This paper provides an overview of L.M. Montgomery’s literary friendship with her Scottish pen friend, George Boyd MacMillan, and considers how their compatibility was grounded in the writers they read and loved, a bond which was acknowledged with a dedication to MacMillan in Emily of New Moon. This paper will explore an epistolary conversation they launched from verses they exchanged and identify favoured books that MacMillan sent to her as gifts.

… nothing gives me such a sense of life still being worth while as to receive a letter from one of the “kindred spirits” of the leisurely old days. For a moment or two I find myself back there in the unhurried years and emerge from my brief communion with the past refreshed as if I had drunk a rejuvenating draught from some magic spring.

—L.M. Montgomery, Letter to MacMillan, 26 August 1924

L.M. Montgomery was a prolific letter writer and letter reader. Her most extensive (existing) letters were sent to her friend in Scotland, George Boyd MacMillan. He received over 180 letters, notes, and postcards from her between 1903 and 1941. Nearly every one contained the name of a book or author, a poem, or an essay for comment or discussion. MacMillan and Montgomery were also skilled at choosing gift books for each other, which they exchanged every year. MacMillan was in tune with Montgomery’s emotional sensitivities and earned himself a place in her affection and admiration for his attentiveness. As proof of their closeness, she dedicated Emily of New Moon to him, the first of her books to be dedicated to a personal male friend.

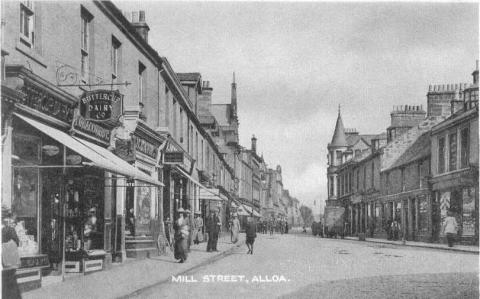

George MacMillan lived in Alloa, Scotland, located between Edinburgh and Stirling, where the River Forth meets the Firth of Forth. His place of residence was important when he was first brought to Montgomery’s attention as a prospective pen pal because she loved (the idea of) Scotland. She established her own Scottish lineage and heritage in her earliest letters as a link to him, a distant kinsman. In her first letter she identified her family clans: “Our family of Montgomery claim kinship with the Earls of Eglinton. My mother was a Macneill, which is even ‘Scotchier’ still.”1

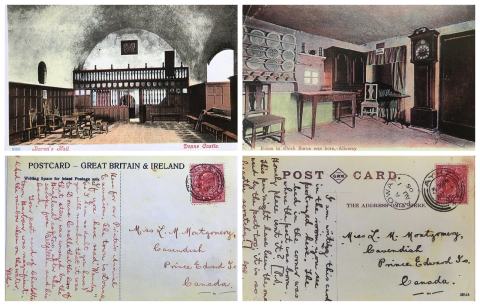

Right: Postcard from George B. MacMillan to L.M. Montgomery. “Room in which Burns was Born, Alloway,” 1 Aug 1905. L.M. Montgomery Institute, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE. Photo by donor Joanne Sealy Craig, 2000.

MacMillan responded to her declaration of kinship by sending her postcards during his holidays from literary landmarks such as Doune Castle from Scott’s Waverly2 and the birthplace of Robert Burns: “Really, the word ‘Ayr’ at the top of your last letter gave me a thrill!”3 Montgomery responded. Scotland was a literary homeland for Montgomery, more so than an actual ancestral one, because she had always been immersed in Scottish literature through books and The Royal Reader, the school textbook series used when she was a student.4 Therefore, and most importantly, MacMillan shared her literary heritage. “Lately I re-read ‘Rob Roy.’ I suppose you’ve read it. I understand it is an insult to a Scotchman to ask him if he has read Scott’s novels!”5 As Dr. Jenny Litster pointed out at the 2012 L.M. Montgomery Institute conference on Cultural Memory, Montgomery’s personal heritage might have been described as more Walter-Scottish than Scottish.6 Montgomery’s book dedication to MacMillan in 1923 not only spotlighted her appreciation for his friendship but his personal geography as well—it is her only dedication7 which names a person and a specific location: “To Mr. George Boyd Macmillan / Alloa, Scotland / In Recognition of a Long and Stimulating Friendship.”8 “I hope you will like the dedication,” she wrote.9

A Friend Across the Sea

Emily of New Moon signalled a new direction for Montgomery. She took a clean break from the family of grown-up Anne Shirley Blythe and embraced a new character who mirrored her own emotional and creative terrain and her artistic life. New Moon was an appropriate book to pair with MacMillan; it was not by chance that she chose him for the honour of a dedication.10 While Montgomery was writing Emily in August 1921 to February 1922, she was also recopying her old journals and reliving her past experiences.11 By the spring of 192112 she would have been reading the journal entries chronicling spring and summer of 1911, ten years earlier, when she had planned and travelled on her honeymoon to Britain. On 11 May 1921, she wrote: “She has been ‘Emily’ for the past ten years during which time I have been carrying her in my mind …”13 Trinna Frever noted that the author “had an active relationship with the past” in “Recollection and Remembrance” at the 2012 L.M. Montgomery and Cultural Memory conference—Montgomery’s storytelling was a physical act of remembering.14

Montgomery’s memory linked Emily to her experiences in Scotland, which included walks and conversations with MacMillan and seeing the locations of her favourite Scottish stories. Emily was clearly a product of Scottish heritage, even more explicitly expressed in New Moon’s sequel, Emily Climbs, “‘You will be having Highlandmen for your forefathers?’ [Mrs. McIntyre] said, in an unexpectedly rich, powerful voice, full of the delightful Highland accent. ‘Yes,’ said Emily.’”15 Montgomery’s fictional landscapes in Emily retain a patina from the literary Old World the author read about and imagined, a flavour of the cultural, oral traditions of her family and community,16 and, finally, the real world she toured on her honeymoon and relived while she was writing Emily of New Moon.

“I am glad you liked Emily,” she wrote to MacMillan in 1924.17 One of the elements MacMillan would have noticed in Emily was the presence of the girl’s imagined beings. Although young Emily’s companions in New Moon were fairies, green folk, elves, and a wind woman, it was far from being a fairy story,18 but it evolved during a time of otherworld interest after the Great War. Montgomery was on the verge of constructing Emily’s story during a heyday of fairy news in Britain centred on two young girls in Yorkshire, England, who produced photographs of “Cottingley Fairies” in 1917.19 While Montgomery enjoyed the idea and ambience of a fairy-inhabited land, she did not count herself among the true believers of fairies in the post-war times. Still, the stories were good reading, and clippings from both of the readers were sent back and forth. Montgomery said, “I used to believe wholeheartedly in fairies when I was a child and there was nothing made one so resentful as having that belief inexorably wrested from me by maturity. I’d love to believe in them yet if I could …”20

The Cottingley fairy sensation was at its peak with the publication of popular author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Coming of the Fairies in 1922, a book that Montgomery recommended to MacMillan five years later after she read another fairy article:

What in the world do you make of the enclosed clipping on fairies? Conan Doyle wrote a book about it a few years ago and reproduced all the photographs. I saw it—and if the photos are, as alleged, absolutely genuine I am staggered. It is unbelievable, of course. But what explanation is there if fraud be barred out? ... In regard to the photos the only explanation I can give—a very lame one I admit—is that thought waves can be photographed and that these children imagined the fairies so strongly that their thoughts made an impression on the sensitive plate. Well, I should like to believe in fairies!!21

Montgomery was an experienced photographer, and she clearly was flummoxed by the apparent authenticity of these photographs.

Her fascination with the fairy phenomenon in Britain was ongoing and, as late as December 1936, Montgomery was still reacting to stories she received from MacMillan. One such example was a letter published in John O’London Weekly, 16 May 1936, about a fairy sighting in Wales. Throughout 1936 readers of the Weekly sent letters to the publication and shared their own experiences seeing fairies.22

But those letters about fairies!! What did you make of them? I cut them all out and put them together in an envelope. One can’t believe all those people were lying. And could they all simply have imagined them. The whole subject of fairies has always intrigued me. How came it about that they were believed in, in a hundred different forms, for thousands of years, in every country and among [every] race of men? Somebody shall have seen something at sometime … Can children see things older people cannot? Or do their inward fancies embody their nerves in a visual way and does this faculty pass as they mature? Either of these explanations might help to solve the problem of fairies. But I frankly admit those letters are beyond me. Those people were not children.23

However, in her fiction Montgomery did not need to explain the “problem of fairies.” Emily was free to inhabit the topography of the author’s imagination and, like her creator, look through the thin fabric that separated the worlds of workaday lives and imagination-enriched lives. Montgomery could expect that George MacMillan, a fellow writer who had also climbed an “Alpine Path”24 in his career (albeit a Scottish one), would appreciate Emily as the story of a writer’s journey—and perhaps noting that Emily of New Moon’s late father, Douglas Starr, was also “a poor young journalist, with nothing in the world but his pen and his ambition.”25 By dedicating Emily of New Moon to MacMillan, Montgomery acknowledged her bond with him, not only because he was a Scot, but because he shared a background of hard work and an appreciation for the mysteries and enjoyments in life—and he was a lifelong “scribbler”26 and reader, just like her.

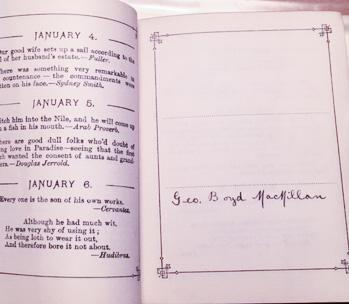

George was the youngest of seven children in the McMillan (he changed the spelling of his name from McMillan to MacMillan) family, born on 6 January 1881 in Alloa, Clackmannanshire, Scotland, six years after Lucy Maud Montgomery. His father, John, operated the second-generation family grocery store for about forty years on Mill Street in Alloa between the shops of the shoemaker and dressmaker. John died when George was about eight years old.27

After John McMillan’s death, the family moved from Mill Street, a commercial area in the middle of town, to Castle Street, an industrial area, near the river. One sister worked in the woollen mills and yarn factory; the brothers in the port and harbour.28 George lived with female family members for most of his life on Castle Street. His mother died in 1902 just before he started writing letters to Canada.29

MacMillan was an aspiring writer; at age fourteen he started a job as an apprentice and printing-machine operator for the local Alloa Advertiser, where he taught himself shorthand.30 For over forty years he was a reporter for the Alloa Journal and wrote songs, topical verses and humorous poetry, parodies, and a regular column called “Man in the Street.” He loved astronomy and hiked in the nearby Ochil Hills with his friend and colleague, John Gardner, revelling in the aurora borealis and paraselene.31 A lifelong friend, Rev. Dr. George Jeffrey, Moderator of the Church of Scotland, described him as one of the town’s best-known personalities, a most loved, highly respected townsperson who had “a sunny outlook on life.”32

Another friend of MacMillan from Alloa was Roy Carmichael,33 who corresponded with a group he called “the American writer's club,”34 established by Miriam Zieber, a novice writer based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.35 Carmichael was likely the agent who brought George into Zieber’s circle. Zieber, acting as an epistolary matchmaker, wrote to MacMillan on 20 July 1903 to recommend another member of her writers' support group, L.M. Montgomery:

There is a darling wish very close to my heart for many a day: that of forming an exclusive circle of writers for entirely unselfish help towards each member. So far I am sure of the quality of character for this purpose of only you, Mr. [Ephraim] Weber, a young lady of superior ability living on Prince Edward Island, and myself … I’ll broach the matter to Miss Montgomery and if she consents I’ll give you an introduction to her and you’ll find her a most delightful correspondent.36

When MacMillan entered her life, Montgomery had just turned twenty-nine, and he was about to have his twenty-third birthday. She was tethered to the farm with her grandmother for what looked like a road with no bend, and the lives of each correspondent seemed similar. They had both lost a parent when they were young, which affected their economic circumstances and domestic responsibilities later as caretakers and, consequently, had suffered a loss of the freedom to relocate. However, the writers were able to cross the ocean through the written word and pictures they exchanged; they could envision each other’s landscapes and initiate conversations sparked by the contents of their mail.

At first, Montgomery was faithful to Zieber’s directive to assist each other in their profession; Montgomery, the more experienced writer, sent advice on where to send work and how much was being paid. Their correspondence soon found a more personal comfort level, which matured and deepened over the years. They began as collegial writers but continued as congenial readers.

MacMillan seemed well suited to the Canadian author. At home his humour was “in full play in conversations which delight[ed] his friends, rich as it was in literary allusion and well stored in local lore.”37 MacMillan was unpretentious; he gained her trust. He was fun and interesting, and, especially in the last decade of her life, his correspondence was a safe harbour, one of the few calming and comfortable spaces in her increasingly difficult personal life. She welcomed the freedom and therapeutic value of writing to a broad-minded and sympathetic correspondent: “In my letters to them [MacMillan and Weber] I ‘let myself go,’—writing freely from my soul, with no fear of being misunderstood or condemned … If I could not ‘write out’ freely certain words, opinions and fancies they would remain bottled up in my soul …” 38 MacMillan may have been just as pleased to have a bright female friend. They were proper friends; her letters were always addressed to Mr. MacMillan and signed L.M. Montgomery/Macdonald.

Montgomery’s letters were far-ranging, but structured,39 and she wanted them to be worthwhile. Her letters were long because she could not write as frequently as she wanted. She could always write quick, short letters to family and friends but wanted to take her time when she wrote to him.40 Most of the letters had a similar outline: her news and reflections of the day, season or year(s), usually copied from her notebook. These portions were recorded in her journals and repeated in some letters to another pen pal, Ephraim Weber. As a second feature, the letters included titles of books, essays, poems, or articles she had read or written (with critiques and recommendations), and requests for MacMillan’s reaction. There were nearly 300 entries for books, authors, and literary quotations mentioned in the complete correspondence.41 And, in their earliest letters, they explored topics that were unique to their relationship, written without a self-consciousness or knowledge that these words might ever be made public.

Affinity and Allusions

Montgomery wanted their conversation to be open and candid: “You may ask me any question you wish on any subject and I will answer as freely and frankly as there may be light in me to do.”42 MacMillan wrote in this spirit from the very beginning. Even though his letters have not survived, Montgomery helpfully repeated the questions he asked, the first being posed in 1904 regarding their unhappiness with their current situations. He wondered if she thought that suffering helped them develop intellectually and spiritually, and she answered, “Discontent impels us to measure our happiness by what we can put into our environment, not by what we can get out.”43 This sentiment is similar to Mrs. Allan’s words to Anne Shirley in Anne of Avonlea, that “[our lives] are broad or narrow according to what we put into them, not what we get out.”44 Five letters from Cavendish to Alloa crossed the ocean in 1905, and in these first messages she continued to use a friendly, warm tone, “Good-night to you and pleasant dreams, friend over the sea,”45 and she even extended an invitation for a walk, “I’m going back to the woods now to get some ferns. Want to come?”46 In addition, she told the courtship story of her great-grandmothers, Betsy and Nancy,47 and her own “courtship” story (poetry reading and book discussions) at age twelve with her first sweetheart, Nate Lockhart.48 If MacMillan saw her as a potential love interest, her mention of a literary sweetheart and a tale of a great-grandmother’s courtship by a persistent and clever suitor could have encouraged him to explore her feelings about romance.

By 1906 their discussions of intellectual growth and literature, and their likes and dislikes, established a mutual compatibility, and throughout the next year they probed conceptions of happiness, duty, and love using selections of poetry and prose. MacMillan was the first to broach the topic of love sometime in mid-1906, by sending a poem, “Lost Love,” about Argive (of Argos) Helen by Scottish poet Andrew Lang.49 Montgomery did not address the poem in her next letter and replied, instead, with a clipping of Margaret Preston’s poem about Moses, “Unanswered Prayer,”50 which lamented what would have been lost if Moses had been left to tend his sheep instead of answering a call of duty. “I wonder, though, if Moses might not have been happier in the ‘forty years of desert watching with his sheep’ … I do not think that doing one’s duty always brings happiness.”51

Unknown to MacMillan, Maud was happy.52 She had been courting, or been courted by, the local minister, Rev. Ewan Macdonald, who had been installed in the Cavendish church shortly before she began her correspondence with MacMillan in 1903. MacMillan would have assumed she was an unattached woman, since Miriam Zieber invited mostly unmarried writers into her literary circle. However, his perception may have been altered when she wrote that she had been having arguments, “long arguments,” with a male friend about whether duty or happiness was the purpose of existence. In that same happiness/duty letter she revealed that her successful and well-liked minister was going to Scotland, and said, “we are all very sorry he is going away.”53 If MacMillan was adept at reading between the lines, he might have considered that the male friend who argued for duty and the well-liked minister were one and the same.

Before she wrote her next letter, Montgomery became engaged to the minister, Rev. Macdonald, on 12 October 1906, and he left Prince Edward Island soon afterward, arriving about 28 October to study in Glasgow, Scotland, about seventy kilometres (forty miles) away from MacMillan. She urged both men to meet each other, which they did and possibly very soon after Ewan’s arrival, because by late November 1906 she was answering several of MacMillan’s questions about affinity and attraction. The sudden appearance of MacMillan’s interest in her thoughts about attraction coincided with Macdonald’s arrival in Scotland. From November 1906 until June 1908, when Anne of Green Gables was published, the two pen pals hashed out their perceptions of love.

This long exchange about relationships can be characterized as an impersonal example of the quality and candidness of their platonic friendship, but within context it can also be read as the response of an undeclared suitor suddenly confronted with a rival, and a mismatched one at that. In a letter written soon after Macdonald’s arrival in Scotland, MacMillan introduced the topic of recognizing an “ideal affinity.” Montgomery attempted to answer and conclude that inquiry with a poem,

In regard to what you say about wondering if you have met [your ideal] and not recognized her I wish I could quote a very beautiful sonnet along that very idea but I do not remember it except in fragments. It begins,

“Two shall be born the whole wide world apart,

Speak different languages, think different thoughts,

and yet be guided by destiny over lands and seas, through many dangers,

read life’s meanings in each other’s eyes.

And two shall walk some narrow way of life

so near that if they but stepped a step aside they would meet,

but never do and go unsatisfied to the end.”54

She goes on to say, “Love is a subject we haven’t referred to much in our letters yet but I see no reason why we should not discuss it frankly, like any other psychological problem.” Her responses to his earnest questions about the “psychological problem” took on a slightly lofty tone when she explained that she was writing from past experience, while he was likely writing hypothetically: “Of course, if you have never loved your part of such discussion could be only theory. I frankly admit that I have so that at least my opinions would be stamped with the reality of my own experiences.” She ended this same letter with a confession, which could have been directed at MacMillan or offered as an explanation about her secret fiancé, “Again, men with whom I am in perfect intellectual accord have never attracted me in the slightest degree. That is the problem I’ve been butting up against all my life.”55

Her next letter in spring of 1907 began with a brief mention and dismissal of “Lost Love.”56 She answered his questions on friendship versus love, success of marriage between unlike partners, her experience with infatuation (citing Herman Leard and Edwin Simpson),57 and qualities of attraction. After four years and seventeen letters Montgomery more or less told her friend that they could only be friends, even if they seemed perfectly matched. She concluded her argument with a quotation by Tennyson and another confession, “‘We needs must love the highest when we see it.’ I don’t believe it now. It is not true … Oh, [love] is a horribly perplexing subject and I grow dizzy thinking of it.”58 George MacMillan surely knew the feeling after reading her letters. However, they both continued to press on.

Five months later she devoted half of a letter to the topic of love and repeated, “Speaking broadly I think that between woman and woman or man and man likeness attracts; between man and woman unlikeness.” He asked if the pain of unrequited love was worth it. She said yes and related it to her own experience (although he might have been asking for himself): “My answer is emphatically ‘yes.’ To be sure, my love was not ‘unrequited.’ But … it was for a man [Herman Leard] who was my inferior and whom I could not for a moment think of marrying …” Montgomery turned to Olive Schreiner’s The Story of an African Farm to embellish her position and emphasize that having loved and lost was worth the pain: “There is another love that blots out wisdom, that is sweet with the sweetness of life and bitter with the bitterness of death, lasting for an hour; but it is worth having lived a whole life for that hour.” As for ideal love, she continued, there was no such thing, “… ideal love … could only be found in an ideal world in ideal people. Emerson says ‘There is a crack in everything God has made.’” In summary, this letter in September 1907 confirmed what her friend may have suspected about her and the minister: “If two people have a mutual affection for each other, don’t bore each other, and are reasonably well mated in point of age and social position, I think their prospects of happiness together would be excellent.”59

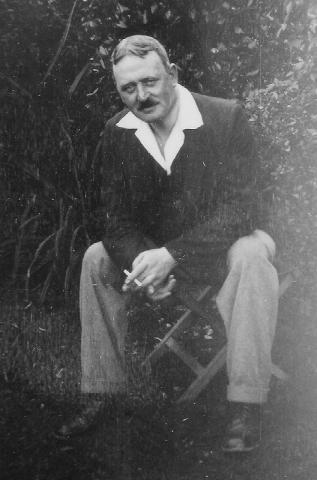

Right: Photo of L.M. Montgomery, 1903. Digital image courtesy of Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph. L.M. Montgomery Collection, XZ1 MS A097051. Please contact University of Guelph Library (libaspc@uoguelph.ca) regarding any planned print or electronic republication of this image.

MacMillan had been waving his epistolary flag of recognition (“Lost Love”), hoping she would acknowledge him, but she would not (“Fate”). Montgomery reaffirmed her belief that there is no ideal love that has both friendship and passion (Schreiner), but even if it is imperfect (Emerson) it is worthwhile. She admitted she would settle, or had settled, for a practical marriage. She finally located her copy of the complete poem, Fate, with its definitive final stanza, and sent it as the last word:

And yet, with wistful eyes that never meet,

With groping hands that never clasp, and lips

Calling in vain to ears that never hear,

They seek each other all their weary days

And die unsatisfied—and this is Fate!60

Their choices to create a safe, circumspect distance with literary selections and avoid direct declarations spared each of them embarrassment and misunderstanding. The result was a kind of platonic intimacy—thus setting the terms of their relationship and an enduring friendship. Whether a subtext existed or not, this manner and volume of personal revelation did not happen again. The book was finally closed on any possible long-distance romance by 1908 when she became a busy, successful book author, and in May 1911 when she revealed her upcoming marriage and plans to visit him in Scotland.

After seven-and-a-half years, MacMillan and Montgomery finally met in person, for the only time, on her honeymoon. (He and Ewan met for the second time.) The two correspondents’ high expectations for each other were rewarded.61 She was delighted with him and enjoyed his company as much in person as she did on the written page.62 They were together for only about ten days. In Alloa, George entertained the couple on their walks: “He knows all the legends and traditions of the surrounding country and is a most congenial conversationalist.”63 At MacMillan’s recommendation,64 they made a literary tour together in Berwick and Spittal, near the heart of Walter Scott’s poem, Marmion, and its sites at Flodden Field and Lindisfarne. It was far too short a time to share with her friend, but Montgomery held on to those memories with great affection over the years.65

Fragrant Minutes

MacMillan remained a long-term correspondent because he wrote engaging letters that were in sync with Montgomery’s intellect, sense of humour, and interests (gardens, cats, astronomy, and natural and mysterious phenomena).66 He represented her beloved literary Scottish landscape, and he understood her language of poetry. Perhaps the most distinctive foundation of their friendship is represented by the reading material he chose for her. For Montgomery the leisure reading MacMillan provided was a refuge; she found relief in the act of reading the books she received from her Scottish friend.

Montgomery’s reading history (and abundant use of allusions) is being analyzed in the work of Dr. Emily Woster, who has catalogued and cross-indexed an immense (ongoing) database of titles and allusions in Montgomery’s papers and texts.67 Dr. Jennifer Litster has explored the influence of British authors in Montgomery’s writing (from books mostly supplied by George MacMillan).68 Less recognized is the author’s affection for “domestic” or so-called sentimental poetry and fiction (a genre within which she was sometimes placed),69 which focused on home and family life.

Montgomery provided the Scotsman with a great deal of information about her reading habits, starting with her first letter—she liked to read essays70—and then in her second: “What are your tastes along the line of reading. I revel in history and fiction. Don’t care a great deal for biography—like scientific works … I got hold of a splendid children’s story the other day 'At the Back of the North Wind' by George McDonald ... I love [Kipling’s] Jungle stories—they are grown-up fairy tales.”71

It was clear that Montgomery did some heavy lifting in her reading, consuming volumes like Grote’s histories72 and Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,73 a reading experience that sometimes left her feeling “swallow[ed] up … As I march with his stately procession of forgotten heroes and forgotten fools I get the uncomfortable feeling that I am as insignificant as a grain of dust …”74 After two years of correspondence about reading tastes, in 1905 MacMillan sent his first Christmas gift book, The Four Gardens,75 and learned that he had struck the perfect chord.76 “I don’t know when I’ve read anything that pleased me as that book did. It is simply idyllic and I’ve already read it over four times. It has caught the very spirit of a garden and seemed to lead me into an enchanted world … Many many thanks for your gift and the thoughtfulness expressed in it,” Montgomery wrote.77 He also discovered that, besides the other well-known titles he sent (poetry by Browning and Byron, bestsellers by Graham and Hodgson Burnett) there were lesser-known works (lesser-known to Montgomery) that could appeal to her attraction to nostalgia, beauty, and comfort.

The book exchange continued almost every year until about 1940 with nearly perfect receptions.78 “I think you come the nearest to anybody I know to ‘inspiration’ in choosing your Xmas gifts with regard to the recipient’s taste. If you had ransacked a continent you couldn’t have found anything that would have given me more pleasure than ‘The Heart of A Garden.’”79 In current vernacular, she was saying, “You get me.” Garden books pleased her, and other titles earned him praise too, “I was delighted about the Princess Mary’s gift book. With your usual felicity you hit upon the very thing I had been wanting.”80 The Gift Book81 was a collection of stories and fables with high-quality, colour art by writers such as James Barrie, Rudyard Kipling, and Kate Douglas Wiggin. Montgomery also enjoyed The Friendly Road, in which a farmer leaves his home and engages in unfettered roaming. “My sober friend, have you ever tried to do anything that the world at large considers not quite sensible, not quite sane? Try it! It is easier to commit a thundering crime.”82 The friendly nostalgic road trip was a “dear thing” for Montgomery.83

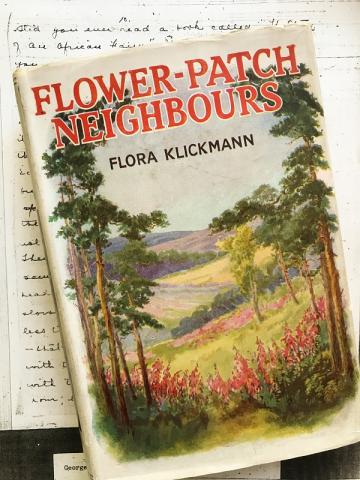

However, what earned MacMillan much of Montgomery’s lasting and repeated gratitude were gift books by a trio of widely read British “domestic” writers—Flora Klickmann, Wilhelmina Stitch, and Fay Inchfawn. Although they were immensely popular in their time, these authors did lack the stature of her favourite classics, and very few of their books were saved in the remains of Montgomery’s personal library. In 1982 about 180 of her personally owned books were placed in the Archival and Special Collections at the University of Guelph. Only two of MacMillan’s gift books were left in the collection, a wedding gift of Poems of Robert Browning, and The First Hundred Thousand by Ian Hay.84 None of the rest of MacMillan’s gifts was included in the books acquired from Stuart Macdonald, Montgomery’s son. Other books had already disappeared after her death in 1942 (probably sold by her son, Chester Cameron Macdonald). Of the books Montgomery sent to Scotland as gifts, the books she authored were kept together and purchased by Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph, but other gift books were omitted from the collection. That neither Montgomery’s gift books to Scotland nor MacMillan’s gift books to Canada were kept with their personal libraries85 rendered authors like Klickmann less conspicuous in inventories of Montgomery’s literary consumption.

Flora Klickmann was the successful British editor of Girl’s Own Paper—her articles in it evolved into bestselling books, The Flower Patch series. Klickmann was a perfect match for the Canadian author, a writer on her own wavelength with similar interests and expression. When MacMillan sent them to her, Klickmann’s books were new to Montgomery, yet familiar, with their focus on a cottage-garden environment and idyllic landscape. Jennifer Litster summed up the British author’s appeal at the 2018 L.M. Montgomery and Reading conference:

The Flower Patch books … are not novels but not non-fiction either; rather they are autobiography on the slant, a kind of life writing. [The characters are] narrator, Klickmann herself, with [husband] Ebenezer, “the Head of Affairs,” mostly absent in London where he works on the war effort; two best friends, Virginia and Ursula, and various maids of work and local residents (who are mostly there to add comic relief). The books combine short sketches of incidents, gardening tips and lore, reflections and religious philosophy, and some verbal jousting between friends. Some episodes are set in London, but most chapters are set in the Forest of Dean where, although war time concerns such as rationing and household economy are part of the narrative, the appeal largely lies in the escapism.86

Although the Flower Patch author did not enter MacMillan’s literary orbit until 1922, Klickmann had already earned high praise as an editor and writer for many years. By 1914 her reputation was solidified as “the prima donna in the Art of Domestic Accomplishments.”87 The positive reception of her work was similar to the appeal of Montgomery’s books, something that MacMillan would have noticed, especially in bookstore ads in British papers. The Westminster Gazette, London, published a short and effective recommendation in an advertisement on 17 May 1916: “You just smile your way right through it, Flower-Patch Hills by Flora Klickmann.”88 The Scotsman (Edinburgh) printed similar sentiments on 13 December 1917: “In some books the setting is more than the story, and this is the case with Miss Flora Klickmann’s captivating volume, Between the Larch-Woods and the Weir.”89

Flora Klickmann’s Flower Patch series won top positions on Montgomery’s bookshelves. “I shall put it in my special bookcase where my dearest books are,”90 she wrote. “I can’t tell you how I love them [the Flower Patch books] and how much pleasure they have given me. I keep them altogether in a little green-painted bookstand in my room and many a sleepless night of anxiety and worry in the past four years I have been comforted and helped by them.”91 She wrote repeatedly about her love for MacMillan's gift books. Several letters underscore the restorative power of reading for Montgomery, especially during the tremendously stressful time for her after 1931 when crises within her family and personal illness drained her emotional resources. “During several weeks of the past year when I was ill and worried and blue I re-read all those ‘Flower Patch’ books you have sent me. They soothed and rested and cheered me. I cannot tell how much. Surely that is the proper function of literature in a world like this!”92 She wrote, “I read them over and over and never tire of them. Each one seems like a visit home.”93

In the late 1920s and 1930s, MacMillan began to send her poetry by another British female writer. Poetry was her first love, and he made more good choices for her, beginning in 1927 with selections by Wilhelmina Stitch. Montgomery did not name a book by the writer in her letters, so he may have sent her clippings from publications—or, it could have been a three-volume collection of “Fragrant Minute” poems (1925, 1926) or Silken Threads (1927).94 Montgomery was familiar with the poet and may have seen an article about her in a Canadian publication, Maclean’s Magazine on 1 September 1925, “The ‘Fragrant Minutes’ of Wilhelmina Stitch.” Stitch was the pen name of Ruth Jacobs Cohen Collie who was born in England and lived in Winnipeg, Manitoba, from 1912 until the death of her husband in 1919. She also wrote under the name Sheila Rand when she lived in Canada. She worked as a copy editor and literary editor for newspapers and returned to Britain in 1923 when she married again. Montgomery would have recognized a kindred spirit in this hard-working writer whose young interests mirrored her own:

There was a circulating library in connection with [her father’s bookstore], and little Ruth Jacobs read constantly. At the age of nineteen she was better versed in English literature than many a graduate who had spent years preparing for his M.A. degree. Hers was not an academic training, but a result of an insatiable appetite for reading.95

In Canada, Collie’s daily verses were called The Finer Things in Life, and in London they were changed to The Fragrant Minute. Through syndication, Stitch became known all over the British Empire: “Within six months she was the most quoted writer in the Daily Sketch, London.”96

Montgomery enjoyed Stitch’s “Whom the Gods Love,”97 and in 1935 she wrote, “Wilhelmina Stitch’s verses ‘The Companionship Road’ seem to ring the bell. So many of her verses do that. I suppose she would not be placed very high by the critics, but I wonder if she had lived in ancient Greece and expressed her views and feelings in classic Greek she might not have rivaled Sappho.”98 Whether Collie garnered critical acclaim or not was probably of little importance to her readership. Like Montgomery’s, her popularity was grounded in her connection to her readers, not critics. After Collie’s death in 1936, Montgomery wrote,

I regretted the death of Wilhelmina Stitch deeply. I shall miss her charming verses. I think of all she wrote the one I loved best was one she wrote about moving from an old house.

The wall shed dusty powdery tears

when they took the mirror it loved for years.99

Perhaps the most crucial virtue that attracted Montgomery to this writer, especially in the 1930s, was Collie’s emphasis on courage “… there is joy, laughter, humor and tenderness to be derived from any kind of daily occupation, if one keeps one’s heart functioning; that most of all the one thing that counts in this world is courage and the ability to keep smiling when one’s heart is weeping.” 100

Another author whom MacMillan introduced to Montgomery was the prolific Fay Inchfawn, often described as the “Laureate of the Home.”101 Inchfawn, was the pen name of Elizabeth Rebecca Daniels Ward. Ward’s books were published in the early 1920s, resulting in an explosion of popularity for her books, The Verse-Book of a Homely Woman (1920), Verse of a House-Mother (published by The Girl’s Own Paper, 1921), Through the Windows of a Little House (1923), and The Adventures of a Homely Woman (1925).

Photo of poem, “Fools,” by Fay Inchfawn, p. 400. Private collection of Mary Beth Cavert, 2020.

Ward’s poetry and stories appeared in Girl’s Own Paper and Woman’s Magazine, edited from 1908 to 1931 by Flora Klickmann, and were picked up by newspapers throughout Britain before her books were published. In February 1910 one of her short stories received a notable review: “Fay Inchfawn’s short story, ‘Love the Builder,’ should be read by every girl who aspires literary fame.”102 In January 1921 the editor of the Exeter and Plymouth Gazette noted that a reviewer “devote[d] litres of pages to a glowing review of a new book of poems entitled, The Verse Book of a Homely Woman. Fay Inchfawn, the new poetess, looks like she is making her mark.”103 Six months after Verse Book was published, there were already six editions in print.104

By the time MacMillan mailed an Inchfawn book to Canada, the British author was on her way to sales of over 200,000,105 and Montgomery joined her fandom. “I enjoyed Fay Inchfawn’s book tremendously. There is such a flavor about it. I liked her volume of poems too but not so well as her prose. I liked it every whit as well as the Flower Patch series and I liked them exceedingly.”106 Montgomery received at least two of Inchfawn’s books (not named) in the late 1920s and a third in 1930. The second one arrived while she was in Prince Edward Island in July 1927,107 and she read from it and used it as the basis of her talk to a Women’s Institute meeting about Women of the Bible.108 Her delight with Fay Inchfawn was enhanced in the summer of 1928 when she received a fan letter from Mary Ward, Inchfawn’s daughter. Montgomery replied to the fan letter, as she always did, and received a thank-you letter that would have been signed “E.R. Ward”; beneath it was the author’s familiar pen name in brackets. It prompted her to “let out a yelp” in happy surprise.109 The two authors exchanged a few letters, at least, because in 1932 MacMillan asked if she had ever received any books from Inchfawn—the answer was no, “It is only to you I am indebted for them.”110 Fay Inchfawn’s last contribution to Flora Klickmann’s Girl’s Own Paper came in 1930, just before Klickmann’s retirement. (Montgomery’s stories were eventually printed in Girl’s Own also, but not until 1937.)111 MacMillan’s gift books furnished their relationship with a literary intimacy. Fay Inchfawn and her fellow popular British women writers were the kind of reading that Montgomery needed. “Everything [Fay Inchfawn] writes has a charm for me.”112

Maud and Ewan were living in beautiful Norval, Ontario, during most of the period she was adding domestic fiction and poetry to her home library. Her boys were young adults, entering their university years, which brought disorienting challenges for Montgomery as a parent. It was also a time in which she became a grandparent, a life milestone she did not share with correspondents. She did begin, however, to tell MacMillan about Ewan’s illnesses, which started to accelerate in 1934 after eight years of good health. Her last letter from the Norval Manse was written before another traumatic transition for the author and her husband. Ewan was forced to resign on 13 February 1935, and the Macdonalds had to leave their home, with great sadness and haste. Soon after an upbeat letter to Scotland in 1936, she was compelled to confront the unravelling of her own family structure through the behaviour of her oldest son, Chester, and Ewan’s continuing illnesses.113 As Montgomery lost control of her own storyline and her own people, MacMillan supplied fictional companions who controlled their own environment in smaller spheres—in their gardens, in their hospitality, and in common daily tasks.

MacMillan might not have been a reader of Klickmann, Stitch, or Inchfawn himself, but he recognized Montgomery as one of their own. He fed her a steady stream of work by these homey writers between 1922 and 1936; she kept it all near at hand on her special bookshelves and in her notebooks. She reread the books and clippings to enter the environments of enchanted worlds, love, pleasure, comfort, rest, cheer, and home that she found in them. No aspect of her real life offered any solace of this kind in 1936. Nonetheless, she built her own Canadian “Flower Patch” story inhabited by a new homely heroine in Jane of Lantern Hill; she collected material during the summer of 1936 and wrote the book from August 1936 to February 1937. It was published 5 August 1937, and she sent it to MacMillan a few months later: “I wrote the book because I loved it.”114 She loved it because she was at home in it, a haven centred among fields, gardens, friends, and food. As Elizabeth Epperly wrote, “I believe we should look to Jane of Lantern Hill if we want to see, pressed into one place, all the homey things Montgomery herself loved, as she described them over the years in her letters and her journal.”115

Beautiful Friendship

MacMillan’s friendship with L.M. Montgomery was so long-lasting, intuitive, and healthy that it eventually transcended the literary interests on which it was based. Did he suspect that her personal life was not as stable as she wanted it to appear? There is no way to know, of course, but by the 1930s she openly expressed gratitude in almost every communication:

… we were good friends long before we met. And, although our brief sojourn together [on the honeymoon] was very delightful, I think even if it had never occurred, our friendship would have been just what it is, because it is not a friendship founded on personal intercourse at all. Really, I am coming to see what a very wonderful thing our friendship has been … it seems to me something predestined—something that just had to happen. Looking back, I realize now how much would have been lacking in my life had this correspondence had never materialized.116

His letters provided a kind of equilibrium, a badly needed feeling of normalcy.117 “My letters from my friends are about all I have to help me keep up my morale,” she wrote.118 We can imagine his distress when she revealed her devastating decline, especially when she told him not to write until she improved.119 Letters were the only way he could offer comfort from a distance, and he did write and included Scottish heather, which was then in bloom.120 In 1941 she sent him four cards, and near the end of summer in 1941 she began to address him as “Dear Friend” instead of “Mr. MacMillan.” Her last note arrived four months before her death, written on 23 December 1941: “I thank God for our long and beautiful friendship. There are few things in my life I have prized as much as your friendship and letters.”121

A few years after Montgomery’s death, MacMillan’s eyesight became too poor to continue working, and he retired in 1946. He never married and lived in the same house in Alloa for sixty-four years. In his last year, he moved to a care home and died in December 1952 at age seventy-two.122 His correspondence from L.M. Montgomery was placed in the hands of his niece and nephew, Margaretha (Greta) and George McMillan. In 1974 Montgomery’s letters, some postcards, and photographs were purchased by Library and Archives Canada. Greta’s grandsons uncovered additional postcards and items in 2019—they are in the George Boyd MacMillan Family Collection at the L.M. Montgomery Institute, University of Prince Edward Island. The books that Montgomery wrote and sent to MacMillan were purchased from a bookseller in Glasgow, Scotland, in 1989 by the University of Guelph Archival and Special Collections.

L.M. Montgomery’s closest friends were those people who had known her a long time, since before she became famous, and these were the friends to whom she dedicated her books, “I cannot bring myself to put on the title page of my books the name of any person who has not meant something to me in the way of inspiration and friendship.”123 They were friends who made her laugh and think, and who were loyal and supportive. George MacMillan was certainly one of those, and for someone she had met only once in person, he had staying power, and they never ran out of topics to discuss. He grew in importance to her well-being over time and did it through the power of the written and read word.

George would never see Canada, meet heads of state, or be a bestselling author, but he could experience those things vicariously through Montgomery’s letters and sincerely applaud her success. The Canadian would never travel to all the places in Great Britain that George toured, or climb its many ancient towers, or walk among the hills and mountains like he did, but she could enjoy them through the descriptions he wrote for her. Their common ground was nourished by living on islands, their love of stories, the stars, companion cats, woodlands, and pleasing each other. “I enjoy discussing your news and opinions quite as much and indeed more than relating my news and opinions,” she wrote.124 Their friendship was fuelled by reading, and the author found comfort in hard times from the person she held dear through his letters and the books he sent to her in hopes that they would, in the words of his gift inscription in 1924, “lead to The Land of Happy Hours.”125

Acknowledgements: For permissions, assistance, materials, and friendship, an abundance of many decades of gratitude to the Heirs of L.M. Montgomery, Inc., Dr. Francis Bolger and Dr. Elizabeth Epperly, Dr. Jennifer Litster, Carolyn Strom Collins, Dr. Mary Rubio, Dr. Elizabeth Waterston, Dr. Kevin McCabe, and Simon Lloyd. Special appreciation to Duncan and Morag McMillan and Ian McMillan for sharing their family treasures. Thank you to Emily Woster, Kate Scarth, Lesley Clement, Jane Ledwell, and Alyssa Gillespie for patience, guidance, and refinement.

About the Author: Mary Beth Cavert, an independent Montgomery scholar with an M.A. in Educational Administration, was a public-school teacher for thirty-four years. She specializes in the personal, historical, and literary context of Montgomery’s kinship ties. Her research has been included in The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery, and she has been a contributing writer in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, The Intimate Life of L.M. Montgomery, and The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album. She authors and publishes The Shining Scroll and the L.M. Montgomery Literary Society social media accounts and website. She has finished editing the complete correspondence from L.M. Montgomery to George B. MacMillan, L.M. Montgomery’s Letters to Scotland, and is updating a manuscript of Montgomery’s book dedications, L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits. She is a founding member of the board of the Friends of the L.M. Montgomery Institute, a member of the editorial board of the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, and a recipient of the 2020 L.M. Montgomery Institute Legacy Award.

Social Media @LMMontgomeryLS:

Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest

Banner image derived from postcard Now Ready: Kilmeny of the Orchard. 1909. KindredSpaces.ca, 1001.SI.LMMGBM.PC.036b.

- 1 Montgomery, Letters 29 Dec. 1903.

- 2 In the text of this card (about 27 June 1906) he responded to her postcard of about 10 June 1906, “Your postcard of Charlottetown Harbour was magnificent. I liked the rainbow sheen on the water.” Montgomery’s postcard of Charlottetown Harbour can be viewed at KindredSpaces.ca, 1001.SI.LMMGBM.PC.016a.

- 3 Montgomery, Letters 23 Aug. 1905.

- 4 See Waterston, Rapt in Plaid; Litster, Scottish Context 34; Rubio, “Scottish-Presbyterian Agency.”

- 5 Montgomery, Letters 12 Jan. 1905.

- 6 Litster, “Highlander.”

- 7 Cavert, “I Dwell.” Background for friends named in LMM’s dedications.

- 8 Montgomery, ENM.

- 9 Montgomery, Letters 14 Sept. 1922.

- 10 After she dedicated New Moon to MacMillan (1923) she added her other two lifelong pen pals in the following books, dedicating Emily Climbs to Arthur John Lockhart (1925) and The Blue Castle to Ephraim Weber (1926).

- 11 Woster, “Old Years and Old Books” 154–5.

- 12 Montgomery, SJ 2 (23 Feb. 1921): 402. In February 1921 she had copied entries up to the end of 1910.

- 13 Montgomery, Letters 11 May 1921.

- 14 Frever, “Recollection.”

- 15 Montgomery, EC 185.

- 16 Litster, Context 191–2.

- 17 Montgomery, Letters 26 Aug. 26 1924. Underlined in original.

- 18 Litster, “Golden Road” 65. Jennifer Litster explored the connection of the Kenneth Grahame books, which MacMillan sent to Montgomery, and her earlier books. Litster notes, “The fairyland that Montgomery explores in The Story Girl and The Golden Road lends credibility to ancient superstition, is anchored in history, and is synonymous with childhood perception. In all three areas, there is a marked influence on Montgomery of British children’s writers …”

- 19 “Cottingley.”

- 20 Montgomery, Letters 7 Apr. 1904.

- 21 Montgomery, Letters 24 Apr. 1927. Underlined in original. LMM included a clipping of an article, 28 Apr. 1927, from an unidentified Toronto newspaper: “Two Girls Claim to Have Photographed a Fairy. Visitor to Toronto [E.L. Gardner] Sent by Sir A. Conan Doyle to Exhibit a Set of Negatives That Amaze Scientific World.”

- 22 “John O’London.”

- 23 Montgomery, Letters 27 Dec. 1936.

- 24 A phrase representing the work required to be successful. This was the title of her autobiography, “The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career” (Rubio, Gift 81). “Alpine Path” is found many times in the Emily series, for example, ENM 301–2 and EC 39; the Emily Climbs book title is a direct reference to this phrase. MacMillan was a hiker and the actual path he climbed was to Ben Cleuch, the highest of the Ochil Hills range, where he made “midnight climbs … to see the sunrise” (Gillen, Letter 3).

- 25 Montgomery, ENM 15.

- 26 Montgomery, Letters 29 Dec. 1903.

- 27 Census.

- 28 Census.

- 29 Alloa Genealogy.

- 30 Gillen, Letter 6.

- 31 McCabe, 485.

- 32 Gillen, Letter 3.

- 33 Montgomery, Letters 15 Mar. 1905. Carmichael, a work colleague and neighbour, was corresponding with Miriam Zieber as well as with another Montgomery pen pal, Ephraim Weber, in 1902. Census and newspaper records show that Carmichael was married in 1906 and moved to Quebec in 1907. He was the financial editor for the Montreal Daily Herald and published the Verdun Echo (The Fourth Estate).

- 34 Gillen, Wheel 5.

- 35 Gillen, Wheel 51.

- 36 McCabe, 181.

- 37 Gillen, Letter 3.

- 38 Montgomery, SJ 1 (14 Nov. 1904): 113.

- 39 Montgomery, Letters 31 Mar. 1930. “I have always been a systematic devil … Hence I shall open my correspondence notebook, ascertain the date of my last letter to you, open my journal at that date and proceed to tell you any bit of news or philosophy or fun … That done I shall take your unanswered letters with their batches of clippings and make such comments thereupon as may seem good unto me.”

- 40 Montgomery, Letters 14 Sept. 1922.

- 41 Montgomery, L.M. Montgomery’s. This manuscript includes endnotes for her 130 cards, notes, and letters and identifies about 300 literary entries.

- 42 Montgomery, Letters 6 July 1904.

- 43 Montgomery, Letters 9 Nov. 1904.

- 44 Montgomery, AA 171.

- 45 Montgomery, Letters 15 Mar. 1905.

- 46 Montgomery, Letters 23 Aug. 1905.

- 47 Montgomery, Letters 5 June 1905. This story also appears in Montgomery’s 1911 autobiography, The Alpine Path. It was published first as a short story in 1903, “A Pioneer Wooing,” in Farm and Fireside and adapted for The Story Girl (1911) in Chapter VII, “How Betty Sherman Got a Husband.” See Collins, “History” 27–31.

- 48 Montgomery, Letters 3 Dec. 1905.

- 49 Lang, Rhymes 24. The story of Helen of Troy, a beautiful woman taken from her husband resulting in the Trojan War, was the subject of Homer’s Odyssey. Argive Helen is mentioned in The Story Girl, Jane of Lantern Hill, and Anne of Ingleside.

- 50 Preston, “Prayer” 426.

- 51 Montgomery, Letters 29 July 1906.

- 52 Rubio, Gift 119.

- 53 Montgomery, Letters 29 July 1906.

- 54 Montgomery, Letters 29 Nov. 1906.

- 55 Montgomery, Letters 29 Nov. 1906. Underlined in original.

- 56 Montgomery, Letters 1 Apr. 1907. She focused on a verse about aging, underlined in original: “The griefs that leave her gray / The flesh that yet enchains her / Whose grace hath passed away” (Lang, Rhymes 24).

- 57 See Montgomery, SJ 4 (2 Aug. 1931): 145. She used the story of her passionate love for the unsuitable farmer, Herman Leard, and her rejection of the talented and suitable, but prosaic, Edwin Simpson to show that she was attracted to men who were not like her at all.

- 58 Montgomery, Letters 1 Apr. 1907. See Montgomery, SJ 2 (5 Feb. 1911): 46. She quoted Alfred Lord Tennyson. Idylls of the King, 1859, “Guinevere.”

- 59 Montgomery, Letters 11 Sept. 1907. Underlined in original. Montgomery quotes Schreiner, Farm 277. Montgomery includes this Schreiner text in her journal CJ 4 (31 Jan. 1920): 240–1. The book is mentioned in Emily’s Quest, EQ 263. Montgomery quotes Emerson, Compensation 30.

- 60 Spalding, Fate. In 1915 MacMillan asked for another copy of the poem, which she was not able to provide until noted on her postcard in 1928. See “Church Street.”

- 61 Cavert, “Honeymoon” 14–17. She wrote several accounts of the honeymoon trip (none of which contain all the details) in The Alpine Path, her letters to family and friends, her journal record, and her letters to MacMillan while they were travelling.

- 62 They were joined by MacMillan’s fiancée, twenty-one-year-old Jean Allan, who was not mentioned in any letter before the Macdonalds arrived in Scotland. The engagement ended the next year. Montgomery, L.M. Montgomery’s (3 Nov. 1912).

- 63 Montgomery, SJ 2 (13 Aug. 1911): 72.

- 64 Montgomery, Letters 5 June 1911.

- 65 Ewan and George also seemed to be on friendly terms and wrote occasionally. “I saw Mr. McDonald on his return from Scotland and he told me of writing you. Your good opinion seems to have been mutual.” See Montgomery, Letters 8 Jan. 1908. Two postcards from Ewan to MacMillan are in the George Boyd MacMillan Family Collection at the L.M. Montgomery Institute, as well as a photo of Ewan reading on the lawn at Leaskdale that MacMillan received.

- 66 Gillen, Wheel 66–7.

- 67 Woster “Reading.” Woster examines Montgomery’s quotations, reflections, and seasonal reading; she identifies when and under which circumstances the author read or quoted, what texts were cited and with what other texts they were cited, and more.

- 68 Litster, “Golden Road.”

- 69 Rubio, “Subverting” 6–39. Mary Rubio rebuts this classification by focusing on the way Montgomery worked beyond domestic romance to critique society.

- 70 Montgomery, Letters 29 Dec. 1903.

- 71 Montgomery, Letters 7 Apr. 1904.

- 72 Montgomery, SJ 2 (15 Jan. 1921): 396.

- 73 Montgomery, Green Gables Letters 41.

- 74 Montgomery, SJ 2 (5 Dec. 1919): 356.

- 75 The author was Emily Buchanan, “Handasyde.” This book is digitized at babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.c034870088&view=thumb&seq=9. There were four sections: “The Haunted Garden,” “The Old-Fashioned Garden,” “The Poor Man’s Garden,” and “The Rich Man’s Garden.”

- 76 Other garden-related/titled books and the year gifted: The Heart of a Garden (1907), A Book of Gardens (1910), The Secret Garden (1927), The Flower-Patch Among the Hills (1922), Between the Larch Woods and the Weir (1923), The Trail of the Ragged Robin (1924), Flower-Patch Neighbours (1929), Delicate Fuss (1932), and Visitors at the Flower-Patch (1936). The Klickmann books sent between 1922 and 1936 were marketed by RTS-Lutterworth Press as “Books of Cheerfulness” (Montgomery, L.M. Montgomery’s). Montgomery also mentioned two unnamed books by Beverly Nichols, which might have been How Does Your Garden Grow? (published in 1925) and Down the Garden Path (published in 1932).

- 77 Montgomery, Letters 19 Mar. 1906.

- 78 There is no mention of ongoing book exchanges in her letters to Ephraim Weber; although she was known to send books to friends and relatives, this exchange with MacMillan may have been unique.

- 79 Montgomery, Letters 8 Jan. 1908.

- 80 Montgomery, Letters 12 Feb. 1915

- 81 This anthology can be viewed at Gutenberg, gutenberg.org/files/39592/39592-h/39592-h.htm.

- 82 Grayson 4.

- 83 Montgomery, Letters 23 Aug. 1920.

- 84 Woster, Books.

- 85 This is a list of Montgomery’s personal books which have been found in Ontario, the purchaser, and where they are located now: Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. I, Mary Beth Cavert, L.M. Montgomery Institute; This Incredible Adventure, Donna J. Campbell, KindredSpaces.ca, L.M. Montgomery Institute; The Dalehouse Murder, Mary Beth Cavert, private collection; The Trail of the Ragged Robin (by Flora Klickmann), Mary Beth Cavert, private collection; Visitors at the Flower-Patch, a gift to Elizabeth Epperly, Archival and Special Collections, L.M. Montgomery Collection, University of Guelph; Foxe’s Book of Martyrs, Carolyn Strom Collins, Lucy Maud Montgomery Society of Ontario; Flint and Feather, Lucy Maud Montgomery Society of Ontario. In the Osborne Collection, Toronto Public Library—In the Heart of the Ancient Wood, Canadian Poems of the Great War, and When a Man’s Single: A Tale of Literary Life. The Story Girl (inscribed to E. Stuart Macdonald) was found in Saskatchewan, Mary Beth Cavert, private collection.

- 86 Litster, “Ghosts.”

- 87 British Newspaper Archive, Gentlewoman, 28 Feb. 1914 (quoting the Westminster Gazette, London).

- 88 British Newspaper Archive, Westminster Gazette, London, 17 May 1916.

- 89 British Newspaper Archive, The Scotsman, 13 Dec. 1917.

- 90 Montgomery, Letters 18 Feb. 1923.

- 91 Montgomery, Letters 1 Mar. 1936.

- 92 Montgomery, Letters 1 Jan. 1933.

- 93 Montgomery, Letters 28 Jan. 1935.

- 94 “Early Women Writers.”

- 95 Price 77.

- 96 “Winnipeg” [Obituary] 9.

- 97 Montgomery, Letters 15 Mar. 1931.

- 98 Montgomery, Letters 28 Jan. 1935.

- 99 Montgomery, Letters 27 Dec. 1936.

- 100 Price 77.

- 101 British Newspaper Archive, Sheffield Daily Telegraph, Yorkshire, England, 30 Nov. 1922. This title seems to have been conferred shortly after the publication of her first books—”Fay Inchfawn is the acknowledged Laureate of the Home.”

- 102 British Newspaper Archive, Dublin Daily Express, 10 Feb. 1910, Republic of Ireland.

- 103 British Newspaper Archive, Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, 1 Jan. 1921, Devon, England.

- 104 British Newspaper Archive, Lichfield Mercury, 29 July 1921.

- 105 British Newspaper Archive, Wiltshire Times and Trowbridge Advertiser, 17 Dec. 1927.

- 106 Montgomery, Letters 24 Apr. 1927.

- 107 Montgomery, Letters 6 Feb. 1928. “Well, I just took that book along and read several of the poems and gave a rambling talk on the ideas they suggested to me. It ‘took’ tremendously. I think the poem ‘Fools’ despite its title is one of the most beautiful and appealing I have ever read.” See image of Girl’s Own Paper.

- 108 Montgomery, SJ 3 (9 July 1927): 339–40.

- 109 Montgomery, Letters 10 Feb. 1929.

- 110 Montgomery, Letters 11 Dec. 1932.

- 111 “The Girl’s Own Paper Index.”

- 112 Montgomery, Letters 31 Mar. 1930.

- 113 Rubio, Gift 489–94.

- 114 Montgomery, Letters 23 Feb. 1938.

- 115 Epperly, Fragrance 222.

- 116 Montgomery, Letters 11 Dec. 1932.

- 117 Montgomery, Letters 23 Feb. 1938.

- 118 Montgomery, Letters 14 Mar. 1940.

- 119 Montgomery, Letters 23 July 1940.

- 120 Montgomery, Letters 27 Aug. 1940.

- 121 Montgomery, Letters 23 Dec. 1941.

- 122 McCabe, 485; Alloa Genealogy.

- 123 Montgomery, SJ 4 (21 Aug. 1931): 147.

- 124 Montgomery, Letters 27 Dec. 1936. Underlined in original.

- 125 The inscription he wrote in his 1924 gift, The Trail of the Ragged Robin: “To Mrs. L.M. Macdonald, hoping that this ‘trail’ may lead to The Land of Happy Hours. Geo. B. MacMillan.”

Works Cited:

Alloa Genealogy Resources and Parish Registers, Clackmannanshire. Forebears: Names and Genealogy Resources, forebears.io/scotland/clackmannanshire/alloa.

The British Newspaper Archive. Findmypast Newspaper Archive Limited 2020, The British Library. britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk.

Cavert, Mary Beth. “I Dwell Among My People: L.M. Montgomery’s Kindred Spirits.” The Shining Scroll 2016, Periodical of the L.M. Montgomery Literary Society, pp. 15–22. lmmontgomeryliterarysociety.weebly.com/the-shining-scroll-periodical.html.

---. “L.M. Montgomery’s 1911 Honeymoon in Scotland.” The Shining Scroll 2012:2, Periodical of the L.M. Montgomery Literary Society, pp. 14–17. lmmontgomeryliterarysociety.weebly.com/the-shining-scroll-periodical.html.

Census, 1881, 1891, 1901 Scotland; Canada. Ancestry.com. Ancestry.com Operations, 2007.

Collins, Carolyn Strom. “Discovering Fragments of Island History in Montgomery’s Stories.” The Shining Scroll, December 2012:1, Periodical of the L.M. Montgomery Literary Society, pp. 27–31. lmmontgomeryliterarysociety.weebly.com/the-shining-scroll-periodical.html.

“Cottingley Fairies.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, 18 Aug. 2020, Wikimedia Foundation. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cottingley_Fairies.

“Canada’s Early Women Writers.” SFU Library Digital Collections, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada. 1980–2014. digital.lib.sfu.ca/ceww-645/collie-ruth.

“Church Street, Uxbridge, Ont.” George Boyd MacMillan Family Collection, KindredSpaces.ca, L.M. Montgomery Institute, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE. kindredspaces.ca/islandora/object/lmmi:18373#page/2/mode/1up.

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. Compensation. 1841. Houghton Mifflin, 1903, Google Books, google.com/books/edition/Compensation/NjQ3-Ct0Jx4C?hl=en&gbpv=0.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. U of Toronto P, 2014.

The Fourth Estate: A Weekly Newspaper for Publishers, Advertisers, Advertising Agents and Allied Interests. 3 June 1916. Google Books, google.com/books/edition/Fourth_Estate/dg49AQAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=the+fourth+estate,+June+3+1916,+%22roy+carmichael%22&pg=RA23-PA8&printsec=frontcover.

Frever, Trinna. “Recollection and Remembrance: Montgomery’s Structural Retellings and Active Nostalgia.” L.M. Montgomery and Cultural Memory, L.M. Montgomery Institute Biennial International Conference, 21 June 2012, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE.

Gillen, Mollie. Letter to Kevin McCabe. 10 March 1994. K. McCabe L.M. Montgomery Papers. University Archives and Special Collections, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE, Canada. Accession no. 2013-100, box 8.

---. The Wheel of Things: A Biography of L.M. Montgomery, Author of Anne of Green Gables. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1975.

“The Girl’s Own Paper Index” The Lutterworth Press, Cambridge, UK. lutterworth.com/gop/index.php

Grayson, David [Ray Stannard Baker]. The Friendly Road New Adventures in Contentment. London: Melrose, 1913.

“The John O’London Fairy Letters.” Fairyist, The Fairy Investigation Society, 2013/08/. fairyist.com/books-on-fairies/fairy-library.

Lang, Andrew. Ban and Arriere Ban, A Rally of Fugitive Rhymes. Longmans, Green and Co. Gutenberg, 1894. gutenberg.org/files/1855/1855-h/1855-h.htm#page24.

Litster, Jennifer H. “Ghosts and Old Gods: L.M. Montgomery and Flora Klickmann’s Flower Patch Books.” L.M. Montgomery and Reading, L.M. Montgomery Institute Biennial International Conference, 21 June 2018, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE.

---. “Ghosts Going West? The Highlander in the Work of L.M. Montgomery.” L.M. Montgomery and Cultural Memory, L.M. Montgomery Institute Biennial International Conference, 22 June 2012, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE.

---. “‘The Golden Road of Youth:’ L.M. Montgomery and British Children’s Books.” Canadian Children’s Literature/Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 113–14, Spring-Summer 2004, pp. 56–72.

---. The Scottish Context of L.M. Montgomery. 2001. Ph.D. dissertation. Edinburgh Research Archive.

McCabe, Kevin, compiler and editor, and Alexandra Heilbron, editor. The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1999.

Montgomery, L.M. Anne of Avonlea. L.C. Page, 1909.

---. Emily Climbs. Frederick A. Stokes, 1925.

---. Emily of New Moon. Frederick A. Stokes, 1923.

---. Emily’s Quest. Frederick A. Stokes, 1927.

---. The Green Gables Letters: From L.M. Montgomery to Ephraim Weber, 1905–1909. Edited by Wilfrid Eggleston, Ryerson, 1960.

---. Letters to George Boyd MacMillan. 1903–1941. George Boyd MacMillan Fonds. Canadiana Héritage, Canadian Research Knowledge Network, Library and Archives Canada, 2020. C-10869, C-10890. heritage.canadiana.ca.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Letters to Scotland: The Complete Collection of the George Boyd MacMillan Correspondence, 1903–1941. Edited by Mary Beth Cavert. Unpublished manuscript, 2020.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985–2004. 5 vols.

Preston, Margaret J. “The Unanswered Prayer.” Seventh-Day Adventist ASTR, Advent Review and Sabbath Herald, 5 July 1887, p. 426, documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/RH/RH18870705-V64-27.pdf.

Price, Elizabeth Bailey. “The ‘Fragrant Minutes’ of Wilhelmina Stitch.” Maclean’s. 1 Sept. 1925, pp. 74–78. The Complete Maclean’s Archive. archive.macleans.ca/issues.

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Doubleday Canada, 2008.

---. “L.M. Montgomery: Scottish-Presbyterian Agency in Canadian Culture.” L.M. Montgomery and Canadian Culture, edited by Irene Gammel and Elizabeth Epperly, U Toronto P, 1999, pp. 89–105.

---. “Subverting the Trite: L.M. Montgomery’s ‘Room of her Own.’” Canadian Children’s Literature/Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 65, 1992, pp. 6–39.

Schreiner, Olive [Ralph Iron]. The Story of an African Farm: A Novel. United Kingdom, Chapman and Hall, 1890, Google Books, google.com/books/edition/The_Story_of_an_African_Farm/TY4nAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

“Susan Marr Spalding,” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. Mar. 2020, Wikimedia Foundation, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Susan_Marr_Spalding.

Waterston, Elizabeth. Rapt in Plaid: Canadian Literature and Scottish Tradition. U of Toronto P, 2001.

“Winnipeg Woman Writer Who Won Empire Renown, Is Dead in London Home.” Winnipeg Evening Tribune, 6 March 1936, no. 57, University of Manitoba Digital Collections, digitalcollections.lib.umanitoba.ca/islandora/object/uofm%3A1816950.

Woster, Emily S. Books in the Library of L.M. Montgomery, 2011. Archival and Special Collections XZ1 MS A094, L.M. Montgomery Collection, University of Guelph. Unpublished document.

---. “L.M. Montgomery: The Reading of a Lifetime.” L.M. Montgomery and Reading, 13th L.M. Montgomery Institute Biennial International Conference, Keynote. University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE. YouTube, uploaded by Robert Drew, 23 June 2018. youtu.be/0tF2Bqk4tuI.

---. “Old Years and Old Books: L.M. Montgomery’s Ontario Reading and Self-Fashioning.” L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley Clement, McGill-Queen’s UP, pp. 151–65.