Sections

- Early Reception of Anne of Green Gables in Poland and Slovakia

- Effects of Communist Regime on Reception and Translations of Anne of Green Gables

- Challenges of Translating Names and Title

- Visual Design of Covers and Illustrations

- Anne of Green Gables in Contemporary Slovakia and Poland

- Academic Conversations about Anne of Green Gables in Slovakia and Poland

This conversation between Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz and Natália Dukátová focuses on the reception of Anne of Green Gables in Poland and Slovakia. It discusses, among other topics, the translations’ histories, the challenges posed to translators by L.M. Montgomery’s novel, and how Anne is positioned in Polish and Slovak culture today.

Early Reception of Anne of Green Gables in Poland and Slovakia

Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz (AW): Anne of Green Gables has a remarkably long history of reception in Poland; it has been present in the Polish publishing market for more than a century, so it has had time to become deeply rooted in our culture. In 2022, we celebrated the 110th anniversary of the novel’s first Polish translation, which was authored by R. Bernsteinowa and published by Michał Arct’s publishing house at the end of 1911.1 Interestingly, Anne’s first translator is a rather mysterious figure, as we are not even sure of her full name.2 She came from a Jewish family and translated mainly from Scandinavian languages. A few years ago, a research team from Jagiellonian University in Kraków discovered that her translation was based on Karin Jensen’s Swedish version, Anne på Grönkulla, the first-ever translation of Anne into a foreign language. (Polish was the third translation in the world, after the Swedish and Dutch ones.)3 Because Anne på Grönkulla means “Anne of Green Hill,” Bernsteinowa titled her version Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza, “Annie of Green Hill.”

There is also another curiosity about the first Polish Anne: its title page lists the author not as Lucy Maud Montgomery, but as … Anna Montgomerry! Yes, exactly, Montgomerry spelled with a double “r,” to misquote Anne. Why such a massive mistake in a book published by one of Poland’s leading booksellers of the time? Could it really have been a mere misprint? My guess is that the publisher may have deliberately mixed up the names to avoid paying for the copyright. These matters were still unregulated in Poland at the beginning of the twentieth century, and, in the Arct publishing house, such “mistakes” in names happened often enough to seem suspicious. The wrong name was repeated persistently in subsequent editions of Anne in 1919, 1921, and 1925. It was not until 1928 that Arct published Anne of Green Gables under Montgomery’s correct name—and almost immediately L.C. Page sued the Polish company for publishing and distributing the novel illegally. If we put two and two together, the conclusion is that the misspelled name of the author made it difficult for the copyright holders to identify the illegal editions. For the publishers who infringed copyright in order to minimize costs, it provided a certain “protective camouflage.”

But how about Slovakia? When was Anne translated for the first time, and is the translation veiled in any mystery?

Natália Dukátová (ND): Anne of Green Gables was first translated into Slovak in 1959—more than fifty years after the original book—by Jozef Šimo. He was already a respected translator from English to Slovak with an eye for detail and an eye for the complexity of both languages. The work came into the Slovak literary environment at a time when translations of literature for children and young people were dominated by translations from Russian. Anne was lucky that it was already a relatively “old” book, describing the past. If it was set in the contemporary world with the same plot and the same characters, Anne would almost certainly have been banned. The only books about the contemporary world that were allowed to be published in the 1950s were from the Soviet Union, and these automatically included communist propaganda.4 Scholarly discussion of the book hardly took place at all. The book won hearts only by the positive recommendation of enthusiastic readers. I find it interesting, for example, that in the Czech Republic (Slovakia was part of Czechoslovakia from 1918 to 1992) Anne was translated for the first time in 1982, and so far the book is nowhere near as popular there as it is in Slovakia.

Effects of Communist Regime on Reception and Translations of Anne of Green Gables

AW: I remember you saying at the L.M. Montgomery Institute conference in 2022 that Anne was never fully translated into Slovak during the communist era. Can you tell something more about the reasons why?

ND: Anne of Green Gables was not translated into Slovak fully until 2015, simply because it couldn’t be. Translation during the communist regime was controlled by censorship. Especially in the 1950s, when Anne was translated for the first time, generations of young boys and girls had to be heroes, helping others, fighting for the future, and defending the motherland. The authorities considered problematic any works that included sentimentality and infantilism, which were in conflict with communist ideology.

AW: Sentimentality, infantilism, and perhaps religion?

ND: Yes, the biggest problem was the references to God, prayers, Christianity, and religion itself. The communist regime enforced atheism, and, especially in the 1950s, any displays of faith were punished. In Anne, as we know, there are many references to religion. Some were untouched in translation, but others were either entirely erased or radically edited. For example, translator Jozef Šimo had a difficult task in passages that mention God or Providence or that show people praying, attending church, or publicly professing their faith and commitment to religious institutions and practices. Šimo opted to change God to “happiness” (šťastie) and “the Almighty” to “relying on myself” (spoľahnutie sa na seba). Nevertheless, a praying Anne surprisingly remains in the seventh chapter, as does a sentence in which Anne explains to Marilla who God is. The passages were saved probably because without them the entire chapter would make no sense. In other parts of the book, praying was replaced by words such as “obey” (byť poslušný) or “be good” (byť dobrý).5 Although Anne of Green Gables had to wait more than one hundred years to be fully translated into Slovak, the quality of the new translation by Beata Mihalkovičová is so bad that I would rather read the old edition for another one hundred years.

How about Poland? Was the situation with translation to Polish similar to Slovak?

AW: Well, in Poland it was different with Anne, even though our countries were under the same Soviet rule. Unlike Montgomery’s other novels, Anne of Green Gables was not subjected to much suppression during the communist regime. Perhaps its already being well established in Polish culture contributed to this. In any case, it did not attract the attention of censors. Maybe they “forgot” that the book was not Polish because Bernsteinowa’s translation employed a far-reaching strategy of domestication.6

ND: Domestication sounds very similar to the principles of translation here in Slovakia. Did domestication in translation refer only to personal names or also to places and things?

AW: Bernsteinowa Polonized the names and some significant nouns, rooting Anne’s world in Polish culture and realities. A good example of this is her rendering of Canadian “farms” as “dworki” [manors], a word that is strongly rooted in Polish landowning tradition. However, this was not ideologically based, as it was in the Slovak translations you mentioned, but rather culturally based—the translator wanted to neutralize the traces of foreignness for the benefit of young Polish readers.

ND: So was Anne in any way censored in Poland during the communist era?

AW: As far as I know, it was not subject to any censorship—not even the passages on religion such as you describe falling victim to censors in Slovakia. On the other hand, between 1947, when the first postwar edition was published in Wrocław by M. Arct and Dom Książki Polskiej [The House of Polish Book], and 1956, when the so-called “thaw” (the relaxation of the communist regime resulting in liberalization of culture) took place,7 Anne was not reissued. It is notable, however, that in 1951, at the time of the introduction of socialist realism as an official ideology, Anne was not included on the so-called “purgatory list,” a secret register of books subject to immediate withdrawal from libraries.8 Yet this list included, for example, Kilmeny of the Orchard and The Blue Castle.

Challenges of Translating Names and Title

AW: We talked a little about domestication in the first Polish Anne. What was the principal strategy of translating the novel into Slovak?

ND: Well, it’s worth mentioning that the development of literature, especially children´s literature, in Slovakia depended on translations. We translated a lot, mainly from Russian, but also from other languages, such as English and French. One of the most popular strategies of translation was domestication. This practice assumed that the translated text should flow as if it were written in the target language. There was also the issue of modernization: “old” language was usually replaced by modern expressions. And, especially in children’s books, if there were names that could cause comprehension problems or problems that might alienate readers, they needed to be translated. For example, the names “Anne” and “Matthew” exist in Slovakian, in a slightly different form, as “Anna” and “Matej,” so the familiar Slovakian forms were used. However, the name “Diana” remains the same in translation, as it exists as “Diana” in our language. On the other hand, equivalents for “Marilla” and “Gilbert” do not exist in our language, so in translation they remained as written in the original.

AW: This is very interesting! In Poland it was quite similar. At the beginning of the twentieth century, when Anne of Green Gables was first translated into Polish, our children’s literature was still in its initial phase of development, and translations—especially from Western languages—contributed significantly to its evolution. For this reason, translated literature greatly influenced Polish juvenile literature; for example, Anne of Green Gables (together with Little Women by Louisa May Alcott) provided a new model of the girl heroine, which was explored by Polish writers in the interwar period.9 But when it comes to translation strategies, the basic principle—at least in children’s literature at that time—was also domestication, as Friedrich Schleiermacher would have it, “bringing the original closer to the reader.”10 In the first Polish Anne, then, names that have Polish equivalents were translated (“Marilla” as “Maryla,” “Matthew” as “Mateusz,” “Jane” as “Janka,” and so on), and those that do not have Polish equivalents were retained in English (for example, “Gilbert” and “Ruby”). Such a pattern was established by Bernsteinowa, and all subsequent translations followed it closely, until the first polemical translation by Agnieszka Kuc (2003), which kept all names in the original—all except Anne’s.11 Unfortunately, in the reissue of this translation, the publisher decided to restore the Polonized names. The next polemic translation, by Pawel Beręsewicz (2012), retained all the original names except “Anne,” “Matthew,” and “Marilla.” Only the latest translation by Anna Bańkowska, published in 2022, boasts all the original names without exception. As you can see, we have come a long way from domestication to foreignization!

But I guess that for the Slovak translators, just as for the Polish ones, it was not the names that posed the biggest challenge, but the title. Am I right?

ND: Definitely. The biggest challenge and question of translating Anne of Green Gables was how to translate the title. The word “gable” has a different meaning in Slovakian than in English. It means “mountain peak” (štít), which could not be translated as Anne of Green Peak because that would completely change the meaning of the title. Also, peaked (gable-end) roofs are not common in Slovakia, so our language does not even have a word for them. Therefore, the literal translation of Anne of Green Gables would make no sense at all, and the translator had to look for an alternative that would not deviate much from the original but still capture the essence. The Slovak name Anna of Green House (Anna zo Zeleného domu) thus became a kind of “terminus technicus” over the years, a name that did not change, something like a brand.

AW: Well, again we share this translational predicament: in Poland the greatest challenge was the title too, even though the first translator had little problem with it—she was, after all, translating from Swedish. She did not have to worry that in Polish “gable” translates as “szczyt” (“peak”), and peak also has a second, more widespread meaning (“mountain peak”), exactly as in Slovak. Bernsteinowa established the title Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza as canonical and for the entire 110 years no translator ventured to challenge it until Bańkowska broke with the traditional title. Her translation is entitled Anne z Zielonych Szczytów [Anne of Green Gables/Peaks], so there is no “Green Hill.” Most interestingly, for the translators of Anne in Poland after Bernsteinowa, the greatest challenge turned out not to be the real translation problems, such as intertextual references to Scottish, English, and American literature or to the flora of Prince Edward Island, but precisely the translation tradition and the readers’ attachment to the old version.

ND: This is very different than in Slovakia, where there was no tradition and therefore there were no attachments!

AW: And, yes, Bańkowska was quite aware that she was embarking on a new, “rebellious” translation of Anne. She wrote in her preface:

In giving my readers a new translation of one of the most iconic novels, I am aware of the “betrayal” I am committing against the generation of their mothers and grandmothers, among whom I include myself. … I admit my guilt: I killed Annie and demolished Green Hill. … However, I ask for a lenient punishment, considering that someone at some point had to undertake this ungrateful task.12

Visual Design of Covers and Illustrations

ND: Let’s talk now a bit about the “looks” of Polish and Slovak Anne. Since you have such a long history of reception of Anne in Poland, I bet the history of editions and covers is also interesting.

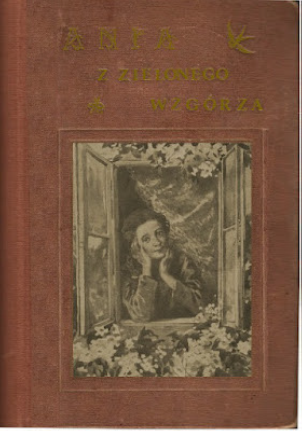

AW: Yes, indeed! Curiously enough, the cover of the first Polish translation referred in some ways (perhaps coincidentally) to L.C. Page’s first edition: we had different-colour versions, chestnut and celadon (hardcover in cloth binding), as well as white (paperback). However, the cover image did not depict the young woman from the Delineator13 but a smiling, slightly pensive girl in a window framed by greenery and flowers, as if the illustrator had in mind the scene when Anne looks out of the window for the first time and sees the Snow Queen in bloom. A completely different cover, far less idyllic, was designed by Bogdan Zieleniec for the 1956 edition; as Andrea McKenzie points out, it shows postwar emptiness and sadness but also a certain yearning for home, a safe haven.14

The 1990s and 2000s, on the other hand, were a festival of flamboyant covers, mostly cheap editions that were clumsy but attractive with their rich colours.

Later covers also made many references to Sullivan’s iconic film.15

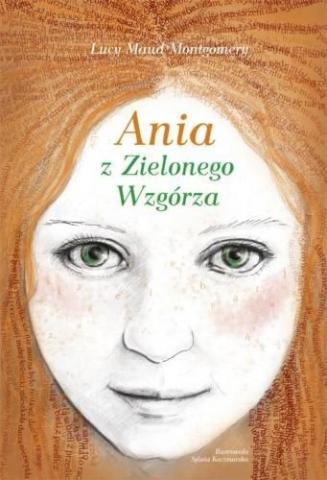

In my opinion, the most interesting visualization of Anne was designed by Sylwia Kaczmarska for Beręsewicz’s 2012 translation: the cover features Anne’s face with big, grey eyes, the freckles on her cheeks made of scattered letters, and her red hair made up of sentences taken from the book.

I spotted this edition in PEI, at the L.M. Montgomery homestead in Cavendish. But I don’t remember seeing any Slovak cover there.

What is the story of Anne editions in your country, Natália?

ND: Unfortunately, there is not much interesting history in the Slovak version. From 1959 until 1994, the cover and illustrations remained the same. The cover is quite unattractive, especially for children—a white-and-green base and a pen-drawing of a girl (Anne) holding a flower.

Inside the book are similar black-and-white illustrations of Anne and other characters.

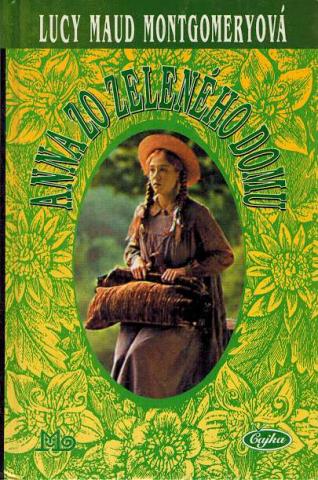

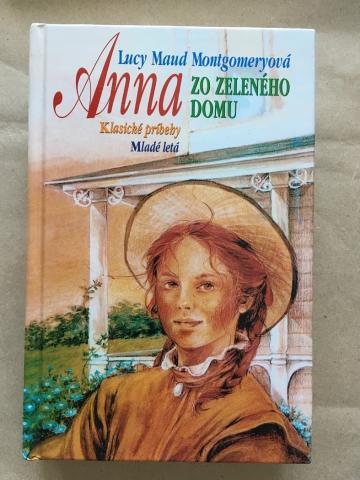

In the 1990s, when the Sullivan films were hugely popular, Megan Follows appeared on the cover, but the design of the cover is, again, quite unaesthetic.

In 2002, there is a “new” Anne, which also isn’t very innovative, as the cover was taken from an older German edition.

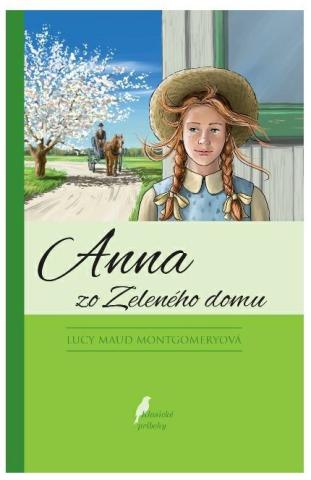

In 2015 (and I can say “finally!”), we had a cover that met the criteria of an appealing, eye-catching, original cover. Anne is colourful, with a smile on her face, while Matthew is approaching the train station in his buggy.

The “collection” ends with one more version of the book, from 2019, but nothing original again as it was taken from the 2014 Aladdin (Simon and Schuster) Canadian edition.16

Anne of Green Gables in Contemporary Slovakia and Poland

ND: During the 2022 L.M. Montgomery Institute conference, we talked about the very different contemporary reception of Anne of Green Gables in Poland and Slovakia—you have such a big community of fans! Is Anne generational reading in Poland? That is, is the novel something that grandparents and parents share with their children?

AW: It definitely is generational reading—for more than a century, Polish readers have grown up with the book. Social-media discussion around the new translation by Bańkowska often brought up—and continues to bring up—that Anne of Green Gables is a link between generations in Poland. Some older readers, who hold “Green Hill” in great affection, even accused the translator of “destroying their childhood.” And I can assure you, the discussion about the newest version was really quite heated!17

But tell me more about your situation. Does Anne provoke any stir in the general public?

ND: Anne of Green Gables in Slovakia unfortunately doesn’t provoke any public discussion—good or bad—at all. The only discussions are on some bookstore pages on Facebook, as readers like to know which Slovak translation is better and which one to buy. But on the other hand, the book was always hugely popular and is definitely a generational book. When Anne is mentioned anywhere, there are people of all ages who have read it and very much enjoyed it. It’s a book that grandma would give to her granddaughter. I have read many Internet discussions about Anne, and no one ever says that they didn’t enjoy the book. Everyone seems not just to like it but to love it. The book brings people together for generations. But we actually don’t have any fan community in Slovakia.

AW: In Poland, it is very different. Montgomery’s fan community is very strong, I am happy to say. There are several fan groups on social media and three bloggers who create sites dedicated solely to Montgomery. Bernadeta Milewski, who has a house in Park Corner, PEI, runs Kierunek Avonlea (“Direction Avonlea”) and is the soul of Montgomery’s Polish fan community. Agnieszka Maruszewska runs Pokrewne dusze. Świat Lucy Maud Montgomery w Polsce (“Kindred Spirits. The World of L.M. Montgomery in Poland”), where she presents the results of her extremely interesting research into the early Polish reception of Montgomery’s books. Another blog, run by Stanisław Kucharzyk, is Zielnik L.M. Montgomery (“L.M. Montgomery’s Herbarium”); it is devoted to the flora of Prince Edward Island.18 There is also the Dom Echa/Echo Lodge blog by Michał Fijałkowski, who discusses girls’ novels in Polish translation, especially those by Alcott, but also including Montgomery.

Let me give you an example of how important the Montgomery fan community is in Poland: we (I can say “we,” as I proudly count myself among them) had an influence on the choice of titles for the next parts of the Anne series in Bańkowska’s translation. At a meeting with the translator prior to the release of Anne z Zielonych Szczytów, she revealed what the titles of the next parts were to be. The fan community was not keen on these, so a survey was carried out on one of the Facebook groups, from which it emerged that readers would prefer more traditional titles, more faithful to the original ones. And the publishing house listened to the voice of the Polish Montgomery fan community, which really shows how engaged, important, and powerful it is!

ND: I would say! Lucky you!

Academic Conversations about Anne of Green Gables in Slovakia and Poland

AW: Is the academic reception of Montgomery also so different in Poland and Slovakia? Are her life and oeuvre subject to any scholarly discussions in academia?

ND: As far as I know, academic conversations about Anne of Green Gables almost do not exist in Slovakia. There is only one academic discussion about the book from 2014, when a scholarly article raised the demand, or need, for a complete and definitive translation. Thanks to this discussion, in 2015 the missing passages were added to the text, and it was the first complete edition of Anne of Green Gables.

I suspect it is different in Poland?

AW: Yes, as Montgomery definitely is discussed in academia, although more intensively only in recent years. In September 2022, the first Polish conference devoted exclusively to Montgomery’s work took place at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, organized by my colleagues and myself. Our focus was primarily Anne of Green Gables, as the conference was planned to mark the aforementioned 110th anniversary of its first Polish translation. For three days we celebrated Anne’s “long life” in Poland, discussing translations into other languages (French, Italian, Czech, Slovak, Swedish, and Chinese) and the role of fashion and religion, the empowerment of female characters, intertextuality, covers and illustrations, and many other fascinating topics. There was a meeting with translators (Bańkowska, Kuc, and Beręsewicz) for the general public and with Polish bloggers on Montgomery. These discussions are, in a sense, still ongoing, as we are currently working on a post-conference co-edited volume, which will be the first academic publication in Poland entirely and exclusively devoted to the author of Anne of Green Gables. We can’t wait to announce its publication to the Polish (and international!) community of Maud’s scholars, fans, and admirers!

About the authors:

Natalia Dukátová received her doctorate from the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava in world literature studies. Her academic interests are Slovak children’s literature, Russian and Soviet children’s literature in translations, and world children’s literature (mainly Anne of Green Gables). She has authored many reviews and academic articles about children’s literature and cooperated on a chapter in an academic book, Slovník slovenských prekladateľov umeleckej literatúry L–Ž [Dictionary of Slovak Translators of Fiction Literature Twentieth Century L–Ž].

Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Polish and Classical Philology and researcher in the Children’s Literature and Culture Research Team at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, Poland. She received her doctorate in 2022 from Adam Mickiewicz University on the Polish translation reception of works by George MacDonald, J.M. Barrie, and Cicely Mary Barker. Her academic interests include English children’s literature of the Golden Age, Polish juvenile writings, and children’s literature translation studies. She has authored two monographs and numerous academic articles and book chapters; she is also a literary and academic translator.

Acknowledgement: Part of the article by Aleksandra Wieczorkiewicz was funded in whole or in part by the National Science Centre, Poland, grant number 2021/41/B/HS2/00876. For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC-BY public copyright licence to any author accepted manuscript (AAM) version arising from this submission.

- 1 The question of when the first Polish translation of Anne was released is somewhat complicated. The book was published in two volumes, the first volume being dated 1912 and the second volume 1911. This was most likely because it was published as a Christmas gift book, and it was not unusual for Polish publishers to give the following year’s date for such publications. Based on archival research, Agnieszka Maruszewska proved that Anne was already available in Poland by mid-December 1911, as the first reviews and mentions in the press appeared then. However, why exactly the second volume was given an earlier date and the first a later one remains a mystery. See Agnieszka Maruszewska’s blog, Pokrewne dusze: Świat L.M. Montgomery w Polsce [Kindred Spirits: The World of L.M. Montgomery in Poland], http://pokrewne-dusze-maud.blogspot.com/2017/03/pierwsze-recenzje-ani-z….

- 2 This is also discussed by Lipinski, “Pat, Anne, and Other.”

- 3 The results of this research are presented in the article by Oczko, Nastulczyk, and Powieśnik, “Na szwedzkim tropie.”

- 4 For more on this subject, see Dukátová, “Gender Roles” 5–9.

- 5 For more on this subject, see Dukátová 5–9.

- 6 In her analysis of the strategy of domestication evident in the names of food and traditions in the Polish translations of Anne of Green Gables, Pat of Silver Bush, and Jane of Lantern Hill, Lipinski discusses some examples by Bernsteinowa; see also Zborowska-Motylińska, “Translating Canadian Culture” 153–61.

- 7 For more on historical and ideological transitions in Polish literature for young audiences, see Czernow and Michułka, “Historical Twists.”

- 8 See Cenzura PRL.

- 9 For more on this subject, see Wieczorkiewicz, “Inspiration from Translation” 184–86.

- 10 Schleiermacher, “On the Different Methods” 51–71.

- 11 On Polish polemical translations, see Pielorz, “Does Each Generation” 107–21.

- 12 Bańkowska, preface to Anne z Zielonych (my trans.).

- 13 See Gammel, Looking for Anne 231–32; Woster, “The Artists” 1–5.

- 14 McKenzie, “Patterns” 143–44.

- 15 For a compilation of all Polish covers of Anne of Green Gables and other Montgomery novels, see Maruszewska, Pokrewne Dusze.

- 16 Cover by Julene Harrison, 2014.

- 17 See, for example, the comments under the posts on the Facebook profile of the Marginesy Publishing House from January and February 2022.

- 18 For example, Kucharzyk coined a Polish name for mayflowers in Bańkowska’s translation; see Lipinski.

Works Cited

Bańkowska, Anna, translator. Anne z Zielonych Szczytów [Anne of Green Gables]. By Lucy Maud Montgomery, Marginesy, 2022.

Beręsewicz, Paweł, translator. Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza [Annie of Green Hill]. By Lucy Maud Montgomery, Skrzat, 2012.

Bernsteinowa, R., translator. Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza [Annie of Green Hill]. By Anna Montgomerry [Lucy Maud Montgomery], Księgarnia M. Arcta, vol. 1, 1912; vol. 2, 1911, https://polona2.pl/item/ania-z-zielonego-wzgorza-powiesc-cz-2,MTQyODkwMjE0/2/#info:metadata.

Cenzura PRL. Wykaz książek podlegających niezwłocznemu wycofaniu 1 X 1951 r. [People's Republic of Poland Censorship. List of books subject to immediate withdrawal on October 1, 1951], foreword by Norbert Tomczyk and Iwona Bednarska, introduction by Zbigniew Żmigrodzki, Wydawnictwo i Księgarnia Nortom, 2021.

Czernow, Anna, and Dorota Michułka. “Historical Twists and Turns in the Polish Canon of Children’s Literature.” Canon Constitution and Canon Change in Children’s Literature, edited by Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer and Anja Muller, Routledge, 2017, pp. 84–104.

Dukátová, Natália. “Gender Roles in Slovak Children’s Literature through the Lens of Anne of Green Gables.” The Shining Scroll, 2021, pp. 5–9. https://lmmontgomeryliterarysociety.weebly.com/uploads/2/2/6/5/226525/t….

Fijałkowski, Michał. Dom Echa/Echo Lodge, http://dom-echa.blogspot.com/.

Gammel, Irene. Looking for Anne: How Lucy Maud Montgomery Dreamed Up a Literary Classic. Key Porter Books, 2008.

Kuc, Agnieszka, translator. Ania z Zielonego Wzgórza [Annie of Green Hill]. By Lucy Maud Montgomery, Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2003.

Kucharzyk, Stanisław. Zielnik L.M. Montgomery [L.M. Montgomery’s Herbarium], https://zielnikmontgomery.blogspot.com/.

Lipinski, Joanna. “Pat, Anne, and Other Montgomery Characters in the Polish Kitchen.” Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, https://journaloflmmontgomerystudies.ca/international-notes/Lipinski/Pa….

Maruszewska, Agnieszka. Pokrewne Dusze. Świat L.M. Montgomery w Polsce [Kindred Spirits. The World of L.M. Montgomery in Poland], http://pokrewne-dusze-maud.blogspot.com/.

McKenzie, Andrea. “Patterns, Power and Paradox. International Book Covers of Anne of Green Gables across a Century.” Textual Transformations in Children’s Literature. Adaptations, Translations, Reconsiderations, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, Routledge, 2014, pp. 127–54.

Mihalkovičová, Beata, translator. Anna zo Zeleného domu [Anne of Green Gables]. By Lucy Maud Montgomery, Slovart, 2019.

Milewski, Bernadeta. Kierunek Avonlea [Direction Avonlea], http://kierunekavonlea.blogspot.com/.

Montgomery, Lucy Maud. Anne of Green Gables. Vintage, 2013.

---. Anne of Green Gables. Translated by Rozalia Bernsteinowa, Nasza Księgarnia, 1956.

Oczko, Piotr, Tomasz Nastulczyk, and Dorota Powieśnik. “Na szwedzkim tropie Ani z Zielonego Wzgórza. O przekładzie Rozalii Bernsteinowej” [“On the Swedish Traces of Anne of Green Gables. On the Translation by Rozalia Bernsteinowa”]. Ruch Literacki [The Literary Movement], no 3, 2018, pp. 261–80.

Pielorz, Dorota. “Does Each Generation Have Its Own Ania? Canonical and Polemical Polish Translations of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.” Negotiating Translation and Transcreation of Children’s Literature, edited by Joanna Dybiec-Gajer, Riitta Oittinen, and Małgorzata Kodura, Springer, 2020, pp. 107–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2433-2_7.

Schleiermacher, Friedrich. “On the Different Methods of Translating.” Translated by Susan Bernofsky. The Translation Studies Reader, edited by Lawrence Venuti, Routledge, 2021, pp. 51–71.

Šimo, Jozef, translator. Anna zo Zeleného domu [Anne of Green Gables]. By Lucy Maud Montgomery, Mladé letá, 1975, 1991, 2015.

Wieczorkiewicz, Aleksandra. “Inspiration from Translation. The Golden Age of English- Language Literature for Children and Its Impact on Polish Juvenile Fiction.” Retracing the History of Literary Translation in Poland. People, Politics, Poetics, edited by Magda Heydel and Zofia Ziemann, Routledge 2021, pp. 181–96.

Woster, Christy. “The Artists of Anne of Green Gables: A Hundred Year Mystery.” The Shining Scroll, 2007, pp. 1–5.

Zborowska-Motylińska Marta. “Translating Canadian Culture into Polish: Names of People and Places in Polish Translations of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.” Acta Universitatis Lodziensis, Folia Litteraria Anglica, no 7, 2007, pp. 153–61.

Banner image: Close up of wallpaper at Green Gables Heritage Place. Photo by Natália Dukátová.