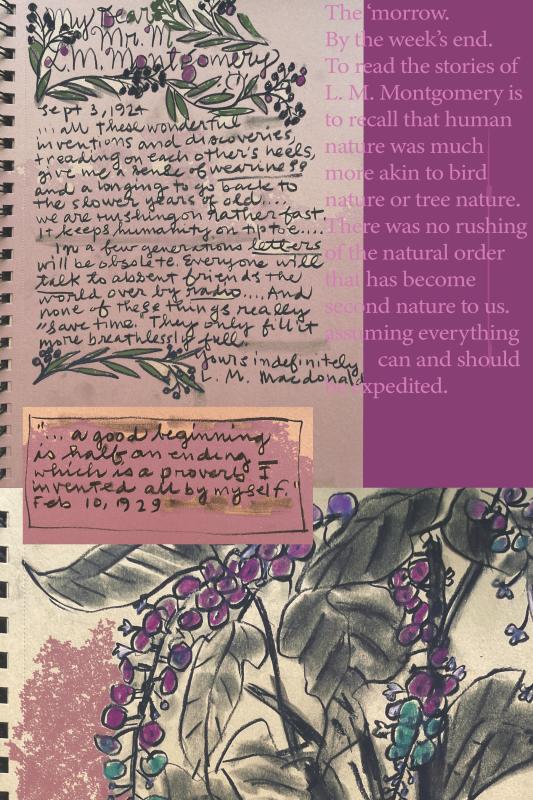

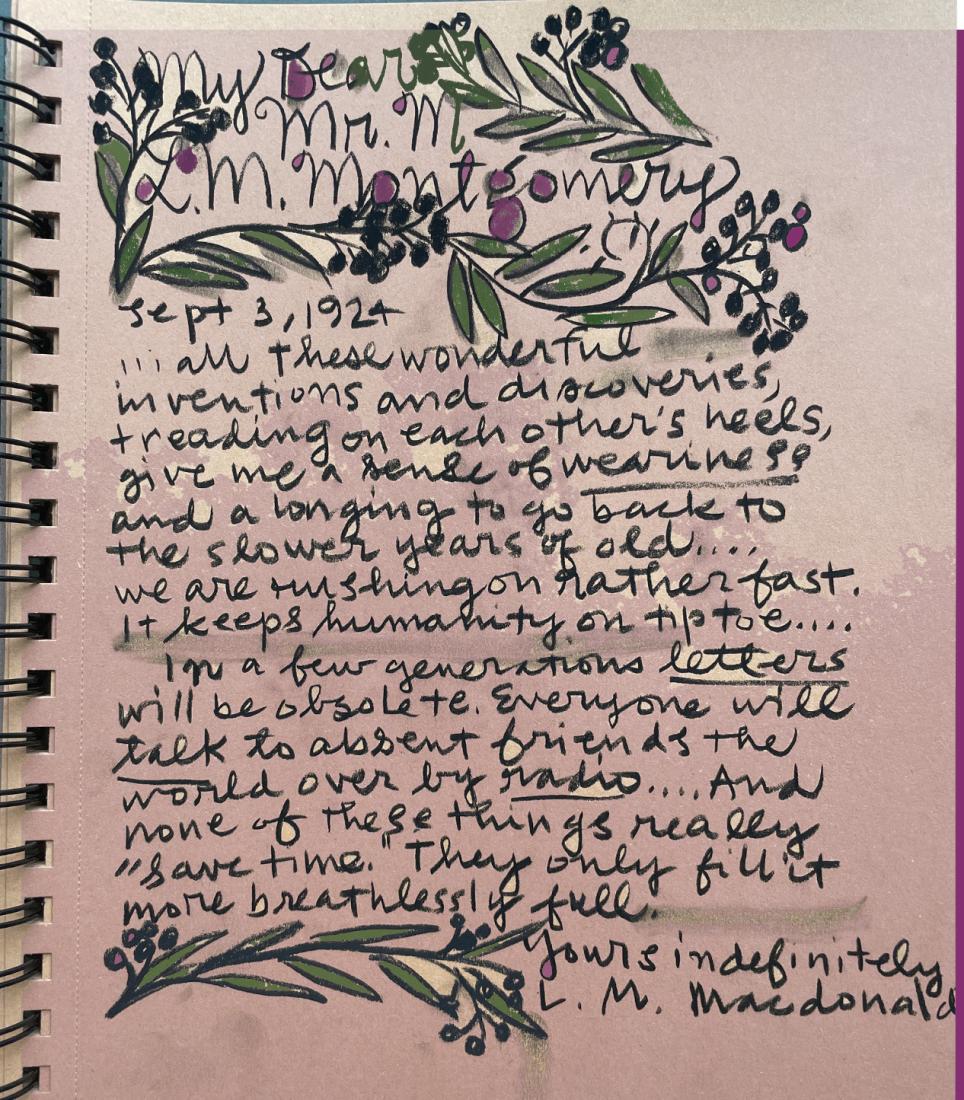

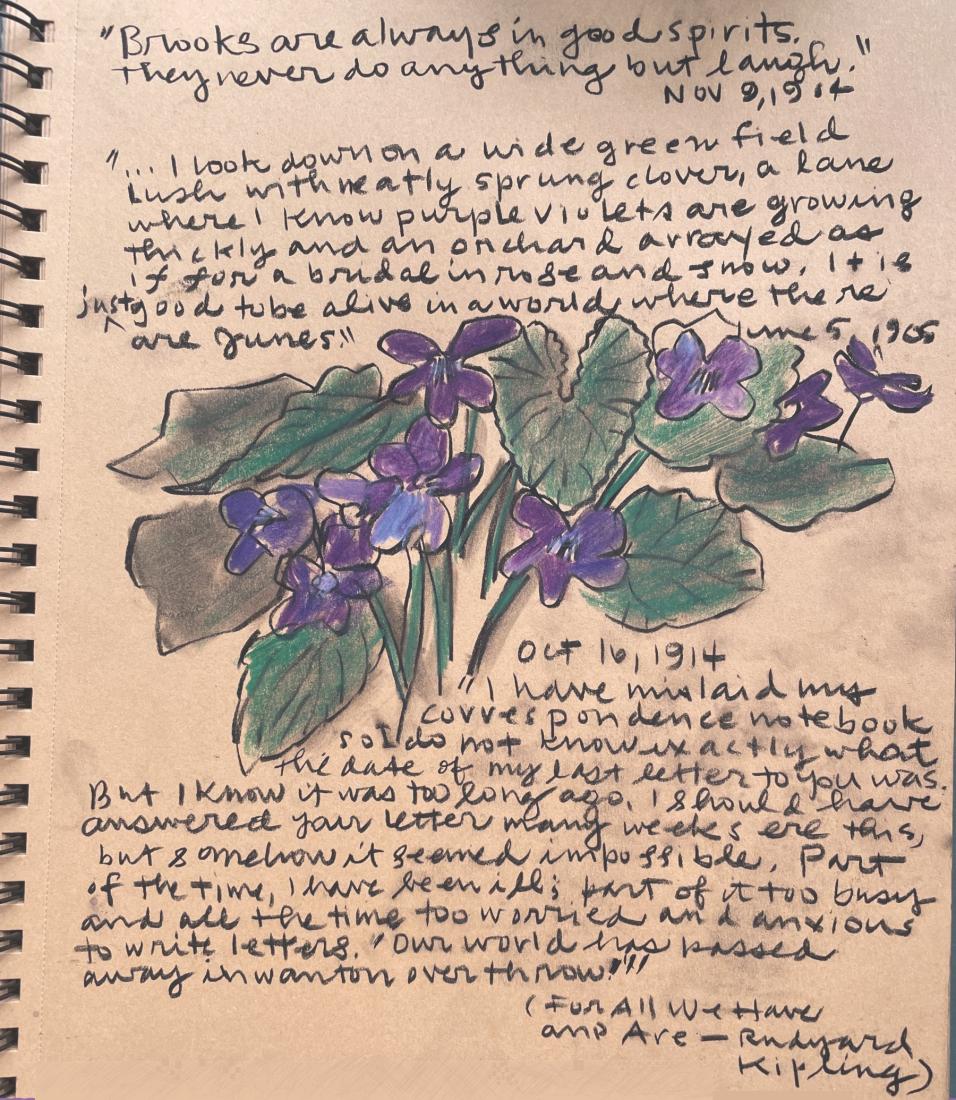

In Montgomery’s letters, as in those of so many authors of this and even the present era, there is a steady refrain of apology: the unintentional and yet predictable delay in reply. There’s an implied request for forgiveness because the present letter wasn’t sent as quickly and thoughtfully and attentively and charmingly as intended.1

Reading the letters of Montgomery to George Boyd MacMillan, a correspondence that spanned decades, there is a refrain of gratitude for receiving the latest letters, as well as the eagerness for the next: a Möbius strip, a continuous looping without start or finish.

But the underlying current of their letters is more of an undertow: how to keep up. How to make the time to compose a letter of what has recently passed, rather than dash off or patch together something bland. The busy “hustling,” as she called it, of neglecting her reading, keeping up with reviews and contracts, beginning new works, revising or revisiting others—it all had to fit in the motley composition (composting?) of a day. Her letters’ would-be narratives are often reduced to a concatenation of topic sentences. Living a life and reporting it—the two vie for attention.

* * *

My home is a collage. Life is—as I see it. Experiences and memories and relationships are culled from the continuum, and collected. We collect ourselves. Montgomery herself maintained a variety of scrapbooks and illustrated notebooks.

A quotation, variously attributed to Albert Einstein, reads: “time was invented so everything doesn’t happen at once.” Literature revels in this, reveals the narrative that escapes us. It sifts and re-presents, sequences and reflects. The speed of life exceeds our capacity to enjoy and even endure it. Literature helps to compose us. Help us, yes, collect ourselves. Montgomery had an exquisite sense of this. An awareness of the accelerating haste and futility of contrivances and “time-savers.”

Now we attempt to survive in a time when even haste cannot be wasted. Likes, yelps, thumbs, hearts, texts, comments: they stand in like IOUs and doorstops. Well-meaning, but rather meaningless. They’re the go-to, got-to, get-it-done means of response. We have no delays in our communication. Little reason to pine for a reply. (It’s difficult not to feel the quaintness expressed in Montgomery’s urgency.)

Ever-present in the Victorian novels I’ve enjoyed over the years are those invitations and replies hand-delivered by messengers. A reply might be returned later in the day. Each missive is penned in ink and sealed with wax. Such dutifulness, deliberateness, intentionality.

In my childhood, the mail came twice daily.

At the start of my writing career, my communications were typed in duplicate with carbon paper, and sent with US postage—the most urgent, by priority mail. Long-distance phone calls were costly and carefully considered.

Along came FedEx and priority deliveries, and manuscripts with Post-its and pencilled comments that required a second coloured pencil for responses. All of this strained and foreshortened the necessary time to think and rethink, consider and reconsider. Deadlines shifted from weeks to days.

And here we are today, writing or texting and researching with the aid of spellcheck and AI and Google. No visits to the library’s microfiche or the card catalogue. No waiting for interlibrary loans or for a photocopier to accept your fistfuls of dimes in order to glide across the platen at the rate of three pages per minute. Now, the expectation is that electronic files will arrive instantly, and they can return quickly with comment bubbles and a spider’s web of accept/reject changes … as if time were hemorrhaging, and we had to stitch and staunch it with the fastest means possible.

Literature has always forced us—willingly or not—to take our time. Our eyes can only scan so quickly across the page. Our brains can only convey so much information along the fire-brigade of synapses in our brains. The closure of one of Montgomery’s letters to Mr. MacMillan was, “Indefinitely yours” (122). I find that sense of commitment and continuity so inspiring. Let’s take time, rather than give it up. Let’s dig up pokeberries—or elderberries—just for the ink of ardour.

Bio: Michael J. Rosen has written, edited, or illustrated some 150 books for readers of all ages. He also works as painter, printmaker, collage-artist, and ceramicist. For twenty years, he served as literary director of the James Thurber House and edited seven books of the author/cartoonist’s uncollected work. The author of five books of poetry, he shares a hundred acres in the foothills of the Appalachians. www.michaeljrosen.com

- 1 For example, see Montgomery, L.M. “Letter to Sylvia.” 25 March 1935. L.M. Montgomery Institute-Ryrie Campbell Collection, https://kindredspaces.ca/islandora/object/lmmi%3A17148#page/1/mode/1up.

Works Cited

Gilmer, Maureen. “Poke Plant an Unsung War Hero.” The Atlanta Journal Constitution, 17 July 2016. https://www.ajc.com/lifestyles/home--garden/poke-plant-unsung-war-hero/ozy2UMz21YoTQ5dH9PWfKL/.

Montgomery, L.M. “The Fillmore Elderberries.” East and West, 18 September 1909, collected by Rea Wilmshurst.

---. My Dear Mr. M: Letters to G.B. MacMillan. Edited by Francis W.P. Bolger and Elizabeth R. Epperly, Oxford UP, 1992.