Abstract: This essay recovers a “doubleness” or “second and more difficult poem” that exists beneath the surface of the only Great War poem that L.M. Montgomery published during her lifetime. Using Montgomery’s wartime journals, as well as her war novel Rilla of Ingleside, this analysis suggests that “Our Women” is a complex text that simultaneously voices patriotic sentiments as it subverts the traditional elegy and exposes the emotional traumas Montgomery and other women endured during the Great War and in its aftermath.

Although best known for her fiction,1 L.M. Montgomery was first published as a poet. In November 1890, just shy of her sixteenth birthday, “On Cape Le Force” was published in Charlottetown’s Daily Patriot. Montgomery published over five hundred poems during her lifetime; however, few have received careful attention and analysis. Shortly after The Poetry of Lucy Maud Montgomery was published in 1987, Eileen Manion reviewed the volume in The Montreal Gazette, writing, “Although she wrote poems meant for ordinary readers, not for other poets or literary scholars, today they will probably appeal only to hard-core Montgomery fans or those professionally interested in Canadian literary history.”2 Montgomery’s poetry is, nevertheless, a rich resource for those interested in women’s emotional lives and therefore merits reconsideration and close reading.

Middle-class North American social and cultural norms at the turn of the twentieth century constrained the full and honest expression of human emotion, including women’s displays of grief during war. “Our Women” is the only poem Montgomery published during her lifetime that explicitly addresses the First World War.3 In its three short stanzas, Montgomery describes three women, each of whom is grappling with the emotional effects of war. When read in the context of Montgomery’s other war writings,4 specifically her journals and the novel Rilla of Ingleside, “Our Women” reveals itself to be a complex work that exposes the mental trauma that women endured as they managed competing ideas and identities: The poem voices patriotic sentiments while it lays bare the tremendous sacrifices that Canada asked of its women during the Great War.

Montgomery’s Poetry

Montgomery published only one collection of poetry during her lifetime. Dedicated “To the memory of the gallant Canadian soldiers who have laid down their lives for their country and their Empire,”5 The Watchman and Other Poems appeared in 1916. None of the poems included in the volume directly refers to the war that had come to obsess Montgomery’s life and journal writings. One reviewer assured readers that it was “not a book of war poems; it is a ‘book of life,’” and the Toronto Globe described it as a “volume full of charming things” that expresses “a gentle sympathy with the varying moods of nature,” while the Edinburgh Scotsman declared it a “breezy and inspiriting book.”6 Many of the poems included in The Watchman had been previously published before the war, and the book’s sections were titled “Songs of Sea,” “Songs of the Hills and Woods,” and “Miscellaneous.” Susan Fisher observes that at a time when many authors were eager to write about the war, Montgomery was less concerned with publishing a topical book than she was with managing her reputation and showcasing “her achievements as a poet.” Fisher further notes that Montgomery’s complex and evolving views of the war would have been challenging to wrestle into the traditional form and diction of the poetry she aspired to write.7 In a letter to G.B. MacMillan written in 1903, Montgomery confided, “I know that I touch a far higher note in my verse than in prose,”8 and, accordingly, her poems in The Watchman display strong influences of the British Romantic and Victorian writers she loved. Yet even at the time of its publication, The Watchman was much less successful than her novels, and today it receives scant attention other than being dismissed for what is now viewed as its outdated form and content, in Fisher’s words, its “banal spirituality and outmoded classicism.”9

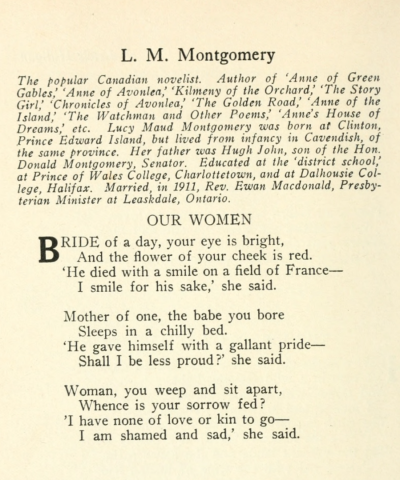

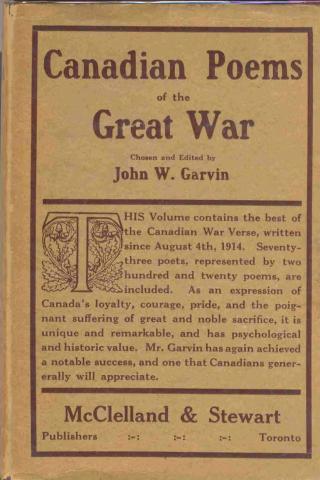

While certain poems in The Watchman may obliquely or metaphorically allude to the war that consumed Montgomery’s attention from 1914 to 1918, “Our Women”—a poem that directly addresses the sacrifices women were asked to bear during the war—does not appear in the volume. It was published two years later in John W. Garvin’s Canadian Poems of the Great War (1918).10 In the foreword to the anthology, Garvin asserts the significance of his collection: “As the poetic expression of a young nation, involved for the first time in a life and death struggle, it is unique and has psychological and historic value.”11 Scholars have not examined many of the poems in the anthology for their psychological and historic value, including “Our Women.” As Andrea McKenzie and Jane Ledwell write in their introduction to L.M. Montgomery and War, “In the larger realm of Canadian war scholarship—especially literary scholarship—Montgomery is rarely considered.”12 Even in Fisher’s excellent analyses of Montgomery’s war poetry (including poems published posthumously), the three stanzas of “Our Women” receive only brief mention, characterized as “pat vignettes.”13

Doubleness and Buried Doubt

Why has Montgomery’s poetry been so consistently overlooked? Victorian literature scholar Isobel Armstrong argues that, too often, readers and critics do not look beneath the literal surfaces of women’s writing and so miss its “doubleness,” in which “conventions are subjected to investigations, questioned, or used for unexpected purposes. The simpler the surface of the poem, the more likely it is that a second and more difficult poem will exist beneath it.”14 Although numerous critics have recognized the doubleness that characterizes Montgomery’s prose, few scholars have searched her poetry for the “second and more difficult” text that lies beneath or looked for the subtle challenges and evasions in her poems that so often characterize her prose writing. If “Our Women” is read with an eye to identifying what Irene Gammel explains is the author’s “hallmark equivocation, trying to accommodate two contradictory positions at once,”15 what insights might be gained?

Thomas Vincent explains that Canadian poetry of the First World War often exhibits patterns of “ambivalence and evasion” underpinned with “a buried element of doubt,” for Canadian writers struggled to reconcile private despair about war with the public need to defend it and the “myth of nation building that was so central to Canadian expectation and the sense of national purpose at this stage.”16 Furthermore, Joel Baetz writes in Battle Lines: Canadian Poetry in English and the First World War that “no one has approached patriotic poetry as a complex management of competing ideas and identities, resolved [by force of desire] into coherence.”17

Significantly, as Janet Montefiore argues in “‘Shining Pins and Wailing Shells,’” women poets of the First World War faced additional constraints and tensions, as they were “bounded” and “governed” by conventional gender roles that expected them to conform to norms of patriotism and traditional verse. They therefore often felt “trapped,” powerless to affect the course of the war, to resolve their persistent anxiety for the men they loved, or to escape the constraints of “the Victorian and Georgian poetic tradition, itself deeply imbricated with patriotic ideology and overwhelmingly masculine in its assumptions.” Montefiore concludes that while the surfaces of women’s war poems frequently “assent to the tenets of the War,” a closer reading reveals that women’s war poetry often expresses an “ambivalence with which even very patriotic women could write, manifesting not only gratitude and pity, but envy, guilt, awareness of their own power, and even buried rage.”18 Jane Dowson makes a similar point in Women, Modernism and British Poetry, 1910–1939, stating that women war poets frequently disguise their “gendered perspective with the impersonality of universal voices and conventional forms, but there is often an unofficial discourse below the respectable, symbolised, textual surface.” Commenting on the war writings of Frances Cornford and Vita Sackville-West, Dowson observes, “there is often a personal undertow to the superficially tame writing. Although they did not voice feminist protest, they investigated social conventions, notably concerning marriage and motherhood.”19 The same can be said of the war writings of Montgomery.

The doubleness and complexities of “Our Women” are highlighted when the poem is viewed in the context of Montgomery’s journals and her war novel, Rilla of Ingleside (begun in February of 1919 and published in 1921).20 Here is the poem as it was published in 1918:

Our Women

Bride of a day, your eye is bright,

And the flower of your cheek is red.

‘He died with a smile on a field of France—

I smile for his sake,’ she said.

Mother of one, the baby you bore

Sleeps in a chilly bed.

‘He gave himself with a gallant pride—

Shall I be less proud?’ she said.

Woman, you weep and sit apart,

Whence is your sorrow fed?

‘I have none of love or kin to go—

I am shamed and sad,’ she said.

As the title makes clear, the women described in the poem belong neither to themselves nor to their families, but to the nation. The phrase “Our Women” parallels that of “Our Boys,” a term frequently applied to soldiers. In this way, the title of the poem subtly suggests that women’s sacrifices may be compared to those of enlisted men. In her essay “Writing War Poetry Like a Woman,” Susan Schweik contends that women writers of the First World War did not possess the “imaginative right to the voice of the soldier”;21 however, numerous women’s poems link the heroism of death in battle with women’s sacrificial grief (for example, poems such as Dorothy Parker’s “Penelope,” Charlotte Mew’s “May, 1915,” and Violet Gillespie’s “Portrait of a Mother”).22 In her essay “‘Great Expectations’: Rehabilitating the Recalcitrant War Poets,” Gill Plain demonstrates that many war posters of the period also sought to persuade the public that “those who sacrificed a loved one to the cause were equally heroic.”23

A key scene in Rilla of Ingleside underscores that women’s sacrifices are comparable to those of enlisted men. Upon learning that her brother Walter has enlisted to fight, Rilla cries to her mother, Anne, “Our sacrifice is greater than his … Our boys give only themselves. We give them.”24 It is a bold claim. In 1915, British feminist, pacifist, and journalist H.M. (Helena) Swanwick wrote, “War is waged by men only, but it is not possible to wage it upon men only. All wars are and must be waged upon women and children as well as upon men.”25 Laura M. Robinson writes that in Rilla, “The home is akin to a battlefield. Thus, Montgomery revises an understanding of heroism to include women’s domestic lives.”26 Montgomery’s focus on narrating women’s home-front war experiences in “Our Women” highlights women’s suffering and sacrifice as it expresses a conflicted view of patriotism.

Disguised Grief and Trauma

With its title “Our Women” subtly linking men’s and women’s participation in the war, Montgomery suggests that men’s and women’s experiences may be compared, raising the possibility that women, too, experienced mental trauma—the civilian equivalent of shell shock. Suzie Grogan’s study of shell shock notes that “from its earliest published description in The Lancet in 1915, [the designation] has always been a cultural rather than a medical construct,” and she argues that the term can be applied “not just to the soldiers on the front line” but also to “the communities those soldiers belonged to and the families who had to live through four years of ever more desperate warfare.”27 In 1916 the Lancet published “War Shock in the Civilian,” acknowledging that “[w]hile the stress of war on the soldiers is discussed, it should not be forgotten that the nervous strain to which the civilian is exposed may require consideration and appropriate treatment.”28 Perhaps this should not be surprising, for as Lesley D. Clement notes in “From ‘Uncanny Beauty’ to ‘Uncanny Disease,’” shell shock was often identified as a form of hysteria and “a manifestation of childishness and femininity.”29 In contrast to the view published in the Lancet, many trench poets emphasized the vast chasm between men’s and women’s physical and mental experiences of the war. Soldier-poet Edmund Blunden wrote of that divide as an “impassable gulf,” Edgell Rickword as “two incommunicable worlds,” and Richard Aldington as “gesticulating across an abyss.”30 As James Campbell writes in “Combat Gnosticism: The Ideology of First World War Poetry Criticism,” women’s perspectives on the war were largely silenced due to the “construction of combat experience as a wholly separate realm of gnosis.”31

Montgomery’s “Our Women,” like many other non-canonical poems of the First World War, exposes the mental trauma commonly experienced by women during war.32 As Sharon Ouditt writes in Fighting Forces, Writing Women, “revealing one’s unhappiness [was] unpatriotic.”33 Rarely was the war’s impact on women publicly acknowledged or examined; instead, their sacrifices and sufferings were minimized, and they were asked to adopt a public mask of stoic detachment or even cheerful optimism. Home-front support for the war was managed through social and cultural messages regarding the appropriate expression of grief. Carol Acton in Grief in Wartime explains that governments manufacture consent to war through “subscribing meaning to wartime death that limits or silences grief and replaces it with abstractions of honour and pride.”34 Suzanne Evans’s research shows that in Canada, as elsewhere, women were asked to mask and constrain their mourning. Evans cites the article “When Bowed Head Is Proudly Held,” which appeared in the Toronto Globe in 1916, reporting the fear that women’s mourning dress might discourage enlistment; in response, the National Council of Women was requesting that women who had lost men in the war should not wear black but rather “a band of royal purple on the arm to signify that the soldier they mourn died gloriously for his King and country.”35 Managing what can be worn is easier than controlling what can be felt. Women’s private war writings reveal the conflicting emotions that the bereaved experienced, while, as Acton observes, “public mourning, on the other hand, left little room for ambivalence: stoic acceptance and pride was the public face of grief”—a demand that often resulted in “enormous stress on the bereaved.”36 Montgomery’s “Our Women” calls attention to the gap between what is felt and what can be expressed.

“The Cheerful Lie”

In the first stanza of “Our Women,” a new bride determinedly represses her grief at the death of her husband. She encourages herself to believe the implausible story that was often written in letters informing women of their husband’s, son’s, and sweetheart’s deaths: The end was quick and painless; he “died with a smile.” Mirroring the action of her husband at the moment of his death, the young bride smiles “for his sake,” offering up the arduous task of concealing her own anguish as an act of patriotic service akin to that of her husband’s. Like soldiers who neither speak nor write of the horrors they witness at the front, women are also engaged in the nationwide practice of telling, selling, and believing what Montgomery refers to in both Rilla and her journals as “the cheerful lie.”37 Rilla’s response to her brother’s death echoes the same script as Montgomery’s war poem. After receiving a letter from her brother’s commanding officer informing the family that Walter “had been killed instantly by a bullet during a charge,” Rilla says to herself, “I will keep faith, Walter. … I will work—and teach—and learn—and laugh, yes, I will even laugh through all my years because of you and because of what you gave.” Despite Rilla’s resolve, the novel provides details that expose the immense strain in pretending to be cheerful: Smiles are described as if they are the uniforms of the home front, “a little stiff and starched” or “starched and ironed.” A cheerful facade is put on like a garment, as when Rilla’s mother and sister watch Jem depart for military duty, and the narrator writes, “Mother and Nan were smiling still, but as if they had just forgotten to take the smile off.”38

The same strain is evident upon a close reading of “Our Women.” The young bride may smile for the sake of her dead husband, but her “eye is bright” with unshed tears, and her cheeks are flushed with the effort of disguising her grief. In her examination of women’s poetry of the First World War, Nosheen Khan observes that women commonly concealed their war grief and anxiety, and that this often resulted in backlash against what was perceived as “the seemingly callous behavior of women, their apparent indifference to the plight of the fighting men.” Khan criticizes those who lacked the imagination to “perceive the traumas” suffered by many women, citing the example of Arnold Bennett, who declared in his 1915 account, Over There: War Scenes on the Western Front, “bereavement, which counts chief among the well-known advantageous moral disciplines of war, is, of course, good for a woman’s soul.”39

Unbearable Isolation

Each of the bereaved women portrayed in “Our Women” is isolated, walled off within her own stanza, set apart from both the grief and the comfort of others. Each speaks to herself in a private monologue of mourning. In the first stanza, the bride attempts to convince herself that she must appear happy; in the second, the mother persuades herself to feel proud that her son is dead. The only woman who allows herself to weep is the woman who has no one to give to the war: This can be read as an ironic reversal, but her tears also underscore her lonely alienation from others.

As well as being estranged from their own emotions during the war, women were also frequently judged for their failure to show grief, placing them in an impossible double bind and illustrating Plain’s observation that “[t]he single most characteristic feature of … women's experience of war was isolation.”40 This overwhelming isolation is also depicted in Rilla through Rilla’s activities and their reception after she has said her farewells and watched her brother Walter leave for the war. Rilla goes about her day as if nothing has happened, and in the evening, she attends a Junior Red Cross meeting, where she is “severely business like,” prompting another woman to comment, “Walter had left for the front only this morning. But some people really have no depth of feeling. I often wish I could take things as lightly as Rilla Blythe.” The concealment of grief is both expected and condemned. Their efforts to maintain the continual pretence of cheer leave many women close to the breaking point, as revealed by Gertrude Oliver’s outburst:

I wish Canada had never sent a man—I wish we’d tied our boys to our apron strings and not let one of them go. Oh—I shall be ashamed of myself in half an hour—but at this very minute I mean every word of it. … Susan, tell me—don’t you ever—didn’t you ever—take spells of feeling that you must scream—or swear—or smash something—just because your torture reaches a point where it becomes unbearable?41

In both poem and novel, Montgomery vividly describes women who struggle with their own doubleness as they attempt to conceal their experiences of trauma behind masks of stoic endurance.

Rilla also exposes the widely held view that women who are unable to control their grief transgress the boundaries of ladylike behaviour and are suspected of being mad. Describing Gertrude’s response to news of her beau’s death, Rilla writes in her diary, “At first she was crushed. Then after just a day she pulled herself together and went back to her school. She did not cry—I never saw her shed a tear—but oh, her face and eyes!” Gertrude’s public stoicism cannot be sustained, however, for in an emotional confrontation with Cousin Sophia, Rilla records that Gertrude gives a “dreadful little laugh, just as one might laugh in the face of death.” When Cousin Sophia reproves Gertrude, remarking, “You ain’t as bad off as some,” Gertrude bitterly replies, “It’s true I haven’t lost a husband—I have only lost the man who would have been my husband. I have lost no son—only the sons and daughters who might have been born to me—who will never be born to me now.” Shocked, Cousin Sophia admonishes Gertrude, saying, “It isn’t ladylike to talk like that,” at which “Gertrude laughed right out, so wildly that Cousin Sophia was really frightened …. [and] asked Mother if the blow hadn’t affected Miss Oliver’s mind.”42 Whether feigning cheerfulness or pride, the characters depicted in Rilla and “Our Women” suggest that distancing oneself from deeply held emotions may estrange women from themselves and others.

Frequently in her own private journal during the war, Montgomery describes the burden of concealing her private self. Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston have noted the complexity of Montgomery’s journal composition. In their introduction to Volume 2 of the Selected Journals, they discuss how as Montgomery “became an increasingly public person, she needed more than ever a secret release for her thoughts” and outline the “new checks on her self-expression” that she felt after marrying Ewan Macdonald and moving to Leaskdale. They write that “the mere fact of her womanhood” was a “check on her self-expression” and describe how she would “put off writing down something that was hard for her to handle emotionally. She seemed to feel threatened by the idea that to write it down was to make it real. On the other hand, she acknowledged that the only way to move beyond a difficult experience was to put it into words, giving it a fixed temporal reality, so that she could proceed with her life.”43 In 1916, Montgomery’s journal describes her exhaustion at being pressured to “wear a mask and assume a cheerfulness I am far from feeling.” Detailing a night spent organizing a pie social in aid of the Red Cross, she wonders “if it were any use to keep up the struggle”: “I have seldom been more sick at heart … But nobody knew it. … I smiled and laughed and jested and engineered the programme; I gave a comic reading that brought down the house; I ate a third of a pie with the purchaser thereof—an awkward schoolboy … We ate that pie in silence and I felt as if every mouthful must choke me.” By the end of 1916, after over two years of war and enforced false cheer, Montgomery reflects on how close she is to mental collapse:

I passed a horrible afternoon and evening. And I could not even show my suffering. I had to repress every sign of it and go to a Missionary meeting. … I sat there while the women talked local gossip before the meeting began, as if they had never heard of the war, and I made no sign. … I read a lengthy screed from the Mission Study Book and knew not one word I was reading; and I walked home afterwards with some of the village women … and smiled and bowed and went through the motions. And inside of me my soul writhed and gibbered on its rack!44

The terms Montgomery uses to describe her mental state can be compared to descriptions of traumatized soldiers who have lost control of their bodies and minds. As both Montefiore and Dowson observe in their analyses of women’s war writing, it was not uncommon for women writers to identify with “absent suffering men … or the dead in Flanders”45 or to use “men’s frames of reference” as they “projected themselves into the male arena.”46 This identification was problematic for women, however, as men’s sacrifices and sufferings were typically acknowledged as being much greater. Montgomery gives voice to women’s experience of wartime trauma in her journal, in Rilla, and in the first two stanzas of “Our Women,” using representational language that draws attention to similarities in men’s and women’s experience of war trauma, a comparison that could not be easily nor directly expressed in public.

When read in the context of Rilla and Montgomery’s journals, “Our Women” exposes the immense gap between women’s private and public selves. Research on emotional regulation, such as that undertaken by Oliver P. John and James J. Gross, has found those who chronically suppress negative emotions are likely to undergo an increase in those emotions, as well as experiencing a decrease in social support and an increased risk for depressive symptoms. Additionally, John and Gross conclude that those who hide emotions such as grief often suffer from a strong sense of inauthenticity, as well as “lower levels of satisfaction and well-being, … less life satisfaction, lower self-esteem, and a less optimistic attitude about the future, consistent with their avoidance and lack of close social relationships and support.”47 In “Our Women,” Montgomery’s hallmark ambiguity, or, as Gammel writes, Montgomery’s “hallmark equivocation,” is manifest in silences and smiles, both what they conceal and how they may be misinterpreted. In a journal entry from January 1920 Montgomery writes, “If we feel very keenly we have to wrap our feelings from sight. To betray them, blood-red and raw, would be indecent. The world despises you if you show it your feelings—and hates you if you don’t!”48 Like many women during the war, Montgomery appears to have believed in the cultural norms that constrained the expression of grief and struggled to conform, while simultaneously rebelling against those very strictures.

Patriotic Motherhood

Joy Demousi argues that the pressure on women to forgo public mourning was especially true for mothers: “In many cultures, mothers were expected to disavow their grief and channel it into forms of patriotism and heightened nationalistic pride.”49 The second stanza of “Our Women” depicts a mother whose only son has been killed in war. He “gave himself with a gallant pride” but now “[s]leeps in a chilly bed.” Coping with deferred grief, the woman imagines her son as if he is only sleeping. As Evans points out, women are often asked during times of national crisis to be complicit in their sons’ deaths, “for if the mother, of all people, can support the giving of her child’s life to a cause, then not only must that cause be of ultimate worth, but it would be shameful for anyone else to give less.”50 Shame is frequently entangled with grief, patriotism, and war.

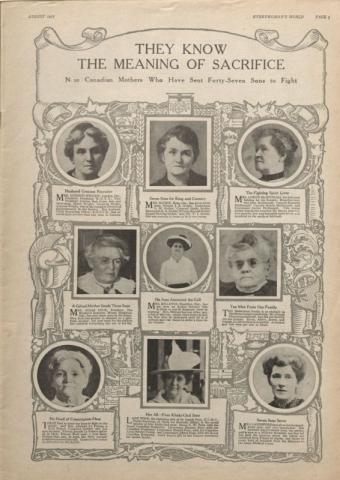

Nearly all countries involved in the First World War attempted to harness the political power of the ideals of Mother and Motherhood. Before the 1918 German offensive, Canadian General Sir Arthur Currie addressed his troops: “To those who will fall I say, ‘you will not die, but step into immortality. Your mothers will not lament your fate, but will be proud to have borne such sons.’”51 Taking pride in a child’s death was one of the ways that mothers were encouraged to find a sense of worth and purpose during the war. Evans cites a December 1915 Everywoman’s World article titled “I Am a Proud Mother This Christmas and I Will Tell You the Reason Why” that offers the account of Mrs. E.A. Hughes as a model for other women’s patriotic war support. Upon receiving a telegram notifying her of her son’s death in battle, Mrs. Hughes’s initial reaction is one of shock, but she shares her emotional journey as an inspiration to other women, telling them how after the shock had passed, “I was terribly, yet gladly sure that the messenger had not made a mistake. … I am a proud mother this Christmas. For I gave Canada and the Empire a Christmas present.” She continues, “I gave them my chiefest possession. I yielded what was more than aught else in the world to me. I sacrificed the life of my boy.”52 Many women, including Montgomery, were likely to internalize such messages and then struggle to meet the emotional demands such sacrifice required.

Like the mother of “Our Women,” Anne Blythe in Rilla of Ingleside also understands the sacrifice that her country asks of her and explains it to her daughter with “white lips and stricken eyes,” as she quotes from Kate Tucker Goode’s 1914 poem “Caleb’s Daughter”: “When our women fail in courage, / Shall our men be fearless still?”53 Rilla is made to understand that her country’s call upon “our women” is that they enlist in the battle to conquer their own emotions: Women’s stoic endurance will give the nation and its men the support needed to wage and win the war.

Guilt and Shame

In “Our Women,” both the grieving bride and mother define themselves in their relationships to the soldiers they have loved and lost; both women model their behaviour after that of their soldier, giving smile for smile, pride for pride. The only woman who openly expresses grief is the woman without a loved one to sacrifice to the war. She sits alone and weeps in shame. This inversion of the natural expression of feeling highlights the ways in which the war has overturned nearly all normalcy in women’s lives. Examining the war journals of British author May Sinclair, another woman writer who had no loved one to give to the war, Suzanne Raitt writes,

despite the government’s efforts to recast the roles of mother, wife, and indeed of “woman” in the mould of war, women seem to have remained confused and uneasy, afraid of doing things wrong, but unsure how to do things right. … femininity is repeatedly experienced and represented as shame at times of social and cultural crisis. … All patriarchies do this, but patriarchies at war do it most of all.54

In Montgomery’s war writings, women frequently compare their sacrifice with that of men at the front only to reach the conclusion that their own trauma is negligible—and that to feel otherwise is shameful. The mother depicted in the second stanza of in “Our Women” uses this comparative language (“Shall I be less proud?”) and believes that the only reasonable response available to her is to dismiss her own feelings and echo her son’s gallant pride. This comparison of men’s and women’s trauma—despite its subsequent dismissal—suggests a second, more complex reading of the poem that problematizes that dismissal and publicly recognizes women’s sufferings in wartime.

Many women on the home front, not only mothers, felt a deep sense of guilt that they were not on the front lines. Rilla wishes that she were a boy “speeding in khaki by Carl’s side to the western front,” not out of a longing for romantic adventure but because “[t]here were moments when waiting at home, in safety and comfort, seemed an unendurable thing.” Women on the home front deny themselves the right to protest anything in their lives, for as Susan says, “Rheumatism is bad enough but I realize, and none better, that it is not to be compared to being gassed by the Huns.”55 The same guilt depicted in “Our Women” and Rilla is also described in Montgomery’s journals. Her entry for 6 January 1915 records, “When I snuggle down in my comfortable bed I feel ashamed of being comfortable. It seems as if I should be miserable, too, when so many others are.”56 She gives almost these exact words to Gertrude in Rilla: “How everything comes back to this war. … We can’t get away from it—not even when we talk of the weather. I never go out these dark cold nights myself without thinking of the men in the trenches. … When I snuggle down in my comfortable bed I am ashamed of being comfortable. It seems as if it were wicked of me to be so when many are not.”57

Like many women during the war, Montgomery and the women she writes about struggle with guilt and shame as they adopt a pretence of equanimity. What women are asked to endure, however, lasts far longer than the war. As Rilla grimly says, “‘I cannot bear it,’ … And then came the awful thought that perhaps she could bear it and that there might be years of this hideous suffering before her.”58 In her journals, Rilla, and “Our Women,” Montgomery makes it clear that the women who answer their country’s call, unlike the men who have enlisted to fight, are never discharged from their service or its continuing grief.

Entangled Tragedies

Montgomery’s personal situation was closest to the solitary figure described in the third stanza of “Our Women”: She was without a man to give to the war. Montgomery’s husband, Ewan Macdonald, was forty-four years old when the war began; her eldest son, Chester, had just turned two; and her second son, Hugh, was stillborn on 13 August 1914, just nine days after England declared war on Germany.59 The loss of her infant son devastated Montgomery. Research on the effects of stillbirth deliveries has found that, after losing a child at birth, “[m]any women perceived themselves as failures at the role of mother, wife, daughter and daughter-in-law.”60 Shame and self-blame are common responses to miscarriage and stillbirth,61 and many parents experience what researchers term disenfranchised grief: “[P]ersonal feelings of extreme grief [are juxtaposed] with society’s dismissal of such a short-lived or even ‘unborn’ life.”62 In 1914, Montgomery’s first journal entry after Hugh’s death records her anguish:

On August 13th a darling little son was born to me—dead. Oh God, it almost killed me. At first I thought I could not live! All the agony and pain I have endured in my whole life heaped together could not equal what I felt when I realized that my baby was dead—my bonny sweet boy, so beautiful and perfect. … I can never forget the horror of the night that followed. They had taken my baby away and laid him in a little white casket in the parlor. I was alone. I could not sleep. I could not cry. I thought my heart would burst.

In the same entry, she records that her convalescence “was a dreary time. … And while I was lying helpless bad war news began to come, too—news of the British defeat at Mons and the resulting long dreary retreat of the Allies. … Everything seems dark and hopeless.”63

In her thinking and writing, Montgomery’s maternal grief becomes entangled with the dead of the war. Like the women whose sons died far from home, she is haunted by the thought of her son “lying lonely in his little grave” and imagines hearing his cry: “Little Hugh was calling to me from his grave—‘Mother, won’t you come to me?’” In late November 1914 she writes, “all this fall I have been racked with worry over the war and tortured with grief over the loss of my baby.” The war and Hugh’s death are twinned sources of grief in another journal entry that Montgomery, again pregnant, writes in August 1915:

It is just a year to-day since little Hugh was born dead. Oh, that hideous day! Shall I ever be able to forget its agony? And will it be repeated in October? This thought is ever present with me. I have had some back attacks of nervous depression lately—one last night that was almost unbearable. My condition—the war news—the weather—all combined to make me very miserable.64

For Montgomery, the tragedy of her son’s death at birth is linked to the larger national tragedy of the war, and, given this context, the shamed, weeping woman of “Our Women” who has no son to surrender to the state is a poignantly disguised expression of the author’s own grief. Montgomery never sent a son of her own to war, but biographer Rubio writes, “Maud suffered over the loss of local boys as much as Ewan did: she had taught many of them in Sunday School or directed them in church programs, and every loss was personal. And each time she and Ewan had to comfort families over their loss of a son, she relived her own intense grief at the death of her second baby.”65

In Rilla, Anne Blythe also explicitly connects her memories of Joyce, her first child, a stillborn daughter who died (as described in Anne’s House of Dreams),66 with her living sons’ participation in the First World War. When Jem, the eldest son, tells his parents that he wishes to enlist, “both thought of that other time—the day years ago in the House of Dreams when little Joyce had died.” After her son Walter has been killed in action, when Anne’s youngest son, Shirley, asks permission to join the flying corps, Anne makes another connection with the stillborn child lost years previously: “Anne did not say anything more just then. … She was thinking of little Joyce’s grave in the old burying-ground over-harbour—little Joyce who would have been a woman now, had she lived—of the white cross in France and the splendid grey eyes of the little boy who had been taught his first lessons of duty and loyalty at her knee.”67 Unlike the fictional Anne, Montgomery had no sons to give to the war. Her journals acknowledge the shame and ambivalent relief she felt: “I thank God that Chester is not old enough to go—and as I thank Him I shrink back in shame, the words dying on my lips. For is it not the same thing as thanking Him that some other woman’s son must go in my son’s place?”68 The doubleness and difficulty that lie beneath the surface of “Our Women” reveal Montgomery’s struggles to resolve her conflicting emotions. This is a poem that attempts what Baetz calls the “complex management of competing ideas and identities, resolved [by force of desire] into coherence,”69 and, although the poem’s top note rings with patriotic support for the war, its undertones play a dirge of shame and loss.

Montgomery dedicated her fifth Anne novel, Rainbow Valley (1919), to three of the local Leaskdale men killed in the war. However, as she indicates in an essay “How I Became a Writer,” she wrote Rilla of Ingleside not for the Canadian boys who went off to fight but for the young women of Canada, to depict “their bravery, patience and self-sacrifice.”70 As she was reviewing the proofs for the novel, Montgomery received a letter from her publisher “complaining that Ingleside was ‘too gloomy,’” and requesting that she “omit and tone down some of the shadows.”71 She refused. The shadows that her publisher remarked upon in Rilla are also cast in “Our Women.”

Closets Full of Skeletons

Although “Our Women” has been dismissed as a naively patriotic verse, when read in the context of Montgomery’s other war writings, it reveals itself to be a complex poem that supports the war effort while simultaneously exposing the severe emotional traumas of the war that many women endured. Anne’s son Walter laments, “It must be a horrible thing to be a mother in this war—the mothers and sisters and wives and sweethearts have the hardest times.”72 In early twentieth-century Canada, women were primarily defined by their familial status in relation to men (mother, sister, wife, sweetheart, unmarried, childless). Montgomery supported and outwardly adhered to this cultural norm, yet she also protests against it: “Our Women” exposes the ways in which women’s connections to men frequently prevent women from expressing their full emotions. Women are asked to shoulder the heavy and unending burden of emotional dishonesty.

I have argued in a previous essay that women’s war poetry is often displaced from the front lines of battle and depicts an interior or psychological war: Anger is sublimated, and grief must be controlled and negotiated.73 In her essay “Reframing Women’s War Poetry,” Claire Buck establishes that women’s war poetry frequently attempts that negotiation: “By far the majority of women poets during both wars [the First and Second World Wars] wrote elegies for dead soldiers.”74 Strikingly and at its core, Montgomery’s “Our Women” subverts the traditional elegy. There is no mourning for soldiers who have died; tears are shed only for the absence of bodies to lie on the altar of sacrifice. Mourning is reserved for the woman who sits apart, shamed and isolated in her own No Man’s Land. This woman feeds herself upon the sorrow of failure, a failure to participate in the womanly patriotism that her culture and her country demand of her. “Our Women” is an anti-elegy that focuses not on men’s deaths, but on women’s interior experiences of war. The poem speaks with an undercurrent of quiet despair as it catalogues women’s limited options for action and emotion during the First World War.

Several years after the Armistice, Montgomery describes in her journal an encounter with a neighbour who attempts to compliment her, saying, “Mrs. Macdonald, you have done a great deal for our little church. … And you always seem so bright and happy that it heartens us up to see you.” Montgomery bitterly reflects, “Happy! With my heart wrung as it is! With a constant ache of loneliness in my being. … Well, I must be a good actress. I wonder how many other women I know, who seem ‘bright and happy,’ have likewise a closet full of skeletons. Plenty of them, I daresay.”75 The demand that women appear “bright and happy” was central to prosecuting the First World War and extended long after its finish. Bridget Keown writes of the arduous emotional demands that women faced during the First World War “and indeed, every war that came before or after it”: “[W]omen’s grief must be contained, behind asylum walls, within homes, and in public discourse and media, all of which demand their continued silence and complicity. … Recognizing the enormity of their grief forces us to reckon with their humanity, as well as the inhumane way in which their grief was treated.”76 Montgomery’s war writings expose the mental trauma that she and many of “Our Women” experienced during the Great War as a consequence of their struggles against the demands to mask and disguise their personal tragedies.

About the Author: Constance M. Ruzich is the editor of International Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology of Lost Voices (Bloomsbury, 2020). While at the University of Exeter as a 2014–2015 Fulbright Scholar, she researched the use of poetry in British centenary commemorations of the First World War. Her blog Behind Their Lines shares research on lesser known poets and poetry of the First World War, and her essay “Language and Identity: Introduction” is published in Multilingual Environments in the Great War (Bloomsbury, 2021). She is a professor of English at Robert Morris University, Pennsylvania, USA. You can find Connie on Twitter.

- 1 As McIntosh and Devereux discuss in The Canadian Encyclopedia, a Canadian Broadcasting Corporation reader poll in 2014 named Anne Shirley as “Canada’s most iconic fictional character.”

- 2 Manion, “The Two Faces of ‘Anne’” J9.

- 3 Fisher, “‘Watchman’” 103.

- 4 I am indebted to Lesley D. Clement’s research and support, Andrea McKenzie and Jane Ledwell’s edited collection, L.M. Montgomery and War, and Susan Fisher’s essay on Montgomery’s war poetry in that collection. Their work was inspirational, and this essay hopes to extend that research.

- 5 Montgomery, The Watchman.

- 6 Qtd. in Lefebvre’s “The Watchman and Other Poems” 173, 175, 178.

- 7 Fisher 95.

- 8 Montgomery, My Dear Mr. M 3.

- 9 Fisher 98.

- 10 Excepting its appearance in more recent editions of Montgomery’s work, “Our Women” was subsequently published only in Eliza Ritchie’s Songs of the Maritimes: An Anthology of the Poetry of the Maritime Provinces (McClelland and Stewart, 1931) and John Robert Colombo and Michael Richardson’s We Stand on Guard: Poems and Songs of Canadians in Battle (Doubleday, 1985).

- 11 Garvin, Canadian Poems 4.

- 12 McKenzie and Ledwell, Introduction 15.

- 13 Fisher 103.

- 14 Armstrong 324.

- 15 Gammel, Looking for Anne 246.

- 16 Vincent, “Canadian Poetry” 167, 170.

- 17 Baetz, Battle Lines 10.

- 18 Montefiore, “‘Shining Pins’” 54, 55, 57.

- 19 Dowson 35, 40.

- 20 For further discussion of Montgomery’s war novel, see also Mary Beth Cavert’s “‘To the Memory of’: Leaskdale and Loss in the Great War,” in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley D. Clement, MQUP, 2015, pp. 36–53; Kazuko Sakuma’s “The White Feather: Gender and War in L.M. Montgomery’s Rilla of Ingleside,” in L.M. Montgomery and Gender, edited by E. Holly Pike and Laura M. Robinson, MQUP, 2021, pp. 19–43; and Lesley D. Clement’s “From ‘Uncanny Beauty’."

- 21 Schweik, “Writing War Poetry” 540.

- 22 Ruzich, International Poetry 175, 186, 210.

- 23 Plain, “‘Great Expectations’” 52.

- 24 Montgomery, RI 148; emphasis in original.

- 25 Swanwick, Women and War 1.

- 26 Robinson, “L.M. Montgomery’s Great War” 118.

- 27 Grogan, Shell Shocked Britain 3–4.

- 28 “War Shock in the Civilian,” Lancet vol. 1, 4 Mar. 1916, qtd. in Tate, “HD’s War Neurotics” 242.

- 29 Clement cites Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914–19: The Medical Services (1925) by “(Sir) Andrew Macphail, who became renowned for his literary, military, and medical contributions.” Clement, “From ‘Uncanny Beauty’” 57.

- 30 Qtd. in Tylee, The Great War 54.

- 31 Campbell, “Combat Gnosticism” 214.

- 32 While beyond the scope of this essay, it should be noted that combat soldiers suffered from what is has come to be known as primary trauma (or PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder), while women on the home front were likely to suffer from what is now known as secondary trauma (or complicated grief). The difference between these experiences of psychological trauma and the ways in which they are represented in the poetry of the First World War is an area for further study.

- 33 Ouditt, Fighting Forces 95.

- 34 Acton, Grief in Wartime 3, 5. McKenzie’s “Women at War,” 332, 334, 342, offers further discussion of Acton’s ideas in the context of Rilla of Ingleside.

- 35 Evans, Mothers of Heroes 93; Evans cites “When Bowed Head Is Proudly Held,” Toronto Globe, 8 May 1916.

- 36 Acton 37–38.

- 37 Montgomery, RI 160 and CJ 3 (24 July 1915): 200.

- 38 Montgomery, RI 238, 239 (emphasis in original), 55, 156, 70.

- 39 Khan, Women’s Poetry 174, 151.

- 40 Plain 41.

- 41 Montgomery, RI 158, 179–80; emphasis in original.

- 42 Montgomery, RI 208, 209.

- 43 Rubio and Waterston, Introduction xi, xiii, xix.

- 44 Montgomery, CJ 3 (9 Feb. 1916): 212; (28 Feb. 1916): 215; (10 Dec. 1916): 259.

- 45 Montefiore 62.

- 46 Dowson 50, 51.

- 47 John and Gross, “Healthy and Unhealthy” 1319–20.

- 48 Montgomery, CJ 2 (31 Jan. 1920): 239; emphasis in original.

- 49 Demousi, “Gender and Mourning” 213.

- 50 Evans 7–8.

- 51 Arthur Currie, qtd. in Evans 77.

- 52 Mrs. E.A. Hughes, qtd. in Evans 86.

- 53 Montgomery, RI 50, 144. This allusion was identified by Mary Beth Cavert, “If Our Women Fail in Courage, Will Our Men Be Fearless Still?” Shining Scroll, vol. 1, 2014, p. 4.

- 54 Raitt, “Contagious Ecstasy” 65–66.

- 55 Montgomery, RI 179, 128.

- 56 Montgomery, CJ 3 (6 Jan. 1915): 179.

- 57 Montgomery, RI 117–18; emphasis in original.

- 58 Montgomery, RI 234, 143.

- 59 For further discussion of Montgomery, motherhood, and the death of Hugh, see Rita Bode’s “L.M. Montgomery and the Anguish of Mother Loss,” in Storm and Dissonance: L.M. Montgomery and Conflict, edited by Jean Mitchell, Cambridge Scholars, 2008, pp. 50–66, and Tara K. Parmiter’s “Like a Childless Mother: L.M. Montgomery and the Anguish of a Mother’s Loss,” in L.M. Montgomery and Gender, edited by E. Holly Pike and Laura M. Robinson, MQUP, 2021, pp. 316–30.

- 60 Burden et al., “From Grief.”

- 61 Barr, “Guilt- and Shame-Proneness” 494.

- 62 Lang, “Perinatal Loss” 184.

- 63 Montgomery, CJ 3 (30 Aug. 1914): 162–63.

- 64 Montgomery, CJ 3 (3 Sept. 1914): 165 and (8 Sept. 1914): 167; (20 Nov. 1914): 172; (13 Aug. 1915): 203.

- 65 Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery 192.

- 66 Joyce’s death occurs in chapter 19 of Montgomery’s Anne’s House of Dreams, “Dawn and Dusk.”

- 67 Montgomery, RI 52, 256.

- 68 Montgomery, CJ 3 (1 Jan. 1915): 178.

- 69 Baetz 10.

- 70 Montgomery, “How I Became a Writer” 3.

- 71 Montgomery, CJ 4 (5 Mar. 1921): 309.

- 72 Montgomery, RI 154.

- 73 Ruzich, “Distanced, Disembodied, Detached” 105, 116.

- 74 Buck, “Reframing Women’s War Poetry” 34.

- 75 Montgomery, CJ 4 (18 Aug. 1921): 334.

- 76 Keown, “‘Shock from Loss.’”

Works Cited

Acton, Carol. Grief in Wartime: Private Pain, Public Discourse. Palgrave, 2007.

Armstrong, Isobel. Victorian Poetry: Poetry, Poetics and Politics. Routledge, 1993.

Baetz, Joel. Battle Lines: Poetry in English and the First World War. Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2018.

Barr, Peter. “Guilt- and Shame-Proneness and the Grief of Perinatal Bereavement.” Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, vol. 77, 2004, pp. 493–510.

Buck, Claire. “Reframing Women’s War Poetry.” Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century British and Irish Women’s Poetry, edited by Jane Dowson, Cambridge UP, 2011, pp. 24–41.

Burden, Christy, et al. “From Grief, Guilt Pain and Stigma to Hope and Pride—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Mixed-Method Research of the Psychosocial Impact of Stillbirth.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, vol. 16, no. 9, 2016. Project Muse, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-016-0800-8.

Campbell, James. “Combat Gnosticism: The Ideology of First World War Poetry Criticism.” New Literary History, vol. 30, no. 1, 1999, pp. 203–15.

Clement, Lesley D. “From ‘Uncanny Beauty’ to “Uncanny Disease’: Destabilizing Gender through the Deaths of Ruby Gillis and Walter Blythe and the Life of Anne Shirley. L.M. Montgomery and Gender, edited by E. Holly Pike and Laura M. Robinson, MQUP, 2021, pp. 44–67.

Demousi, Joy. “Gender and Mourning.” Gender and the Great War, edited by Susan R. Grayzel and Tammy M. Proctor, Oxford UP, 2017, pp. 211–29.

Dowson, Jane. Women, Modernism and British Poetry, 1910–1939. Ashgate, 2002.

Evans, Suzanne. Mothers of Heroes, Mothers of Martyrs: World War I and the Politics of Grief. McGill-Queens UP, 2007.

Fisher, Susan. “‘Watchman, What of the Night?’: L.M. Montgomery’s Poems of War.” McKenzie and Ledwell, pp. 94–109.

Gammel, Irene. Looking for Anne of Green Gables. St. Martin’s, 2008.

Garvin, John W. Canadian Poems of the Great War. McClelland and Stewart, 1918.

Grogan, Suzie. Shell Shocked Britain: The First World War’s Legacy for Britain’s Mental Health. Pen and Sword, 2014.

John, Oliver P., and James J. Gross. “Healthy and Unhealthy Emotion Regulation: Personality Processes, Individual Differences, and Life Span Development.” Journal of Personality, vol. 72, no. 6, Dec. 2004, pp. 1301–34.

Keown, Bridget. “‘Shock from Loss’: The Reality of Grief in the First World War.” Nursing Clio, 27 Mar. 2018, nursingclio.org/2018/03/27/shock-from-loss-the-reality-of-grief-in-the-first-world-war/#:~:text=During%20the%20First%20World%20War,their%20sons%20and%20husbands%20overseas.

Khan, Nosheen. Women’s Poetry of the First World War. UP of Kentucky, 1988.

Lang, Ariella, et al. “Perinatal Loss and Parental Grief: The Challenge of Ambiguity and Disenfranchised Grief.” Omega, vol. 63, no. 2, 2011, pp. 183–96.

Lefebvre, Benjamin. “The Watchman and Other Poems, 1916.” The L.M. Montgomery Reader, Volume Three: A Legacy in Review, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 2015, pp. 172–79.

Manion, Eileen. “The Two Faces of ‘Anne.’” The Montreal Gazette, 13 Feb. 1988, p. J9.

McIntosh, Andrew, and Cecily Devereux. “Lucy Maud Montgomery.” The Canadian Encyclopedia, www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/montgomery-lucy-maud, 30 Jan. 2020.

McKenzie, Andrea. “Women at War: L.M. Montgomery, The Great War, and Canadian Cultural Memory.” The L.M. Montgomery Reader: Volume Two, A Critical Heritage, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, pp. 325–49.

McKenzie, Andrea, and Jane Ledwell. Introduction. McKenzie and Ledwell, pp. 3–37.

McKenzie, Andrea, and Jane Ledwell, editors. L.M. Montgomery and War. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2017.

Montefiore, Janet. “‘Shining Pins and Wailing Shells’: Women Poets and the Great War.” Women and World War I: The Written Response, edited by Dorothy Goldman, Macmillan, 1993, pp. 51–72.

Montgomery, L.M. Anne’s House of Dreams. Seal, 1981.

---. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889–1911. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 2012–2013. 2 vols.

---. “How I Became a Writer.” Manitoba Free Press, 3 Dec. 1921, Christmas Book Section, p. 3.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals, The Ontario Years, 1911–1917, edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills P, 2016.

---. My Dear Mr. M: Letters to G.B. MacMillan, edited by Francis W.P. Bolger and Elizabeth Epperly. McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1980.

---. The Poetry of Lucy Maud Montgomery, edited by John Ferns and Kevin McCabe. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1987.

---. Rilla of Ingleside. Virago, 2014.

---. The Watchman and Other Poems. McClelland, Stewart and Goodchild, 1916.

Ouditt, Sharon. Fighting Forces, Writing Women: Identity and Ideology in the First World War. Routledge, 1994.

Plain, Gill. “‘Great Expectations’: Rehabilitating the Recalcitrant War Poets.” Feminist Review, vol. 51, no. 1, 1995, pp. 41–65.

Raitt, Suzanne. “‘Contagious Ecstasy’: May Sinclair’s War Journals.” Raitt and Tate, pp. 65–84.

Raitt, Suzanne, and Trudi Tate, editors. Women’s Fiction and the Great War. Clarendon P, 1997.

Robinson, Laura M. “L.M. Montgomery’s Great War: The Home as Battleground in Rilla of Ingleside.” McKenzie and Ledwell, pp. 113–27.

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Doubleday, 2008.

Rubio, Mary, and Elizabeth Waterston. Introduction. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume 2: 1910–1921, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1887, pp. ix-xix.

Ruzich, Constance M. “Distanced, Disembodied, and Detached: Women’s Poetry of the First World War.” An International Rediscovery of World War One: Distant Fronts, edited by Robert B. McCormick, Araceli Hernández-Laroche, and Catherine G. Canino, Routledge, 2021, pp. 104–21.

Ruzich, Constance M., editor. International Poetry of the First World War: An Anthology of Lost Voices. Bloomsbury, 2021.

Schweik, Susan. “Writing War Poetry Like a Woman.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 13, no. 3, 1987, pp. 532–56.

Swanwick, H.M. Women and War. Union of Democratic Control, 1915.

Tate, Trudi. “HD’s War Neurotics.” Raitt and Tate, pp. 241–62.

Tylee, Claire M. The Great War and Women’s Consciousness. U of Iowa P, 1990.

Vincent, Thomas B. “Canadian Poetry of the Great War and the Effect of the Search for Nationhood.” Intimate Enemies: English and German Literary Reactions to the Great War 1914–1918, edited by Franz Karl Stanzel and Martin Löschnigg, Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1993, pp. 165–75.

Article Info

Copyright: Constance M. Ruzich, 2023. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.

Copyright: Constance M. Ruzich, 2023. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.