Sections

- Abstract

- Carrying Anne to the Threshold

- A Year of Loss, Grief, and Mourning

- The Tasks of Mourning

- Task 1: Accepting the Reality of the Loss

- Task 2: Working Through the Pain of Grief (and Tragedy)

- Task 3: Adjusting to an Environment in Which the Deceased Is Missing

- Task 4: Find a Connection with the Deceased While Beginning a New Life

- How Montgomery Has Shaped Me as a Rabbi Chaplain

- Reading Anne and Grappling with Montgomery as a Person

- Conclusion

Abstract

How did Anne’s wisdom assist my coping with my mother’s mental illness and traumatic death? This essay draws on William Worden’s four tasks of mourning and explores Anne’s willingness to outwardly express strong emotion in response to death and other losses. Today, Anne’s wisdom guides me in my work as a chaplain.

To my door came grief one day

In the dawnlight ashen grey

All unwelcome entered in,

Took the seat where Joy had been ...

- L.M. Montgomery, The Blythes Are Quoted1

Carrying Anne to the Threshold

After three decades of struggling to survive with bipolar disorder, my mother ended her life on Labor Day weekend in early September 1982. I was home that weekend, poised between orientation and my first semester of law school. In keeping with Jewish tradition, we held her funeral right away, then sat Shiva, several days during which we stayed at home, received family, friends, and neighbours, prayed at nightly home-based religious services, and tried to take in the reality of our upended lives. I considered not returning to law school right away. The thought of days and nights filled with intellectually rigorous study amid strangers seemed overwhelming. However, I thought spending an entire year out of school at home meant boredom that by January would unnecessarily add suffering to my grief.

I walked through that fall and winter in a fog of tears and exhaustion, occasionally relieved by connection with beauty, moments of my essentially buoyant spirit rising, the comfort of close friends and family. Yet sadness and traumatic memories predominated. I felt fragile. The assistant dean told my professors why no one should subject me to the harsh Socratic questioning that characterizes law school’s first year.2 As part of my inner bargain for attending school at all, I permitted myself to walk out of a lecture hall if I felt like crying and not to study when my grief surfaced.

When I returned home for winter break, the Anne of Green Gables series beckoned like a wise, patient friend. I brought the books to law school to begin my second semester in mid-winter 1983. Twenty-two years old, I stood at the threshold of a long road of healing, a journey that continues today. This article traces how the Anne series helped me cope as I grew into a young adult and explores how specific scenes and passages may have spoken to me while I approached William Worden’s tasks of mourning3 in the first months after my mother’s death.

I can barely remember my life without Anne. By the time we moved from Queens, New York, to central New Jersey before I turned six, an illustrated, abridged edition of Anne of Green Gables accompanied us in the moving truck. Five years later, my parents bought me what I thought, for many years, was the entire series. I began my approximately biennial cycle of reading all the books, except for Chronicles and Further Chronicles of Avonlea, which did not have enough Anne in them to hold my interest.

The Anne series has served as a therapeutic and inspiring companion throughout my life, although like other reiterative readers, what I drew from each reading changed with my stage of maturation, life circumstances, and knowledge of the wider world. I experienced the Anne books as both a safe retreat from my world made increasingly unpredictable by my mother’s worsening mania-fuelled emotional abuse, and an opportunity to experiment with feeling orphaned during times my mother disappeared into depression, spending her time outside of work in naps that lasted until dinnertime. I experienced “mother loss” both before and after my mother’s death, and so likely was drawn to Montgomery’s novels because, as Rita Bode writes, “[t]he search for the lost mother, the attempt to locate her emotionally, psychologically, and physically, haunts Montgomery’s fiction.”4 In similar fashion to the readers described by Catherine Sheldrick Ross and Åsa Warnqvist, “Anne as a character [invited me] to make intensely felt connections between the fictional world of Anne and [my] own everyday [life].”5

At eleven, when reading the series for the first time, I was the same age as Anne when readers first meet her. As a tomboy more interested in perfecting my driveway basketball skills than my wardrobe, I quickly read past Anne’s interest in puffed sleeves to linger on her escapades walking a ridgepole or floating on a raft on Barry’s Pond. I was a brainy girl and nascent lesbian beginning to experience romantic crushes. Anne’s devotion to academic excellence and romantic friendships with Diana Barry and Leslie Moore6 validated my life choices, even as those same choices alienated me from many female peers, who by middle school curbed their intellectual expression and focused on attracting male attention. Fiction about orphans attracted me because orphans had to be more resilient and resourceful; they lacked parents and often did not fit in. Like other serial readers of the Anne series, “I wanted to be Anne,”7 in her insistence on being herself, in her devotion to lifelong female friendship, and in her straining against the gender norms of her day.

As I entered my mid-teens, reading Anne helped me cope with my mother’s accelerating fluctuation between mania and depression and shrinking periods of psychological balance. “Coping” can be defined as “conscious, volitional attempts to regulate the environment or one’s reaction to the environment under stressful conditions.”8 I could not control or even reliably predict my mother’s abrupt mood changes. However, I attempted to regulate my response, mostly by learning to suppress my appropriate expression of emotion, hoping that remaining calm and emotionally neutral would keep me safer from her outbursts. Reading the Anne series gave me a gentler world to withdraw into, with Anne fulfilling my fantasy of free emotional expression. This disengagement coping strategy, while effective in the moments of reading, likely also contributed to my increasing bouts of despondency and perseverative thoughts about actual or potential conflicts with my mother. Researchers have linked higher levels of “intrusive thoughts and psychological distress” to coping through disengagement.9 Nevertheless, as an adolescent living at home with limited autonomy, disengagement likely seemed the best coping strategy I could access.

Reading Anne in the years before my mother’s death also enabled coping strategies with more constructive long-term effects. Anne’s ability to adapt to circumstances beyond her control inspired me to engage in secondary control coping techniques such as distraction, acceptance, and positive thinking.10 Young Anne’s stories of her months at the orphan asylum and in various foster homes and her critical musings about her appearance are replete with flights of imagination that distract her from disagreeable realities. She retains a protected interior self despite harshly negative voices from those who exploit her as a servant. Anne models positive thinking for herself and others. In Green Gables, she tells Marilla she is determined to enjoy their buggy ride even though she assumes it will end with her being returned to the orphan asylum.11 In Windy Poplars, Anne relies on “an unaccountable feeling” to keep hoping to establish a friendship with the prickly Katherine Brooke and focuses on new friends, humour, and Gilbert’s letters to assuage her misery over the Pringle clan’s antagonism. When trying to persuade Katherine to come to Green Gables with her for Christmas, Anne admonishes her to “[o]pen your doors to life … and life will come in.” When the still reluctant Katherine ultimately agrees to come and enjoys herself, the two women learn about each other’s love-starved past. Hearing Katherine speak despairingly that she will never become happy or likeable, Anne advises her to focus on healing and look to the future with optimism.12

Anne also seeks social support throughout her life, first through imaginary friends Katie Maurice and Violetta in her two foster homes, then through deep friendships with the wide variety of kindred spirits she encounters through the years, beginning with Matthew and Diana and continuing at least until her first years of marriage. I emulated Anne by cultivating intimate friendships with a select few girls from my neighbourhood and school and by imagining Anne appearing at my door, eager to learn how the world had changed since the early twentieth century.

My personality provided fertile ground to receive Anne’s wisdom about surviving hard times. My parents described me as a cheerful baby and toddler, ready to smile and speak abundantly and enthusiastically. As the challenges imposed by my mother’s mental illness mounted, there remained opportunities for joy. Until the last two years of her life, my mother also enjoyed periods when she was neither manic nor depressed. During those times, she was perceptive and supportive, someone both my closest friends and I could approach for advice and comfort, someone resembling Anne as a mother in Anne of Ingleside, who could help me recover from a friend’s betrayal or praise me for saving to give her a modest gift. As my mother’s mental condition deteriorated, I withdrew into intellectual pursuits and continued to lean on imagination, positive thinking, and social support to remain fundamentally whole.

A Year of Loss, Grief, and Mourning

Looking for external affirmation of my enduring interest in the Anne books, I wrote an American Civilization course paper about the continuing popularity of the series. My research revealed surprising and thrilling news: There were two more books in the series, Rainbow Valley and Rilla of Ingleside, which I had not known existed. A casual search for the books came up empty; they were out of print, at least in the United States.

I mentioned my fruitless search to my mother. The day I graduated from university, my parents gave me a first edition of Rainbow Valley and an early edition of Rilla of Ingleside. My mother had engaged the services of a rare-book dealer and demonstrated, for one of the last times, that she knew me better than any other person in my life. It was a delight to read new stories about my constant companion, even though Anne’s and Gilbert’s fleeting appearances in Rainbow Valley disappointed me.

Reading Rilla of Ingleside proved more satisfying because Anne’s experiences, reflections, and emotions about the First World War rendered her more present, even though that volume centres on her daughter Rilla’s coming of age. At the same time, my response to Rilla marked a sad turning point for me during an already traumatic summer, as my mother drifted in and out of delusion and talked with me about her despair and flagging will to live. Since early childhood, I had amused and comforted myself by imagining that Anne appeared to me and accompanied me through my days as both intrepid companion and surrogate mother. After witnessing Anne’s anguish when she learns of her son Walter’s death, I could no longer sustain that fantasy. I would have to tell Anne that the carnage of the First World War did not represent “a necessary sacrifice for the sake of a peaceful future,”13 but an ongoing chapter that would continue a generation later with the horrors and genocide of the Second World War. I knew it would crush her.

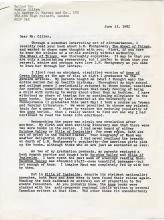

In June 1982, searching for a kindred spirit who could understand my loss, I wrote to Mollie Gillen, author of The Wheel of Things, the Montgomery biography that had revealed the existence of Rilla of Ingleside to me. I wrote:

Reading [Rilla of Ingleside] saddened me entirely out of proportion to the events recounted … . How fragile all the characters seemed in the hurricane of world events! One of my favorite childhood fantasies was that Anne Shirley (Blythe) would step from her world into mine, and I would acquaint her with the late twentieth century. I can never have that dream again, for I know that she could not survive in a profane world that has retained little of its former beauty. Perhaps Faith Meredith (Blythe?) could stand it—but not Anne.

…

I hope you understand why I found it necessary to write this letter. I have lived with Anne for so long that she is almost real for me—watching her adjust to the twentieth century was quite painful.

If you have the time to answer this with your thoughts, I would be very pleased. If not, at least the letter was written and sent—my first “fan” letter. Of course, I am a bit confused as to who(m?) I should send it—you, Maud, or Anne?14

To my amazement, Mollie Gillen wrote back, first in mid-August to let me know she needed to ponder my questions.15 Gillen’s more extensive response arrived in late November as I struggled to remain mentally present to my law studies while navigating forceful waves of early grief. Gillen posited that Montgomery herself used the Anne and Emily series as an escape and affirmed my conclusions about Anne:

LMM was perhaps the archetypal idealist, and such people are bound to bump very hard into reality when they meet with it. I think she found her escape from it by retreating into the Anne and Emily world, even though she did include reality in her treatment of World War One. She didn’t have the happy romantic life she had envisaged (who does?), but not of all of us have to face such hard realities as she did, with her husband’s melancholia (which she might have coped with better had she really been in love with him), and the troubles caused by her elder son Chester, who got into money troubles when quite young (and I am glad she died before he was eventually gaoled and disbarred for embezzlement …)

…

You are right to feel that Anne could not have survived in the late 20th century … but there are still people who find her world a comforting place to retreat into, so perhaps in a sense she has survived to this date. Certainly she has in the world of fantasy, and there are also those of us who react to natural beauty with the same inward ecstasy — which perhaps explains why these books are still in print.16

While I had a few friends and family members who could accompany me in my grief about my mother’s death that fall, Mollie Gillen was the one person in my life who understood this contemporaneous loss. Her words also gave Anne back to me, a reason to turn to the books again during the most painful season of my life.

In October, nightmares and difficulty concentrating led me to the university counselling centre. I was referred to a psychotherapist who did little more than grunt as I poured out my pain. Three sessions in, I realized I was receiving more solace from her small dog who sat on my lap. I quit and returned to coping as best I could with the resources at hand.

Emotionally spent after law-school finals, I began reading Anne of Green Gables and brought the whole series with me to Philadelphia for spring semester. I was determined to attend classes and study more regularly, but I needed extra support, especially while in the law-school building itself. While I had made a handful of friends by then, the University of Pennsylvania Law School in the early 1980s was a place sometimes hostile to the participation of women students and professors17 and filled with ambitious classmates competing to land the coveted federal judicial clerkship or a summer job offer from a corporate law firm. With a mixture of uneasy self-consciousness about needing these books from my childhood to feel comforted and defiance toward the alienating, repressive emotional norms of law school,18 I carried each book in turn into the building with me. Between classes, I found a quiet corner to read a few pages but deliberately did not hide away. My true friends, my kindred spirits, whether they had read the Anne books or not, would not judge me unkindly.

I needed somehow to integrate my mother’s death and my emotions about her illness and dying into my ongoing life. Two psychologists and bereavement researchers, George Bonanno and William Worden, describe that journey and life curriculum. According to studies conducted by Bonanno, the three most common trajectories for a grieving person are resilience, recovery, and chronic grief, with resilience the most common response. Resilient bereaved people may be sad, shocked, wounded, yet they “cope so effectively … that they hardly seem to miss a beat in their day-to-day lives.” Those on a trajectory of recovery, “suffer acutely, but then slowly pick up the pieces and begin putting their lives back together.” People living with chronic grief feel overwhelmed by the pain of their loss “and they find it all but impossible to return to their normal routine.”19

The recovery trajectory fit me most closely. A friend I met at the beginning of law school said that while I could become intellectually engaged in conversations about ideas, I also seemed crystalline and uncentred, and I exuded sadness.20 At the same time, even though my pain was severe, it was not overwhelming. Resilience surfaced when I experienced moments of joy even a few weeks after my mother died, and even though I will always be healing, not healed, from the traumatic nature of my mother’s death and last years of life.

The Tasks of Mourning

Worden outlines four tasks of mourning, which he argues need to be completed for a bereaved person to grow and develop: 1) “to accept the reality of the loss”; 2) “to work through the pain of grief”; 3) “to adjust to an environment in which the deceased is missing”; and 4) to remain “connected with the deceased but in a way that [permits] going on with life.”21 He points to several mediating factors which affect whether, how, and when the mourner moves through these tasks, emphasizing that we cannot expect everyone will grieve every death in the same way. Worden seeks to help his clients complete all the tasks of mourning, yet he is realistic that we do not return “to a pregrief state.” Even if we have regained hope and joy in our lives and settled into new roles and relationships, “[t]here is also a sense in which mourning is never finished.”22

Task 1: Accepting the Reality of the Loss

I accepted the reality of the loss, Worden’s first task, almost immediately. My mother ending her life was shocking, but not a surprise; in her final months alive, she lost more of what made life enjoyable for her, such as the ability to concentrate and read. She experienced more delusion and expressed hopelessness after endocrinology tests did not reveal a better way to treat her, since she was likely one of a significant percentage of people who do not respond to lithium, then the primary medication prescribed for people with bipolar disorder.23

Even so, her complete absence from my life felt like a new, abrupt, complete chasm. Within an hour of her death, I briefly saw her lying on her hospital bed, an image burned deeply into my memory. Further, the Jewish practice of each mourner shovelling dirt onto a loved one’s coffin to culminate the burial service brings the reality of death powerfully home. However, approaching Worden’s other three tasks of mourning would be far more daunting and protracted.

On Bonanno’s recovery trajectory, reading the Anne series was one way I began addressing Worden’s tasks of feeling the pain of the loss, adjusting to my environment without my mother’s presence, and searching for a new connection with her as my life moved on from her tragic death. Without a therapist to guide me, I unintentionally engaged in self-directed developmental and clinical bibliotherapy by reading the series a few months after my mother’s death. While there is debate about the efficacy of bibliotherapy as proved by clinical studies, counsellors continue to find it useful.24 Developmental bibliotherapy assists with “normal development,” facilitates expression of feeling, and helps “develop problem-solving skills” about common life issues. Clinical bibliotherapy is usually directed by a professional and addresses more severe emotional issues.25

I partook of the identification and catharsis stages of bibliotherapy, as outlined by Amy Catalono.26 Identifying with Anne’s sadness helped me feel less alone in my strong feelings. The well-worn scenes gave me solace, punctuated by powerful crying as I grieved along with Anne when her adoptive/spiritual father Matthew, her newborn baby Joyce, and her son Walter die. This reading was a profoundly emotional experience; because the details of plot and character felt deeply familiar to me, I could surf the waves of emotion coming from the books and bring my battered nervous system to them.

At the same time, reading these familiar volumes diverted my attention from grief, allowing me to toggle back and forth between distraction and engagement. Bereavement researchers Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut have developed a “dual process model” of coping with bereavement to explain the cognitive processes that enable coping. Their analyses assert that oscillating between confronting the loss and distraction from or even avoidance of grief is an adaptive approach.27 While Worden claims that anything enabling a person to avoid the pain of grieving prolongs mourning, he also concludes this dual process model is not “antithetical to the tasks of mourning. The tasks of mourning need not be worked on in linear fashion but can be revisited and reworked intermittently over time.”28 Deciding to focus more on my studies and less on grieving, partly with the aid of Anne, did prolong my mourning, which remained partially unresolved until I returned to it more fully in my thirties and forties. At the same time, reading Anne allowed me to touch that pool of grief at a time I had almost no external support to delve more deeply.

Reading the series in these past months to write this article, I can see how certain vignettes, scenes, and passages spoke to me as I not only grieved my mother’s death but also began healing from years of living with a mother whose mental illness profoundly shaped my daily life. This incipient healing was completely intertwined with my journey through Worden’s tasks of mourning. Anne’s emotions, sorrows, grief, and wisdom gave me food for this journey. In the next sections, I juxtapose resonant passages from the Anne series with memories of my experience.

Task 2: Working Through the Pain of Grief (and Tragedy)

Like so many people in severe grief, I wondered and worried about whether I was normal. Reading Anne reassured me; she is a protagonist valorized for her strong emotion at times of grief. She “we[eps] her heart out” after going to bed the night Matthew dies.29 When their housekeeper, Susan Baker, brings Anne and Gilbert their dead baby Joyce, Anne is “broken, tear-blinded.”30 She recovers slowly, weak and physically ill after Joyce’s and Walter’s deaths. In the first days after my mother’s death, I had never before cried so frequently or forcefully. I tried to help with the telephone calls informing family and friends of her death and inviting them to the funeral, but I barely finished the first sentence before my sobs rendered me incoherent. Instead, with the help of my mother’s friends, I quietly, slowly cleaned and prepared the house for visitors, taking breaks to wrap my body around a slim tree in the front yard. During the first Shiva service, I collapsed in tears and had to be carried to bed.

As a girl Anne will not be deterred from expressing strong feelings. When she learns that the Cuthberts have not intended to adopt her, she announces she will burst into tears and does. That night, she again insists on her emotional reality when Marilla says “good night” and Anne replies it is “the very worst night I’ve ever had.” Thinking Mrs. Barry will continue to forbid her to see Diana after the currant wine incident, Anne laments, “I must cry … My heart is broken.”31 When Marilla tries to console Anne after newborn Joyce’s death with talk of it being “God’s will,” Anne refuses to agree on either emotional or theological grounds.32 I had suppressed expressing any strong emotion, especially in front of my parents, to protect my tender self from my mother’s volatility. Anne’s behaviour contrasts with what had been for me an increasingly muted adolescence. Anne lives out her nature as “all ‘spirit and fire and dew.’”33 Could I live closer to that way of being someday?

Like many survivors of a family suicide, my response to my mother’s death included anger at her. Anger often tinges the young Anne’s sadness or hurt.34 In Anne of Ingleside, Olivia Kirk thanks Clara Wilson for her public, truthful, and rageful accounting of Peter Kirk’s behaviour when speaking at his funeral, a nod toward the complicated feelings that may come in the wake of any death. Anne thinks the situation heartbreaking, but unlike others who attended the funeral, she does not criticize Clara Wilson’s angry speech.35 Like many bereaved people, I also harboured fear about who might die next; in my case, my father’s weight and smoking frightened me. When Jem announces that he plans to enlist, both Anne and Gilbert remember the day their first-born, Joyce, died. When Shirley says he wants to enlist, Anne reflects on both Joyce’s and Walter’s deaths.

Sights, smells, sounds, and objects associated with a death linger uneasily in memory. In the moment when Anne sees Matthew fall and die, she is carrying white narcissi. “It was long before Anne could love the sight or odor of white narcissus again.”36 News of my mother’s major suicide attempt a couple of years before her death came to me by telephone. The morning of the day my mother died, my father found her in a coma. He shouted my name to awaken me from sleep in my childhood bedroom. Tests later that day revealed she had taken an overdose of Tylenol. It was many years before my startle reaction began to ease if I received a telephone call at an odd hour or any sound awakened me from sleep. It is only recently I have begun to take Tylenol again as a pain reliever.

Would I be unable to emerge from sorrow for more than a moment, a day at a time? Identifying with Anne’s grief after major losses was a safer entry point for my almost overpowering sadness. Her repeated emergence from loss, even if it changes her,37 gave me a glimpse of my own future. Seeing that peacefulness, even joy, comes again gave me courage to withstand grief. For example, the morning after her first terrible evening at Green Gables, Anne says the world does not seem “such a howling wilderness as it did last night,” notices her surroundings are beautiful, with “scope for imagination,” and decides she will enjoy the drive to Mrs. Spencer’s, which Anne expects will end with her return to the orphan asylum.38 In my own life, a week after my mother died, I noticed the intense colour of a sunset on a country road near my home, surprised I could appreciate its radiance.

After Matthew’s death, Anne tells Mrs. Allen, one of the kindred spirits who populate the series, that she is surprised to find she still finds beauty and can laugh. Mrs. Allen advises her not to “shut our hearts against the healing influences that nature offers us,” and then says she understands why Anne believes she should not feel happy.39 Would I find more than one or two kindred spirits who could hold my complicated past and emotions with me? Most of the two hundred people who came to our home during our initial days of mourning opened a conversation with me by saying they “were sorry,” then asking me about law school. I kept one of my two best friends at my side to give me an excuse to leave unhelpful conversations. Most people did not know how to respond to the magnitude of my loss; they backed away; they wanted me not to have changed forever. One of my two guardian angels from the week of Shiva altered her post-graduation plans to move to Philadelphia and support me emotionally. I experimented with confiding in law-school acquaintances and then went mostly silent about my mother’s death. It was too heavy a burden for new relationships to bear.

Anne’s experiences both as a bereaved person and friend to people experiencing loss provided me hope. When Anne confides to Katherine Brooke about her early years as a servant foster child and orphan asylum resident, Katherine feels close to Anne for the first time.40 Leslie Moore feels able to tell Anne her own calamitous story only after Anne’s baby dies. Anne responds to Leslie’s tragedy by declaring she feels uniquely close to her.41 In the wake of tragedy, relationships change, and the change can be positive as well as negative.

Task 3: Adjusting to an Environment in Which the Deceased Is Missing

In our family constellation before my mother’s death, only she could express strong feelings. There were consequences for the rest of us if we did so: a cutting remark, a reminder of her sacrifices to earn money via a mostly unfulfilling career as a teacher, a screaming tantrum. After my mother died, I began a decades-long shift toward more emotional transparency. Anne models that transparency. When Anne begins to cry after learning the Cuthberts do not plan to adopt her, Marilla says, “there’s no need to cry about it.” Anne argues that Marilla would cry too in Anne’s situation.42 Wendy Shilton identifies this moment as the key transformative exchange in their relationship: “Anne, who knows and has the power to name emotion, has the strength to admit what others cannot: that core embodied needs are the forces that drive and sustain life and growth.”43 Transformation indeed. When Matthew dies and Marilla hears Anne crying during the night, she awkwardly tries to comfort Anne and then tells her for the first time that she loves her.44

After a few months in which I simply left the classroom if I felt too sad or weepy, once I returned to law school for the second semester, I decided to reimpose more emotional restraint to focus better on my studies. Anne provides examples for this approach as well. After Matthew is buried, Anne’s life carries on but with “an aching sense of ‘loss in all familiar things.’”45 With their loved ones away fighting in the First World War, Anne comforts their housemate Gertrude Oliver, saying it is natural to think things cannot go on as usual “when some great blow has changed the world for us.”46 Anne understands that part of adjusting amidst grief is, somehow, to return to life goals.

The arrival of my first-semester grades confirmed another milestone. I would not be a top student. Instead of disappointment, I felt gratitude that I had escaped academic probation and almost giddy with freedom. I could approach student life more casually, with different priorities. I no longer needed to please my mother, who had been living through my academic success. I enjoyed this new outlook, while retaining a full measure of grief over her death. Anne articulates a similar nuanced sentiment when her son Jem is born, and she corrects Marilla, who says he “will take Joyce’s place.” Anne responds, “nothing can ever do that. He has his own place, my dear, wee man child. But little Joy has hers, and always will have it.”47

Task 4: Find a Connection with the Deceased While Beginning a New Life

Some months after my mother died, my father asked me to help him clear out her closets and drawers. I took several pieces of my mother’s clothing to feel connected to her by wearing them and because they carried the scent of her perfume, Tabu, which she wore every day. While Anne does not have that option, she visits the house where her parents once lived and eagerly receives some letters her parents wrote to each other. During her childhood, when Diana’s mother forbids her to see Anne, Anne cuts a lock of Diana’s hair to remember her. Anne demonstrates the power of objects to maintain connection.

I worried about how I would keep a relationship with my mother for the remainder of my own life. Anne does so through both intentional action and unbidden thoughts. She brings flowers to Matthew’s grave frequently while she lives in Avonlea, on visits home, and at turning points in her life. Both Anne and her elderly friend Captain Jim assert a relationship based on memory can last forever: Anne will always remember Matthew’s love and kindness. Captain Jim will never forget Lost Margaret, and he predicts that Anne would not forget him.

Even more worrisome, would I unearth the happy memories of my mother? There were plenty to find, but the last two years of her life had ranged from difficult to horrible, obscuring what came before. For me, forging a connection with my mother meant recovering memories of her in times when she was neither manic nor depressed. For this reason, the story of Summerside resident Mr. Armstrong not being able to remember what his dear son Teddy looked like, even a few days after Teddy’s sudden death from pneumonia, always affected me deeply. Mr. Armstrong’s torment lifts when Anne and her student Lewis visit unannounced with a photograph of Teddy they have taken weeks prior, before Teddy fell ill.48 A few days after my mother died, I called a childhood friend to try to jump-start my positive memories by asking for hers, but her descriptions felt like they came from an alien world. Reading a magazine in a coffee shop that winter was my Mr. Armstrong moment. The story referred to a celebrity mother and daughter holding hands. Images of the many times my mother and I had done the same flooded my consciousness. That moment opened the gateway to a more complete picture of my past.

Reading the Anne series did not heal my grief. The books accompanied me at the beginning of a long journey that will likely never end. Anne’s wisdom did not touch the guilt and shame that accompanied me, as these emotions often do with family survivors of suicide.49 I could not integrate some of Montgomery’s wisdom. For example, I could not reframe my sorrow as a “sanctifying touch”50 because, while my life was utterly changed by my mother’s death, it took years for me to grieve without unwarranted guilt and shame depriving my sorrow of its emotional and spiritual growth. I was not yet ready to hear my grief would transform over time, as Captain Jim tells Anne.51 Bibliotherapy alone would take me only so far. I did not touch the deeper wounds I carried until more than eight years later, when I began three years of weekly psychotherapy. About the tasks of mourning, Worden says, “’[t]asks can be revisited and reworked over time … Grieving is a fluid process.”52

How Montgomery Has Shaped Me as a Rabbi Chaplain

Almost forty years later, I have left the practice of law, reconnected with my girlhood spiritual and religious self, received ordination as a rabbi, worked for fifteen years as a chaplain, and served as the director of a hospital-based spiritual care service. Reading the Anne series now, I realize some of my philosophy and practices as a chaplain I first learned from Anne. While attending Redmond College, Anne and Gilbert talk about sorrow in life and Anne speaks of the cup of bitterness everyone must drink someday.53 Everyone experiences suffering; what matters is our response to it. Katherine Brooke and Leslie Moore, during their years of hardship, serve as cautionary tales.54 If we turn away from people who could bring solace and support, loneliness intensifies our suffering.

The field of narrative medicine recognizes that our ability to formulate and tell stories brings healing.55 When Marilla tells Anne her hair will not likely to turn auburn as she grows up, Anne recites a line she learned in a book, saying her “life is a perfect graveyard of buried hopes.”56 Anne can stand outside herself and reflect on her life as a story, even if it is the melodramatic rendering of a child. This narrative ability adds to her resilience. Once Katherine and Leslie confide in Anne, they are transformed by telling her their stories. They both experience adult friendship with an age peer for the first time.

When Anne and her student, Paul Irving, encounter each other as they place flowers, Anne on Matthew’s grave and Paul in a spot near his grandmother’s grave to represent his mother’s faraway burial site, Paul tells Anne his mother’s death hurts as much as it did when she died three years ago. Anne affirms Paul’s feelings; she does not tell him to move on.57 She allows people to grieve on their own schedule.

After talking with Leslie about Owen Ford’s departure and Leslie’s ensuing anguish, Anne reflects and castigates herself for giving a well-meant speech when she dislikes them.58 In the wake of Walter’s death, several people speak clumsily to Rilla when silent, sympathetic accompaniment is more appropriate.59 Anne’s and Rilla’s distress helped teach me to avoid speeches that offer hackneyed comfort when talking to someone about their loss.

Finally, after receiving news from Jem that he has survived a battle involving poison gas, Anne reflects on the preciousness of laughter, saying it is sometimes “as good as a prayer.”60 When my patients or their loved ones are able to find respite in humour, I savour the moment with them.

Reading Anne and Grappling with Montgomery as a Person

I read the Anne books again during these past eighteen months, plus Chronicles of Avonlea, Further Chronicles of Avonlea, and The Blythes Are Quoted for the first time. I came to these texts having read some of the recent Montgomery scholarship and having attended the 2018 L.M. Montgomery and Reading Conference in Charlottetown. New awareness enriched and shadowed my reading. Montgomery wrote the Anne books, in part, as a reliable source of income for her family. Rainbow Valley and Anne’s House of Dreams were written to encourage Canadians at war.61 The horrors of the Second World War shattered Montgomery’s illusions about the sacred purpose of the First World War.62 Controversy attends the cause of Montgomery’s sudden, untimely death, with some evidence she may have ended her own life.63 A more pessimistic, sad Montgomery64 read over my shoulder as I reconnected with Anne’s joy-tinged wisdom. Like Montgomery, I see the subtleties in how life unfolds now in a way that was impossible to see in my twenties.

Montgomery’s prejudices also struck me with more force, causing me to question how or even whether I can continue to value these texts. While the anti-Semitic rendering of the Jewish peddler who sells an unwitting young Anne hair dye that turns her hair green always troubled me, I now read more critically and painfully Montgomery’s Anglo-centred colonialist, classist depictions of Acadians and poor children brought to Canada from London, her ubiquitous depiction of people occupying a set place in a stratified society.65 I noted her almost complete erasure of First Nations people from Anne’s life, particularly the Mi’kmaq, who would have been visible in Prince Edward Island during her time.66 I cannot wish away my criticism by saying she was a woman of her time because there have always been people, even white people, who resisted white supremacy and colonialism, but Montgomery was not one of them.

I also cannot say there is an unbridgeable chasm between her and me, because some of the bias she freely expressed in her writing lives on in me implicitly. The nauseous dismay I felt reading the short story “Tannis of the Flats,” which portrays Tannis as being from an inferior race,67 or references to Squaw Baby in “The Cheated Child,”68 are a cousin to the sick feeling that arises in me when one of my own inner white-supremacist voices emerges in my consciousness, or I realize I have handled an interaction based on an assumption rooted in bias, not fact. I will never read those two stories again; they are not redeemable for me. However, I do not regret having read them, and my continued reading of Montgomery allows me to reflect on how my beloved author was part of my socialization as a “white”-skinned person with prejudices I continue to unearth and try to counter. The next time I read any of the Anne books, I plan to continue bringing the critical eye of what Philip Nel refers to as “reflective nostalgia,”69 to see white supremacy being constructed or maintained, even while I appreciate Anne’s wisdom.

Conclusion

In Rilla of Ingleside, Anne says life has been cut in two by the chasm of the war.70 As I read the Anne series in 2020 and 2021, like so many others, I lived through a pandemic, reckoned with long-standing and present racial injustices, and endured the wildfires that threatened most of Santa Cruz County, California, where I live and that menace us anew each year. Grief and tragedy peered around every corner. Anne continued to give me comfort and models of resilience. Once again, I engaged in bibliotherapy.

Healing is an iterative, spiralling process. Through that lifelong process, I will carry Anne with me, whether I know it consciously or not. Looking back at the Anne series and its role in the most challenging year of my life has brought me to a new narrative, a deepening peace.

About the Author: Lori Klein is a rabbi and health care chaplain at Stanford Health Care and Montage Health Care. She holds an M.A. in the History and Sociology of Science and a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. Her essay, “Cultural Humility and Reverent Curiosity: Spiritual Care with and Beyond Norms,” appears in Postcolonial Images of Spiritual Care: Challenges of Care in a Neoliberal Age (edited by Lartey and Moon, Wipf and Stack, 2020). An essay she co-authored with several staff chaplains, “Spiritual Care in the Shadow of Loss and Uprising: A Year in the Life of a Team,” will be published as part of Volume 2: Postcolonial Practices of Spiritual Care: A Project of Togetherness during COVID-19 and Racial Violence (edited by Lartey and Moon, Wipf and Stack, 2022). She has lectured on resilience, cultural humility, religion, and spirituality in the United States and Central Europe. Facebook handle: Lori Klein. LinkedIn handle: Lori Klein.

- 1 Montgomery, BAQ 480.

- 2 Guinier, “Becoming Gentlemen” 4, 45–46.

- 3 Worden, Grief Counseling 27–37.

- 4 Bode, “Anguish of Mother Loss” 55.

- 5 Ross and Warnqvist, “Reading L.M. Montgomery.”

- 6 This is discussed by Robinson, “Bosom Friends” 20–21, 24–26.

- 7 Ross and Warnqvist.”

- 8 Connor-Smith and Flachsbart, “Personality and Coping.”

- 9 Connor-Smith and Flachsbart.

- 10 Connor-Smith and Flachsbart.

- 11 Montgomery, AGG 36.

- 12 Montgomery, AWP 29, 37, 39, 137–45.

- 13 Lefebvre, Introduction, BAQ xvi. Referring to Anne’s final words to Jem after reading Walter Blythe’s poem “The Aftermath” and Anne’s poem “Come, Let Us Go” in The Blythes Are Quoted, Lesley Clement concludes that Montgomery expresses Anne’s and Montgomery’s inability to regain emotional resilience when faced with the apparent futility of the First World War and the horrors of the Second World War. Clement, “From ‘Uncanny Beauty,’” 58–61.

- 14 Klein, personal correspondence, 15 June 1982.

- 15 Gillen, personal correspondence, 19 August 1982.

- 16 Gillen, personal correspondence, 21 November 1982.

- 17 Guinier 51–52, 58–59. While Guinier’s article was based on studies conducted in the early 1990s at University of Pennsylvania’s Law School, my experiences in the early to mid-1980s were the same or even more challenging. For example, on the last day of my first year Civil Procedure class, some of the male students paid for a stripper to entertain the students and male professor.

- 18 Guinier 43–44, 47, 49, 71.

- 19 Bonanno, The Other Side.

- 20 Marks, telephone conversation, 26 June 2021.

- 21 Worden 27–37.

- 22 Worden 37–47.

- 23 Salk Institute, “New Clues”; Calabrese and Bowden, “Lithium and the Anticonvulsants.”

- 24 Pehrsson and McMillen, “Bibliotherapy: Overview.”

- 25 Catalano, “Making a Place” 17–18.

- 26 Catalano 18–19.

- 27 Stroebe and Schut, “Meaning Making” 56, 59–60.

- 28 Worden 30–31, 37.

- 29 Montgomery, AGG 287.

- 30 Montgomery, AHD 125.

- 31 Montgomery, AGG 23, 27, 125.

- 32 Montgomery, AHD 126.

- 33 Montgomery, AGG 174.

- 34 For examples, Montgomery, AGG 23, 27, 45, 63–64, 98, 123–24.

- 35 Montgomery, AIn 191–95.

- 36 Montgomery, AGG 285.

- 37 For examples, Montgomery, AHD 128, RI 351–52.

- 38 Montgomery, AGG 29, 31, 36.

- 39 Montgomery, AGG 28—89.

- 40 Montgomery, AWP 143–44.

- 41 Montgomery, AHD 13—37.

- 42 Montgomery, AGG 23.

- 43 Shilton, “Centre and Circumference” 127–28.

- 44 Montgomery, AGG 287–88.

- 45 Montgomery, AGG 288.

- 46 Montgomery, RI 228.

- 47 Montgomery, AHD 205.

- 48 Montgomery, AWP 125–26, 129–31.

- 49 Worden 119–21.

- 50 Montgomery, AGG 284.

- 51 Montgomery, AHD 129–30.

- 52 Worden 32, 37.

- 53 Montgomery, AIs 56–57.

- 54 Montgomery, AWP 142–45; Montgomery, AHD 134–35.

- 55 Charon, Narrative Medicine 180–82.

- 56 Montgomery, AGG 36–38.

- 57 Montgomery, AA 162–63.

- 58 Montgomery, AHD 168.

- 59 Montgomery, RI 254–55.

- 60 Montgomery, RI 141–42.

- 61 Epperly, Afterword, BAQ 512.

- 62 Montgomery, BAQ 477, 510; Lefebvre, “‘Abominable War’” 113, 119–20, 122–23.

- 63 Lefebvre, Introduction, BAQ x-xi; Rubio, “Uncertainties” 45–61.

- 64 Fiamengo, “Shadows of Depression” 170–78.

- 65 Jones, “‘Nice Folks’” 133–46; Mitchell, “Civilizing Anne” 154–58.

- 66 Collins-Gearing, “Stolen Ground” 167–69.

- 67 Montgomery, FCA 280–301.

- 68 Montgomery, BAQ 297–311.

- 69 Nel, “Breaking Up.”

- 70 Montgomery, RI 208.

Works Cited

Bode, Rita. “L.M. Montgomery and the Anguish of Mother Loss.” Storm and Dissonance, edited by Jean Mitchell, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008, pp. 50–66.

Bonanno, George A. The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Loss Tells Us About Life After Loss. E-book edition. Basic Books, 2019. Kindle.

Calabrese, Joseph R., and Charles Bowden. “Lithium and the Anticonvulsants in Bipolar Disorder.” American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 2000, https://www.acnp.org/g4/GN401000106/CH.html.

Catalano, Amy. “Making a Place for Bibliotherapy on the Shelves of a Curriculum Materials Center: The Case for Helping Pre-service Teachers Use Developmental Bibliotherapy in the Classroom.” Education Libraries: Children's Resources, vol. 31, no. 1, Spring 2008, pp. 17–22.

Charon, Rita. Narrative Medicine: Honoring the Stories of Illness. Oxford UP, 2006.

Clement, Lesley. “‘From ‘Uncanny Beauty’ to ‘Uncanny Disease’: Destabilizing Gender through the Deaths of Ruby Gillis and Walter Blythe and the Life of Anne Shirley.” L.M. Montgomery and Gender, edited by E. Holly Pike and Laura M. Robinson, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2021, pp. 44–67.

Collins-Gearing, Brooke. “Narrating the ‘Classic’ on Stolen Ground: Anne of Green Gables.” Ledwell and Mitchell, pp.164–78.

Connor-Smith, Jennifer K., and Celeste Flachsbart. “Relations Between Personality and Coping: A Meta-Analysis.” Faculty Publications–Grad School of Clinical Psychology. 103, https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1102&context=gscp_fac.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. Afterword. Montgomery, The Blythes Are Quoted, pp. 511–16.

Fiamengo, Janice. “‘… the refuge of my sick spirit …’: L.M. Montgomery and the Shadows of Depression.” The Intimate Life of L.M. Montgomery, edited by Irene Gammel, U of Toronto P, 2005, pp. 170–86.

Gillen, Mollie. Personal correspondence. 19 August 1982.

---. Personal correspondence. 21 November 1982.

Guinier, Lani, Michelle Fine, and Jane Balin. “Becoming Gentlemen: Women’s Experiences at One Ivy League Law School.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, vol. 143, no. 1, pp. 1–110.

Jones, Caroline E. “‘Nice Folks’: L.M. Montgomery’s Classic and Subversive Inscriptions and Transgressions of Class.” Ledwell and Mitchell, pp. 133–46.

Klein, Lori. Personal correspondence. 15 June 1982.

Ledwell, Jane, and Jean Mitchell, editors. Anne Around the World: L.M. Montgomery and Her Classic. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2013.

Lefebvre, Benjamin. Introduction. Montgomery, The Blythes Are Quoted, pp. ix-xvii.

---. “‘That Abominable War!’: The Blythes are Quoted and Thoughts on L.M. Montgomery’s Late Style.” Storm and Dissonance: L.M. Montgomery and Conflict, edited by Jean Mitchell, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2008, pp. 109–30.

Marks, Pamela. Telephone conversation. 26 June 2021.

Mitchell, Jean. “Civilizing Anne: Missionaries of the South Seas, Cavendish Evangelicalism, and the Crafting of Anne of Green Gables.” Ledwell and Mitchell, pp. 147–63.

Montgomery, L.M. Anne of Avonlea. 1909. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Condensed and abridged by Mary W. Cushing and D.C. Williams, illustrated by Robert Patterson. Grosset and Dunlap, 1961.

---. Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970

---. Anne of Ingleside. 1939. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Anne of the Island. 1915. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Anne of Windy Poplars. 1936. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Anne’s House of Dreams. 1917. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Chronicles of Avonlea. 1912. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Further Chronicles of Avonlea. 1953. Grosset and Dunlap, 1970.

---. Rainbow Valley. Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1919.

---. Rilla of Ingleside. 1921. Grosset and Dunlap, 1921.

---. The Blythes Are Quoted. Penguin Random House Canada, 2018.

Nel, Philip. “Breaking Up with Your Favorite Racist Childhood Classic Books.” The Washington Post, 16 May 2021, https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2021/05/16/breaking-up-with-racist-childrens-books/.

Pehrsson, Dale-Elizabeth, and Paula McMillen. “Bibliotherapy: Overview and Implications for Counselors.” Professional Counseling Digest, ACAPCD-02, American Counseling Association, https://www.counseling.org/resources/library/ACA%20Digests/ACAPCD-02.pdf.

Robinson, Laura. “Bosom Friends: Lesbian Desire in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne Books.” Canadian Literature 180, Spring 2004, pp. 12–28.

Ross, Catherine Sheldrick, and Åsa Warnqvist. “Reading L.M. Montgomery: What Adult Swedish and Canadian Readers Told Us.” Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, 13 May 2020, https://journaloflmmontgomerystudies.ca/reading/rosswarnqvist.

Rubio, Mary Henley. “Uncertainties Surrounding the Death of L.M. Montgomery.” Ledwell and Mitchell, pp. 45–62.

Salk Institute. “New Clues Why Gold Standard Treatment for Bipolar Disorder Doesn’t Work for Majority of Patients.” Neuroscience News.com, 5 January 2021, https://neurosciencenews.com/lef1-bipolar-lithium-17536/.

Shilton, Wendy. “Anne of Green Gables as Centre and Circumference.” Ledwell and Mitchell, pp. 120–30.

Stroebe, Margaret S., and Henk Schut. “Meaning Making in the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement.” Meaning Reconstruction and the Experience of Loss, edited by Robert Neimeyer. American Psychological Association 2001, pp. 55–73.

Worden, J. William. Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner. Third Edition. Springer Publishing Company, 2002.