This article explores the reasons for Anne of Green Gables’s late arrival in Russia and examines three Russian translations of the novel, showing how different attitudes toward children’s literature and conceptions about girls’ books, particularly in the Russian society and literary system, shaped translation and marketing strategies.

Despite Anne of Green Gables’s belated entrance onto the Russian literary scene, the history of its translation and reception is both interesting and complex because several versions were published within a short period of time. Examining the three main Russian translations—Ania iz Zelenykh Mezoninov (Ania from Green Mezzanines) (1995), Istoriia Enn Shirli. Enn v Gringeible (The Story of Anne Shirley: Anne in Gringeibl) (2000), and Ania s fermy “Zelenye Kryshi” (Ania from “Green Roofs” Farm) (2008)1—within the contexts of their production and publication shows how translation is not limited by the language alone but shaped by ideology (both official state ideology and that of participants in the literary system such as translators, critics, and publishers) and by the poetics dominant in the receiving system at the time of translation.2 Naomi Seidman observes that applying “translation stories,” as a narrative approach that embeds translation in “the material, political, cultural or historical circumstances of its production,” allows us to view translation as a representation of “an unfolding of those conditions.”3 Translation stories of the Russian Annes reveal how different attitudes about the function of children’s literature and about girls’ books as a genre can shape translations and marketing of the same book in the same country in completely different ways and how these attitudes can influence and even hinder its reception.

There are several reasons for Anne’s late arrival in Russia. Initially, the few years between the novel’s publication in 1908 and the First World War was simply too short for any form of reception. Then the official censorship established shortly after the October Revolution of 1917 created a serious barrier: in a country where state interests were now put above everything personal and children’s literature was instrumental in creating new Soviet citizens, themes associated with pre-revolutionary life, such as family, home, and religion, were rejected as “bourgeois.”4 In this context, Anne, which focuses on the emotional development of a female protagonist and features religious elements, was ideologically unsuitable, even if the young heroine questioned rather than affirmed certain Protestant attitudes.

And yet, translations into Polish and Slovak show that a country’s belonging to the Eastern Bloc did not exclude the possibility of the novel’s publication and successful reception, although the translators into Polish and Slovak had to resort to adapting certain passages because of ideological constraints.5 Starting from the early 1960s, translators and publishers in Soviet Russia also practised the strategy of circumventing ideological restrictions through negotiations with editorial boards,6 but no one tried to champion Anne. There must have been more specific reasons that Anne remained so overlooked.

A closer look at the history of the Russian children’s literary system shows that the Russian reception of Anne was also hindered by a lack of interest in—and even a rejection of—female stories. A novel about a girl in a female-dominated community did not fit the stereotypical Russian image of Canada associated with a male hero out in the wild as presented by male nature writers, such as Grey Owl, Farley Mowat, and Ernest Thompson Seton, to name a few Canadian-associated writers whose work was translated.7 Yet a more serious obstacle was the long tradition of viewing girls’ books as a mediocre genre, a view that was established as early as 1912 when poet and translator Kornei Chukovskii attacked the phenomenally bestselling Russian author of girls’ books Lidiia Charskaya as “genii poshlosti” (“a genius of vulgarity”).8 Chukovskii’s opinion was so influential that this pattern of associating girls’ literature with inferior literary quality and false sentimentality remains even today. Systematic exclusion of both Russian and foreign girls’ literature from the official canon and the consequent disappearance of specifically female experiences as a theme in children’s literature continued—and continues—throughout the Soviet rule and beyond.9 The rare mentions of girls’ literature in post-Soviet handbooks reaffirm earlier attitudes by describing Charskaya’s books as mass literature10 and dismissing the works of Mary Mapes Dodge and Louisa May Alcott as reading material for girls only, because they are filled with “dukh melodramatizma” (“melodramatic spirit”).11

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when state censorship was abolished and translation became a means of creating new identities, overcoming the denigrating attitude toward girls’ books deeply ingrained in Russian culture required a dedicated advocate.12 This person was Marina Batishcheva, whose 1995 translation of Anne of Green Gables—Anja iz Zelenych Mezoninov (Ania from Green Mezzanines)—was the first to be published in Russia. Driven by her strong affinity for L.M. Montgomery as an author, Batishcheva initiated the translation project herself. When researching and looking for a publisher, she faced prejudice from snobbish librarians who refused to acknowledge Montgomery’s literary value as well as publishers who were reluctant to take risks with an unknown author. Yet publication became possible thanks to an editor friend from the St. Petersburg publisher Lenizdat. Anne of Green Gables was the first novel to be published in the new series Neznakomaia klassika. Kniga dlia dushi (Unknown Classics: Books for the Soul).13

The “Books for the Soul” title aptly names the cultural gap that the series seeks to fill—introducing literature focusing on the inner world that had been largely absent in Soviet times—and, in its reference to “Unknown Classics,” additionally attempts to suggest an alternative female canon of classic girls’ books by Anglo-American authors: Alcott, Susan Coolidge, Eleanor Porter, Jean Webster, and Kate Douglas Wiggin. For Batischeva, this project clearly was a strongly political, anti-Soviet statement. However, her rebellion consisted largely of substituting the ideology she rejected with another ideology she admired. In her published paratexts, she concludes that the philosophy of the Anne books is based on Protestant morality, which views harsh self-assessment and strict, even cruel, conscience, as virtues.14 While Batishcheva does acknowledge the importance of the questions Montgomery’s work raises about a woman’s position, she never addresses the compatibility of female liberation and fulfilment with the ideology of duty and self-denial she openly approves of. Batishcheva also fails to acknowledge that Montgomery uses some passages mentioning religion to challenge such restrictive beliefs. Batishcheva’s view of religion-based morality as an intrinsic value of Montgomery’s work is reflected in her documentary approach to translation, which results in non-idiomatic expressions and unnatural syntax that blunt the characters’ emotions and Montgomery’s lively tone.15

Batishcheva truly acted as Anne’s image-maker in post-Soviet Russia: she is responsible for establishing the reception pattern that links Montgomery’s work to other—sometimes overtly didactic—North American girls’ books, such as Coolidge’s Katy series, and situates Anne on the conservative end of the spectrum of girls’ literature. Such packaging, in combination with a word-to-word translation that hinders readability, is bound to cause misinterpretations. An extreme example of misreading Montgomery as a conservative author is the opinion expressed by critics Ksenia Moldavskaya and Maria Poriadina, who called Ania iz Zelenykh Mezoninov “koshmar” (“a nightmare”) when a lively child is moulded into a respectable member of “kvakerskogo obshestva” (“Quaker society”) by means of “uiutnoe nasilie” (“cozy violence”). The latter expression shows that they mistake Montgomery’s trademark descriptions of nature and beauty for a method to lure young female readers into accepting conservative roles.16

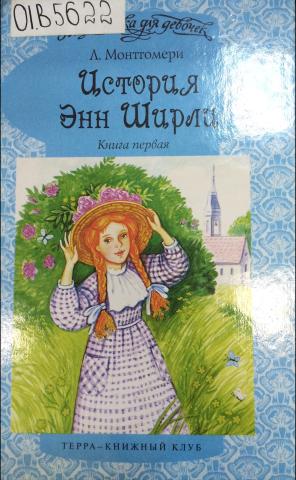

However, publishers’ importing of Protestant morality through North American books as an alternative to Soviet values was not the only way to build new identities. Russian children’s literature of the 1990s was marked by the spirit of anarchy, which was intended to challenge authority and shape critically thinking individuals instead of submissive citizens.17 While Raisa Bobrova, whose three-volume translation Istoriia Enn Shirli (The Story of Anne Shirley) was published in 2000 by Terra-Knizhnyi Klub in a series with the ideologically neutral title Biblioteka dlia devochek (Library for Girls), did not provide paratexts explaining her strategies, textual analysis reveals that she not only clearly recognized the anarchic impulses implied by Montgomery’s work but also emphasized them by intensifying descriptions of Anne’s behaviour and rewriting her speech in a colloquial style.

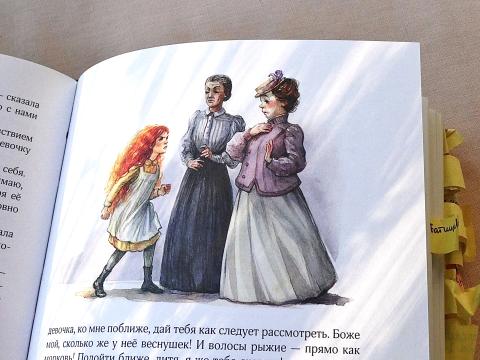

Thus, when Mrs. Rachel Lynde offends her, Anne jumps up “kak tigritsa” (“like a tigress”) and says she is “ubit’ gotova” (“ready to kill”)18 when people draw attention to her red hair. On the other hand, Bobrova systematically shortens and omits nature descriptions and passages concerning religion. While such adaptation was not enforced by censorship, Anne’s reflective and sensitive side did not fit the new poetics of overt irreverence that the translator chose to follow. Moreover, in the 1990s, entertainment for its own sake was often seen as the main function of children’s literature, and spiritual depth was neglected.19 Bobrova’s text is lively and fun to read, but the numerous alterations do not reflect the subtlety of Anne’s character. Additionally, the 1990s slang and occasional anachronisms, such as Marilla comparing Anne to a light bulb,20 add to the image of a contemporary audacious girl.

Ania s fermy “Zelenye Kryshi” (Ania from “Green Roofs” Farm), translated by Nataliia Chernyshova-Mel’nik and published by Enas-Kniga in 2008, reflects a return to conservative role models, which is clearly spelled out in the publisher’s policy. Enas-Kniga’s series “Malen’kie Zhenshchiny” (“Little Women”) is dedicated to “sentimental’nye devich’i povesti” (“sentimental girls’ novels”)21 and includes a vast number of translated titles from L.T. Meade through Alcott to Edith Nesbit. According to the chief editor Galina Khondkarian, all these books are carriers of eternal values, which by default means traditional expectations of women as kind, compassionate, and caring.22 Such packaging turns Montgomery into one of many interchangeable women writers who produced formula fiction and strongly reduces her achievements as an original and subversive author. This attitude disturbingly mirrors patriarchal ideology that idealizes woman in the abstract but diminishes a woman’s worth as an individual.23 While glorifying nostalgic girlhood in general, the publisher denigrates Montgomery when dealing with her specifically, through both paratexts and translations. On the blog run by Enas-Kniga, a post dedicated to Montgomery’s heroines describes them as non-feminists who are religious and care about domesticity (cozy home-making and love of good food) above all.24 Another post dismisses Anne as a copy of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm and goes as far as to suggest that literary experts have been reluctant to examine the similarities between the two books because they want to protect the Canadian tourist industry, which strongly depends on Montgomery’s iconic status.25

This latter accusation is especially scandalous because plagiarism is one of the strategies used by the Enas-Kniga translator Chernyshova-Mel’nik, who simply copied Batishcheva’s biographical note on Montgomery, changing the wording only slightly. Ascribing Anne to the sentimental genre, which in the Russian system automatically means low literary value, led to the translator and publisher applying insufficient quality control and trivializing the language. Chernyshova-Mel’nik not only had an insufficient command of English, which accounts for numerous mistakes, including Anne dying Diana’s eyebrows instead of tying her bows in chapter 19, but also used clichés such as “malyshka” (“little girl”) that rewrite the adventurous Anne as a stereotypical sentimental heroine, thus lending the story an insincere tone.

Still, the translations with ambivalent or conservative attitudes continue to be republished in different forms: the first three Anne books in Batishcheva’s translation were issued by Eksmo as Luchshaya klassika dlya devochek (Best Classics for Girls), with a conventional attitude toward romance emphasized by their pastel covers.

In 2018, Malysh, a well-known Russian publisher of children’s literature, commissioned Batishcheva to adapt Anne of Green Gables for younger readers. In the same year, publisher Kacheli chose Chernyshova-Mel’nik’s translation for their girls’ series due to its “readability.”26

Interestingly, visual packaging of the recent editions is ahead of the texts and publishers’ policies in depicting female freedom.

The Malysh cover depicts Anne as an “other,” a dreamer rather than a submissive daughter. The cover and many illustrations in the Kacheli edition reflect Montgomery’s feminism on several levels: by emphasizing Anne’s unconventional looks such as illustrating her freckled hands, using vibrant colours, and portraying her in nature, but also by depicting her as capable of rebellion and expressing anger.

These images signal an interest in female liberation as a literary theme and therefore suggest a need for a retranslation that would do justice to Montgomery’s unique feminist touch. It would require considerable effort to overcome prejudice against girls’ literature and include Anne in the Russian long-established tradition of well-translated literature, but doing so could become a political act that would be worth it in the end.

About the Author: Irina Levchenko is a Ph.D. candidate in transcultural communication at the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna, Austria, and a literary translator. In her Ph.D. thesis, she analyzes Russian translations and reception of the beloved Canadian classics Anne of Green Gables and other Montgomery novels, with a focus on the treatment of feminist elements as well as ideological and poetical reasons for various translation strategies and reception patterns. Her career as a translator on the Russian literary market includes work for Polyandria Publishing House and Azbooka-Atticus Publishing Group. She has translated picture books and children’s fiction from German as well as several other titles from German and English into Russian, including Shaun Bythell’s bestselling The Diary of a Bookseller and Confessions of a Bookseller.

- 1 In this article, I have used the Library of Congress transliteration system without diacritics for Russian book titles and words. Here and elsewhere I provide my own literal back translation.

- 2 These principles of translation are discussed in Lefevere, Translation 41.

- 3 Seidman, Faithful 9.

- 4 The context of the early period in Soviet children’s literature is discussed by Witt, “Translating” 114; Voskoboinikov, “Detskaya Literatura”; and Goodwin, Translating 30.

- 5 Dukátová, “Gender Roles” 5–9, and Wachowicz, “L.M. Montgomery” 7–35, give detailed accounts of Slovak and Polish reception of Anne, respectively. Dukátová, “Gender Roles” 5–6, has pointed out that certain passages concerning religion were rewritten or omitted in the Slovak translation because of ideological constraints. Batishcheva, in an email to me of 11 August 2016, has made similar observations about Polish translations.

- 6 Rudnytska, “Translation” 56.

- 7 See Cherniavskaya, “Priroda” 243-246; Meshcheriakova and Cherniavskaia, “Literatura” 193–201.

- 8 See Chukovskii, “Lidiia.”

- 9 See Luk’ianova, Kornei 227.

- 10 See Arzamastseva, “Massovaia” 187–89.

- 11 See Budur, “Soedinennye Shtaty” 151.

- 12 See Hellman, Fairy Tales 563–64.

- 13 The information about the publication process was provided in an email to me from Batishcheva, 11 August 2016.

- 14 Batishcheva, “Liusi Mod Montgomeri” and Batishcheva, Predislovie 5.

- 15 Examples of this can be found almost on every page and are difficult to render through back translation. Words as linguistic units are carefully preserved, but they do not function as a meaningful whole; the effect on the reader is reminiscent of a machine translation. On the whole, this rather paradoxical translation strategy unintentionally creates an impression that the novel is indeed a boring didactic narrative.

- 16 For this discussion see Rossiiskaia gosudarstvennaia detskaia biblioteka (Russian State Children’s Library). For more on Montgomery’s use of sensual descriptions for feminist purposes see Gammel, “My Secret Garden” 236–58, and Gammel, “Safe Pleasures” 114–30.

- 17 See Rudova, “Invitation” 334.

- 18 Montgomeri, Istoriia 63, 73.

- 19 See Voskoboinikov.

- 20 Montgomeri, Istoriia 62.

- 21 Labirint.

- 22 Labirint.

- 23 The problem of such a double standard in patriarchy is addressed by Gabriella Åhmansson in her analysis of Anne (Åhmansson, A Life 102–03).

- 24 Yandex Zen, “Desyat’ urokov.”

- 25 Yandex Zen, “Rebekka iz.”

- 26 Kacheli made this point in a Facebook message to me, 18 November 2019.

Works Cited

Åhmansson, Gabriella. A Life and Its Mirrors: A Feminist Reading of L.M. Montgomery’s Fiction, Volume 1: An Introduction to Lucy Maud Montgomery, Anne Shirley. University of Uppsala, 1991.

Arzamastseva, I.N. “Massovaia detskaia literatura” [“Mass Children’s Literature”]. Detskaia literatura: Uchebnoe posobie [Children’s Literature: A Handbook], edited by S.A. Nikolaeva and I.N. Arzamastseva, Akademiia, 1997, pp. 186–89.

Batishcheva, M. Iu. Email. 11 August 2016.

---. “Liusi Mod Montgomeri. Ot perevodchika” [“Lucy Maud Montgomery: Translator’s Note”]. Amerikanskaia i kanadskaia klassika dlia semeinogo chteniia [American and Canadian Classics for Family Reading]. http://web.archive.org/web/20071021004854/http:/familyclassics.narod.ru….

---. Predislovie [Foreword]. Anja iz Zelenych Mezoninov [Ania from Green Mezzanines], by Liusi Mod Montgomeri [Lucy Maud Montgomery], translated by Marina Batishcheva, Lenizdat, 1995, pp. 3–6.

Budur, N.V. “Soedinennye Shtaty Ameriki. Kanada” [“The United States of America. Kanada”]. Zarubezhnaia detskaia literatura [Foreign Children’s Literature], edited by N.V. Budur, et al., Akademiia, 2000, pp. 151–57.

Chernyavskaya, I.S. “Priroda u chelovek v proizvedeniiakh amerikanskikh i kanadskikh pisatelei” [“Nature and Man in the Works of American and Canadian Writers”]. Zarubezhnaia detskaia literatura [Foreign Children’s Literature], edited by I.S. Chernyavskaya, Prosveshchenie, 1974, pp. 243–46.

Chukovskii, K.I. “Lidiia Charskaya. Otryvki iz stat’i” [“Lidiia Charskaia. Excerpts from the Article”]. Bibliogid. https://bibliogid.ru/archive/pisateli/pisateli-o-chtenii/391-k-i-chukov….

Dukátová, Natália. “Gender Roles in Slovak Children’s Literature through the Lens of Anne of Green Gables.” The Shining Scroll, 2021, pp. 5–9.

Gammel, Irene. “‘My Secret Garden’: Dis/Pleasure in L.M. Montgomery and F.P. Grove.” The L.M. Montgomery Reader: Volume Two: A Critical Heritage, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 1999, pp. 236–58.

---. “Safe Pleasures for Girls: L.M. Montgomery’s Erotic Landscapes.” Making Avonlea: L.M. Montgomery and Popular Culture, edited by Irene Gammel, U of Toronto P, 2002, pp. 114–30.

Goodwin, Elena. Translating England into Russian: The Politics of Children’s Literature in the Soviet Union and Modern Russia. Bloomsbury, 2021.

Hellman, Ben. Fairy Tales and True Stories: The History of Russian Literature for Children and Young People (1574–2010), vol. 13, Brill, 2013.

Kacheli. Facebook message. 18 November 2019.

Labirint. “Geroini sentimental’noi detskoi prozy v serii ‘Malen’kie zhenshchiny’” [“Heroines of Sentimental Children’s Prose in the Series ‘Little Women’”]. https://www.labirint.ru/child-now/enas-malenkie-zhenschiny/.

Lefevere, André. Translation, Rewriting, and the Manipulation of Literary Fame. Routledge, 1992.

Luk’ianova, Irina. Kornei Chukovskii. Molodaia gvardiia, 2006.

Meshcheriakova, N.K., and I.S. Cherniavskaia, “Literatura Kanady” [“Canadian literature”]. Zarubezhnaia literatura dlia detei i iunoshestva [Foreign Literature for Children and Young People], edited by N.K. Meshcheriakova and I.S. Cherniavskaia, Prosveshchenie, 1989, pp. 193–201.

Montgomeri, Liusi Mod [Montgomery, Lucy Maud]. Ania iz Avonlei [Ania from Avonleia]. Translated by Marina Batishcheva, Eksmo, 2014.

---. Ania iz Zelenykh Mezoninov [Ania from Green Mezzanines]. Translated by Marina Batishcheva, Lenizdat, 1995.

---. Ania iz Zelenykh Mezoninov [Ania from Green Mezzanines]. Translated by Marina Batishcheva, Eksmo, 2015.

---. Ania iz Zelenykh Mezoninov [Ania from Green Mezzanines]. Translated, adapted, and abridged by Marina Batishcheva, Malysh, 2018.

---. Ania s fermy “Zelenye Kryshi” [Ania from “Green Roofs” Farm]. Translated by Nataliia Chernyshova-Mel’nik, Enas-kniga, 2008.

---. Ania s fermy “Zelenye Kryshi” [Ania from “Green Roofs” Farm]. Translated by Nataliia Chernyshova-Mel’nik, Kacheli, 2018.

---. Ania s ostrova Printsa Eduarda [Ania from Prince Edward Island]. Translated by Marina Batishcheva, Eksmo, 2014.

---. Istoriia Enn Shirli. V trech knigach. Kniga pervaia. Enn v Gringeible. Enn v Evonli. [The Story of Enn Shirli. In three volumes. Volume one. Enn in Gringeibl. Enn in Evonli]. Translated by Raisa Bobrova. Terra Knizhnyi Klub “Aleksandr Korzhenevskii,” 2000.

Rossiiskaia gosudarstvennaia detskaia biblioteka [Russian State Children’s Library]. “Bibliogid”: problema “gendera” v sovremennoi literature dlia podrostkov [“Bibliogid”: Problem of Gender in Modern Literature for Teenagers]. 4 May 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eKVZQJglmcY.

Rudnytska, Nataliia. “Translation and the Formation of the Soviet Canon of World Literature.” Rundle, Lange, and Monticelli, pp. 39–71.

Rudova, Larisa. “Invitation to a Subversion. The Playful Literature of Grigorii Oster.” Russian Children’s Literature and Culture, edited by Marina Balina and Larisa Rudova, Routledge, 2013, pp. 325–42.

Rundle, Christopher, Anne Lange, and Daniele Monticelli, editors. Translation Under Communism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

Seidman, Naomi. Faithful Renderings: Jewish-Christian Difference and the Politics of Translation. Chicago UP, 2006.

Voskoboinikov, V. “Detskaia literatura vchera i segodnia. A zavtra?” [“Children’s literature yesterday and today. And tomorrow?”]. Voprosy literatury [Questions of literature], no. 5, 2012. Zhulnal’nyi zal v RZh, “Russkii Zhurnal” [Magazine room in “Russian Magazine”], http://magazines.russ.ru/voplit/2012/5/v7-pr.html, currently not accessible.

Wachowicz, Barbara. “L.M. Montgomery: At Home in Poland.” Canadian Children’s Literature, no. 46, 1987, pp. 7–35.

Witt, Susanna. “Translating Inferno: Mikhail Lozinskii, Dante and the Soviet Myth of the Translator.” Rundle, Lange, and Monticelli, pp. 111–40.

Yandex Zen. Izdatel’stvo Enas-Kniga. “Desyat’ urokov schast’ia ot Liusi Mod Montgomeri” [“Ten Lessons of Happiness from Lucy Maud Montgomery”]. 20 May 2019. https://zen.yandex.ru/media/id/5a625266a936f4cefc14d880/desiat-urokov-s….

---. Izdatel’stvo Enas-Kniga. “‘Rebekka iz solnechnogo ruch’ia’. Istoriia odnogo plagiata” [“‘Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm’: A Story of One Plagiarism”]. 22 September 2019. https://zen.yandex.ru/media/id/5a625266a936f4cefc14d880/rebekka-iz-soln….