This article explores my encounter with Anne of Green Gables as an adolescent living in a coastal city in Southeast China. The character of Anne was a unique addition to my childhood repertoire of favourite heroines, as I gradually began getting to know the imaginative girl, first by reading the translations and then the original, unabridged versions. My private journey of reading the Anne books offers a lens through which to observe the publication, adaptation, and reception of L.M. Montgomery’s most famous work in China.

In the summer of 2005, banyan trees were flourishing in the small coastal city in Southeast China where I spent my childhood. The thick leaves and sprouting branches formed huge canopies, and the air smelled of sweat, lollipops, and fresh canes. Having just crossed the threshold from childhood to adolescence, I sashayed across the asphalt boulevards outside the lab building where my father worked, my chest bursting with aspirations for ambitious holiday reading. That was the summer I encountered L.M Montgomery’s Anne.

In his foreword to Red-Haired Anne, a Chinese version of Anne’s story published by Tsinghua University Press in 2012, scholar and translator Yao Yao compares Anne with two other famous girl characters in Chinese classic literature: Lin Daiyu from the eighteenth-century novel A Dream of Red Mansions by Cao Xueqin, and the brave girl general Mulan of the famed Chinese poem “The Ballad of Mulan” (originally published around 400 CE). Coincidentally, these girls happened to be my favourite characters since childhood. Daiyu is the demure one—an intellectually distinguished, sensitive, and inquisitive girl poet navigating the complexities of life in a feudal family and a frail girlhood shadowed by illness and loneliness; Mulan is the dashing heroine assuming the disguise of a man to fight for her father in the war.

But Anne is different from any of those Chinese heroines about whom I had—or have since—read. Her feisty personality and chattering optimism opened up another possibility of girlhood for me, one that aligned hauntingly closely with my early adolescent experience in China. The summer I read Anne of Green Gables, I had begun dreaming about my future. At that time, I was living in a research institute where my father worked as a chemist. It was a compound filled with academics and scientists, but I did not feel that I belonged to the world of science. In Anne I found a kindred companion: we both had aspirations for literature, and both of us wanted to teach. At a time when Chinese parents and schools emphasized science over the humanities, and while my classmates took advanced math lessons, I passionately empathized with Anne’s storyteller sensibility and imaginative excursions, making myself a guest in her house of dreams.

While my interest in Daiyu and Mulan derived from cultural familiarity, my acquaintance with Anne began as a process of decoding. Having just started learning English, I waded through the original English version with a dictionary, stumbling repeatedly over Anne’s linguistic flourishes. I therefore resorted to the translations as a “mediator” between Anne and me. While some of the earliest Chinese translations of Anne date back to the 1930s, the version I found was conceived much later, in the late 1980s, by Ma Ainong, who went on to gain considerable fame and recognition as the translator of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone in 2000.

Anne of Green Gables was Ma’s debut work of translation. In 1986, Ma came across the book and fell in love with it immediately. With the mentorship of her grandfather, then a renowned translator and editor at the Commercial Press (the first modern publishing body in China), Ma set to work on the translation, which was published in 1987. Her translated version was bound neatly as part of the American School Student Extended Reading List Series compiled by People’s Literature Publishing Press. Following the publication success of Ma’s translation, Anne became a signature piece in the children’s section of Chinese bookstores, leading to many reprints of her translations. Many more translated versions of Anne by multiple publishers and translators soon followed. While Ma adopted a literal translation of the title, two other popular translations were Red-Haired Anne by Yao Yao (2012) and Fine Lady by Zeng Xiaowen (published in Taiwan, 2019).

Yet it was Ma’s translated version, among the earliest print versions of her translated work, that landed in my hands eighteen years after its initial publication.

The book bore the original, refreshing voice of a rising translator before edits and adjustments were made in the reprinted versions of the later translations.

As an apprentice reader of foreign classics, I was often confused by names, places, and dialogue that seemed quite at odds with straightforward Chinese vernacular. Yet Ma’s translation offered a different reading experience than what I was used to: it did not carry the obtuse rhetoric of a translated work nor the droning voice of a pedagogue. Instead, Ma replicated the tone and spirit of Montgomery’s prose, particularly the vivacity of Anne’s monologues. Anne’s ingenious naming of the lanes, lakes, and fields around Green Gables opened a world of beauties that I could connect with without leaving my room. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Anne was on the curriculum reading list for Chinese primary- and middle-school students, but it was different from any other classic I had read on that list. Anne’s story was light and heartwarming; it did not, for me, bear the weight of a hefty masterpiece to be digested with hours of poring over lofty syntax and intricate passages.

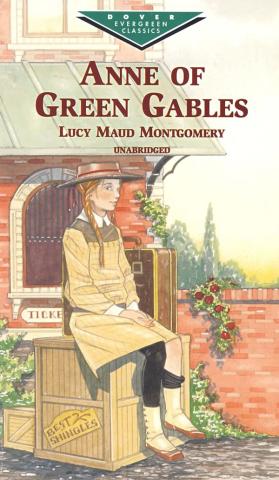

When I first encountered Anne, I was about to start middle school, and reading the book coincided with my journey of learning English as a second language. Therefore, a year after I had devoured Ma’s translations, I decided to go back and read the original novel (an unabridged version by Dover Evergreen Classics) all over again.

Anne’s devotion to language became an ideal entry point for me: I studied her descriptions, parsing her “long-winded” monologues and memorizing them word for word. I managed to replicate Anne’s imaginative detours, grafting her grand descriptions into my own English compositions, glibly overlooking the requirements of style and accuracy. More than anything else, I wanted to write as Anne does, and not just write but write in the language that Anne speaks. Phrases like “alabaster brow” started popping up in my own writings, including my composition exercises for school. Unsurprisingly, my English teacher decided that my writings did not align with the requirements of standard composition and reprimanded me for my flowery rhetoric. At the time, second-language teaching in China very much followed a strict pattern, prioritizing skill, grammar, and clarity over creativity. To continue writing as imaginatively as Anne, I established a parallel writing life at home. Despite my insufficient mastery of the English language, I started writing poetry in English. Stories soon followed. Anne’s ability to reinvent and reshape the stories she read also inspired my earliest attempts at what is known as “writing from sources.” Needless to say, my writings were poor imitations and unembellished artifacts, but they nevertheless became the starting point for me to write in a second language.

Apart from enlivening the processes of my early development as a reader and writer, Anne also held a unique emotional appeal. Despite the differences in space, time, and geographic location, Anne’s humble beginnings as an orphan and her later attempts at finding family and friendship resonated with the loneliness I had felt as an only child growing up under China’s one-child policy. As an awkward teen, I clung to my childhood habits of talking to myself and play-acting, habits that I was too ashamed to admit to my parents and peers. Reading Anne, however, validated my secret inclinations. In Anne I saw with clarity where imagination can take us. Like Anne, I embraced the value of talk, whether it was directed at adults (sympathetic or otherwise), at friends, at objects, or at myself. Through talking, the mind frees itself from the strictures of the rules that hold us back from creative thinking and imaginative transcendence. Indeed, when it comes to the red-haired heroine, scholars and translators have unanimously touched upon the intensity of her imagination. For Ma Ainong, Anne’s imagination was “the catalyst for her moral and intellectual development, an impetus for the realization of her ideals.”1 For Hans Christian Andersen–award winner Cao Wenxuan, Anne’s imagination is poetic, and “a poetic life is no doubt life of the highest degree.”2 I too credit Anne’s imagination as a positive example for my own interior growth, a road map that teaches me the importance of living our lives to the fullest.

To be sure, Chinese literary critics and literacy advocates have always praised Anne for her kind heart, liveliness, and tenacious spirit despite her humble beginnings. As Yao Yao asserts:

The magic world has nothing to do with Anne. Anne is just an ordinary girl, like you or your girl friends … She doesn’t have the most breathtaking beauty, but she can move you with her sincere words; she was an orphan, but she seldom complains … she has her share of faults … but her exceptional imagination enables her to transform the bitter realities into the brightest hopes for the future.3

Notably, Anne’s “ordinary” features, much like those of Jane Eyre, have been mentioned by others. Ma describes Anne’s story as one of “an ugly duckling turning into a swan.”4

Chinese author Zhou Guoping observes that Anne brings hope to readers because “she has already gained half the happiness just by hoping for the best.”5 Interestingly, Anne’s laudable traits have proven to be a powerful pedagogical vehicle and source of affective engagement for a particular group of Chinese youths. Yao, for instance, pinpoints the usefulness of Anne’s story for the post-1980s and post-1990s generations in China. Young people of both generations experienced China’s profound economic boom since the first half of the twentieth century, as their lives became increasingly shaped by a competitive neoliberal market economy. Other pressures included the steady rise in housing prices and the increase in city population as young people left the countryside to seek upward mobility in big cities. Yao argues that Anne’s optimism was an emblem of hope for these youths, many of whom were inspired by her sense of humour and resilience even as she encounters adversarial conditions.6 The ability to turn a bad circumstance into a good one was and is a key to Anne’s appeal, as she continues to provide emotional and moral support for those youths struggling to find their feet across the rough tides of the “real” world. Growing up amid these rapid social changes, I, too, felt the vicissitudes of young adulthood, when opportunities came in tandem with risks and the threat of failure. Anne’s steadfast devotion to her home, family, and community naturally became a source of comfort and reassurance. Her story assured me and my generation that normal life can be achieved, a life that, in all its seeming banality, can nonetheless be a good, meaningful, and happy one.

Alternatively, critics such as Yao, Cao, and Zhou have noted that adults can also learn from Anne. As a force for good and a beacon of courage, Anne became, for some Chinese readers, a figure of redemption within a particular social context whereby value became increasingly attached to personal success, defined by wealth, power, and luxury. One might say that Anne provided a channel for accessing the nostalgic past in the Chinese cultural memory, a time when personal and familial relationships seemed simpler, easier, and more lighthearted.

The summer of 2020 marks the fifteenth year since my first encounter with Anne. Fifteen years after I read Anne as a teenager, many of her readers, like me, have acquired a distance from their adolescence. Meanwhile, new readers of Anne continue to engage in the Green Gables world. The Chinese publishing market continues to invest in Anne.7 In 2019, Anne of Green Gables: The Graphic Novel, translated by Ren Zhan, was disseminated by Hunan Literature and Arts Publishing House.

Soon after, the full Anne series was republished by Beijing Yanshan Press as a newly designed boxed set with a beautifully made companion notebook included.

The translation work was initiated, again, by Ma Ainong, while the illustrations came from illustrator Lauren Mills’s 1989 version, with additional pictures provided by Chinese artist Wang Wencheng (who also illustrated the Emily trilogy). In 2020, Zhejiang Literature and Arts Publishing decided to publish the definitive text of Anne of Green Gables and package it together with two other works translated by Ma, Montgomery’s The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career and Liz Rosenberg’s House of Dreams: The Life of L.M. Montgomery. The publishers named the packaged set Green Gables Forever. (This is a literal translation from the Chinese.)

These newly compiled texts and translations allow readers who encountered Anne early in their lives but knew little about the biographical context of Montgomery’s life to revisit the books and appreciate them in a new light.

In China, a common publisher’s endorsement for the Anne books has been that they are “a lifelong present a mother gives to her daughter.”8 Although Anne’s readership reaches far more widely than what the publishers targeted, her legacy in China has indeed been a lifelong one, crossing time, space, and geographic boundaries. My story of growing up with Anne is therefore both unique and familiar. It testifies to Anne’s resilience and flexibility as a character and a figuration of adolescence that continues to speak to our shared humanity.

About the Author: Yan Du received her Ph.D. from the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge. Her doctoral research explores new approaches to girls’ authorship in Montgomery’s Emily trilogy and contemporary young adult fiction.

- 1 Ma, translator’s foreword to Anne of Green Gables, my trans., par. 3.

- 2 Cao, foreword to Further Chronicles of Avonlea, my trans.

- 3 Yao, translator’s foreword to Red-Haired Anne, my trans., par. 5.

- 4 Ma, translator’s foreword to Anne of Green Gables, my trans., par. 2.

- 5 Zhou, foreword to Anne of Green Gables, my trans.

- 6 Yao, translator’s foreword, par. 6.

- 7 Currently, more than fifty versions of Anne of Green Gables can be found on the Chinese publishing market.

- 8 A good example is the publisher endorsement for the packaged set Green Gables Forever mentioned earlier.

Works Cited

Cao, Wenxuan. Foreword. Further Chronicles of Avonlea, by L.M. Montgomery. Translated by Li Changchuan. Twenty-First Century Publishing, 2010.

Ma, Ainong. Translator’s foreword. Anne of Green Gables, by L.M. Montgomery. Translated by Ma Ainong. People’s Literature Publishing, 2015.

---, translator. Anne of Green Gables. By L.M. Montgomery, People’s Literature Publishing, 2004.

---, translator. Green Gables Forever boxed set. By L.M. Montgomery and Liz Rosenberg, Zhejiang Literature and Arts Publishing, 2020.

--- et al., translators. The Anne of Green Gables Complete Series. By L.M. Montgomery, Beijing Yanshan Press, 2021.

Ren, Zhan, translator. Anne of Green Gables: A Graphic Novel. By L.M. Montgomery, edited by Mariah Marsden, illustrated by Brenna Thummler, Hunan Literature and Arts Publishing, 2019.

Yao, Yao, translator. Red-Haired Anne. By L.M. Montgomery, Tsinghua UP, 2012.

Zeng, Xiaowen, translator. Fair Lady (Anne of Green Gables). By L.M. Montgomery, China Times Publishing, 2019.

Zhou, Guoping. “[Foreword: What We Can Never Miss Out in Life.]” Anne of Green Gables, by L.M. Montgomery. Translated by Guo Pingping. Yilin Publishing, 2019.