This paper argues that in Montgomery’s Emily novels books perform functions both related and unrelated to the conveyance of text. Montgomery’s focus on Emily’s interaction with manuscripts and books establishes Emily’s understanding of the shift from private manuscript to commodity text as an aspect of literary professionalism.

Subject areas: reading; authorship; material culture

Emily Byrd Starr’s vocation as a writer has received significant attention in studies of L.M. Montgomery’s Emily of New Moon, Emily Climbs, and Emily’s Quest. Elizabeth Epperly, who refers to the series as a “portrait of the artist as a young girl and woman,” argues that Emily Climbs is specifically about “literary apprenticeship.”1 Ian Menzies, Dawn Sardella-Ayres, and Marie Campbell consider the Emily novels as depictions of the choices available to or forced on women artists,2 while I examine Montgomery’s depiction of Emily’s career as that of a specifically Canadian writer.3 Elizabeth Waterston and Epperly both note the parallels between Emily’s and Montgomery’s own literary tastes and experiences4 and describe the series as the story of Emily learning and developing as a writer. Waterston states the “object of [Emily Climbs], after all, is to explore a creative talent in its chrysalis stage,” while Epperly states that in Emily’s Quest “we see Emily developing her voice independently.”5 Clearly, it is widely accepted that the Emily books form a type of Kunstlerroman, the development of the writer and the particular challenges she faces occupying a significant portion of the novels.

In the opening pages of Emily’s Quest, Montgomery’s narrator suggests that writing is not the natural way to transmit stories: “Born thousands of years earlier [Emily] would have sat in the circle around the fires of the tribe and enchanted her listeners. Born in the foremost files of time she must reach her audience through many artificial mediums.”6 Unlike Cousin Jimmy, who has never written down his poetry and recites it only “when the spirit moves [him]” and generally to no one but her,7 Emily sees herself as composing for reproduction. Cousin Jimmy claims he does not write down his poetry because “[p]aper’s too scarce at New Moon,” but his choice to limit his audience to Emily alone suggests he is not interested in reproduction or transmission and has made a deliberate choice between private and public composition. Because, unlike Jimmy, the “artificial medium” of writing is necessary to Emily, through her manuscripts and publications she creates artifacts—objects whose function is to transmit compositions to a non-contiguous audience. As objects fulfilling their designed function, books are used to transmit information, narratives, and states of mind, to transmit and create meaning (however individuals may interpret “meaning”)—their function is understood and accepted as part of what Bill Brown calls “a discourse of objectivity that allows us to use [objects] as facts.”8 Because books are commodities—products of human labour created and reproduced for sale in the market9—books may be purchased and used for purposes outside of the author’s control. That is, they may be things—material artifacts considered independently of their designed function—rather than objects. Emily’s awareness that books can transmit and store meaning as fetishes, taboos, and archives is instrumental to her learning to treat her own writing as a commodity. To be a successful writer she must learn to produce commodities that are saleable on the market and to accept that, once sold, those commodities may be used by purchasers for functions suited to their own needs rather than in accordance with authorial intent. Emily must learn to balance self-expression with marketability and accept the role of purchasers in creating their own meanings for her works.

In the trilogy, Montgomery depicts Emily’s development from writing only for herself and her father through accepting the scrutiny of her writing by critical readers to growing professionalism and success. As Emily moves through these stages, her relationship with the products of her pen changes; she moves from regarding her writing as private to preparing it consciously for commodity publication. By the age of thirteen, Emily has already attempted publication, unsuccessfully, and the end of Emily of New Moon shows her preparing to merge private and public writing as she begins “to write a diary, that it may be published when I die.”10 References to potboilers and to steps achieved on the Alpine Path in Emily Climbs and Emily’s Quest further suggest that Emily makes a deliberate choice to enter a marketplace with her writing and to suit her production to the market’s demands. As Waterston puts it, “The third book in the Emily series … records the details of inspiration, revision, refinement, submission, rejection, subjugation to some of the formulas of publishers, and finally acceptance for publication.”11 Montgomery’s depiction of Emily’s relationship to material books and of her interaction with them as archives and fetishes indicates that Emily sees her own writing as a potential commodity and her published work as beyond her control from early in her life.

The Book as Fetish

Because Emily feels that writing is a necessary part of her self, as a child she transforms her manuscript, as sociologist Alessandra Pozzi puts it, “from an inert object, almost into a being a relationship may be forged with.”12 Thus, immediately after her father’s death, when she burns the yellow account book full of “all the little things she had written and read to Father” to prevent Aunt Elizabeth from reading it, “[i]t seemed as if part of herself were burning there,” and she perceives the book as potentially alive: “[s]he watched the leaves shrivel and shudder, as if they were sentient things.”13 Recalling this book later, Emily writes, “it seemed just like a person to me.”14 This anthropomorphizing of the book containing her private writing, her manuscript, is one of many instances in the Emily novels in which books have roles or functions that, as Brown puts it, “exceed[] their mere materialization as objects or their mere utilization as objects”15; that is, they are more than artifacts with a particular function. Brown states that “the thing really names less an object than a particular subject-object relation” and that “[w]e begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us.”16

Pozzi notes that the book can be fetishized because “it is a medium that involves different senses,”17 and this involvement of the senses forms an integral part of young Emily’s experience of reading. When, in one of her letters to her father, she describes her reading from the New Moon bookcase, her account of the books’ contents is mixed with physical description of the volumes: Thompson’s Seasons [sic] is a “little curly black-covered book,” and Travels in Spain [sic] has “lovely smooth shiny paper.” There are others that she doesn’t like the feel of because “[t]he paper is so rough and thick it makes me creepy.”18 As a student in Shrewsbury, Emily finds in the bookstore that “the aroma of books and new magazines was as the savour of sweet incense in her nostrils”—echoing a phrase Montgomery uses in her journal19—and when she borrows a book from Mrs. Kent, the narrator draws attention to Emily’s awareness of its material aspects: the “old copy” has “a musty, unaired odour” from having been shut up in a box.20 Emily’s sensory response to books is a response to the book as a thing—it is independent of the textual content—but it nevertheless constitutes an experience of books as conveyors of meaning or experience. As Brown writes, “You could imagine things ... as what is excessive in objects, as what exceeds their mere materialization as objects or their mere utilization as objects—their force as a sensuous presence or as a metaphysical presence, the magic by which objects become values, fetishes, idols, and totems.”21

This focus on the materiality of books complicates the notion of what it means to read a book. When Emily buys herself a set of Parkman with the money she earned from “The Woman Who Spanked the King,” her first publication in “a New York magazine of some standing,” we learn that it is “a much nicer set than the prize one” that she failed to win—a reference to its materiality—and that she still has it in the present of the narrator: “Emily has those Parkmans yet—somewhat faded and frayed now, but dearer to her than all the other volumes in her library.”22 Like the garden magazine in which her first published poem appears, which she “gloat[s]” over,23 these physical books are read as markers of success. That is, they have acquired fetish value, a function outside of or beyond their object status. The copy of the Rubaiyat, “one of Emily’s treasured volumes,” that Ilse throws across the room and breaks fulfills a fetishistic function as a gift from Teddy. The “treasured volume” can perhaps still be read after Ilse throws it, but the narrator’s reference is to its symbolic function rather than the significance of its contents. Indeed, the description of “the leaves [flying] every which way for a Sunday” emphasizes the book as a breakable object rather than a reproducible text24 and suggests that, while still treasured, it may not function well as a book anymore.

While awareness of the fetish function of books is particularly important to the professional writer, Emily is not the only member of the family to regard books as having a fetish value that may be independent of readability. Aunt Laura has “a cherished volume” of Mrs. Hemans’s poems inscribed by an admirer back when “it was the thing to give your adored a volume of poetry on her birthday.” The quality of the poetry does not seem to be relevant to the value of the gift. Mr. Carpenter in fact ridicules the textual contents of the book, and Emily, while asserting “I do like some of [Mrs. Hemans’s] poems,” agrees that “that isn’t great poetry.”25 Montgomery herself similarly expresses affection for books she knew in childhood, such as The Memoir of Anzonetta Peters, despite her negative adult assessment of their contents.26 However, the statement that it was “the thing” to give a volume of poetry as a gift draws attention to another function of the book as a commodity. A volume of poetry, regardless of specific contents, can be read as an expression of adoration when used as a gift, and even the possibility of that function is identified as a “thing,” something that can be entified. Brown notes that the word “things” “denotes a massive generality as well as particularities, even your particularly prized possessions,”27 a position that has echoes of Walter Benjamin’s statement with regard to his own book collection that a collector has “a relationship to objects which does not emphasize their functional, utilitarian value” but focuses on “the thrill of acquisition.”28

Emily learns early that most people have a relationship with books that emphasizes books as things rather than objects. Arriving at New Moon and opening the door of the bookcase, Emily is admonished “not to meddle with things that don’t belong to [her]” and responds, “I thought books belonged to everybody.”29 She thus takes books out of the category of “things” in which Aunt Elizabeth places them and attributes different rules of possession and use to them because of their designed function; mere things may be possessed, but books, or at least their contents, she implies, cannot. It is difficult to determine if the taboo on books and the sequestration afforded by the “chintz-lined glass doors”30 at New Moon and by Dr. Burnley’s lockable bookcase are intended to protect the books as things, that is, as commodities with a certain value, or as objects that may be tabooed because of their content and function, or both. It is clear that the lockable features are used to control Emily’s access to text; Aunt Elizabeth has decided that Emily is not to read novels or the medical book she finds so interesting, and therefore she insists that Dr. Burnley’s bookcase must be locked once she learns of Emily’s access to it, though apparently Dr. Burnley himself has seen no reason to prohibit Ilse’s or Emily’s use of his books.31 The attitude toward the material book uncovered by Pozzi suggests that protection of the book as a fetish is an element in how it is stored. Thus, Aunt Elizabeth does not allow Emily access to her father’s books because she thinks Emily “wouldn’t be careful of them,”32 having seen that Emily “put a tiny pencil dot under every beautiful word,” although, from Emily’s perspective, that “didn’t hurt the book a bit.”33 Aunt Elizabeth’s and Aunt Laura’s attitudes to Emily’s writing also make it clear that reading is not valued at New Moon. The sequestering of the books therefore suggests that they are merely other family possessions—things—to be preserved as part of the Murray traditions, not functioning objects, as they are for Emily.

Emily and her father, both writers, might well interact with books in ways that seem inappropriate to Aunt Elizabeth. When fourteen-year-old Emily is finally allowed to have her father’s books, she writes, “It seems to me that a part of Father is in those books. His name is in each one in his own handwriting, and the notes he made on the margins ... I have been looking over them all the evening, and Father seems so near me again.”34 Independently of their original textual contents, the books contain traces of Emily’s father and therefore, in Pozzi’s terms, create “a relationship that lifts the object from being one of many (all the same) to being unique, original and peerless.”35 Emily reads these books not (just) for their literary contents, but for the indirect contact with her father she achieves through handling things he has handled. Her markings in the books both inscribe her own relationship with the book’s textual contents and create a relationship with her father’s markings, thus changing the function of the book from being one of many essentially identical objects purveying a particular text to being a singular object recording both interactions with that text and a personal relationship. Emily is clearly well aware that books may have complex functions for those who own them.

The Book as Repository

Another step in Emily’s learning the multiplicity of relationships with commodity texts is her experience of books as repositories. Emily’s “Jimmy books” in particular suggest her knowledge that it may not be the book itself that has meaning but what is put in it by the owner. When Cousin Jimmy gives her the first “big thick blank book” for her twelfth birthday, she takes it with her on her visit to Aunt Nancy. In it she writes a description of the view of Priest Pond and descriptions of Aunt Nancy and Caroline, as well as getting out of bed at night to write lines of poetry in it.36 She does not bring Aunt Elizabeth’s gift, a dictionary, with her to Aunt Nancy’s, but she acknowledges that its contents are important to her ongoing improvement as a writer: by using it she expects her to improve her spelling and avoid misusing words such as “ween.”37 While Cousin Jimmy’s gift supports her desire for self-expression, Aunt Elizabeth’s gift will help her progress toward meeting external standards as required for marketability. In Emily’s Quest, the role of the Jimmy book as Emily’s repository of ideas is specified: Emily describes the books as a “hodge-podge of description and characters and ‘bits.’” In the same paragraph she notes that Cousin Jimmy gives her a new notebook “[e]very time I pass a new milestone on the Alpine path.” The stack of Jimmy books represents the road Emily has travelled to her status as a “well-known and popular contributor”38 to magazines. The books are both the containers of her material for producing commodity texts, like the notebooks Montgomery kept herself,39 and the markers of her successful use of the material. While each of Emily’s Jimmy books is unique in textual content, containing original work of different genres and different works, notes, and ideas—a general archive of material that may be developed into specific texts intended for other readers—they are identical in outward material form. The exterior cannot, therefore, create any expectation or generate knowledge about the contents, as is illustrated when Emily shows her own writing to Mr. Carpenter and accidentally gives him her non-fiction rather than her fiction to read, not being able to tell the books apart at a glance.40

Furthermore, because of their physical form, the codex, books are capable of containing other kinds of records than the text. In one of her letters to her father, Emily records her interest in Aunt Nancy’s “big parlor Bible,” which contains “pieces of dresses and hair and poetry and old tintipes [sic] and accounts of deaths and weddings.”41 In this the Bible resembles Montgomery’s scrapbooks, which contain all of those items.42 A reader of Aunt Nancy’s Bible may access the sacred text, the inscribed information, other written or printed material, and non-textual information, such as fabric and photos. The possibility thus exists of reading the date of a wedding in the handwriting of a family member, seeing a tintype representing the couple, reading a newspaper clipping containing an account of the wedding with a description of the bride’s dress, and handling a piece of the dress described in the newspaper account and represented in the tintype. The act of reading is not limited to the text of the Bible and includes tactile elements such as Emily records in her encounters with the New Moon books. Indeed, it is not clear that this particular Bible has ever been read for its text. Emily’s account of her experience with Aunt Nancy’s Bible details her awareness, even at this early age, of books having a function or value outside of or beyond their designed function.

The nexus of book as object and book as thing—text and archive, commodity and fetish—is exemplified in Dean Priest’s copy of Jane Eyre. When Dean rescues Emily from her fall over the bank, he places the aster she had been reaching for and subsequently trampled “between the leaves of an old volume of Jane Eyre, where he had marked a verse—All glorious rose upon my sight / That child of shower and gleam.”43 Dean’s choice to preserve the aster next to a verse he had already marked in an old volume suggests that he associates Emily with pre-existing textual knowledge and then reads her into that text. First, he associates the aster with her because of her passionate desire for and subsequent rejection of it;44 in putting the aster in this particular volume, he associates her with the narrator Jane Eyre, a woman who writes her own story, and with the author of that story, Charlotte Brontë. Because Montgomery’s narrator specifies the precise textual point at which Dean inserts the aster—Rochester singing to Jane the evening after she agrees to marry him—it seems he further associates Emily with romantic love for a much younger woman and with the rainbow pursued by the speaker in the song, which perhaps obliquely references his designation of her as “my Star of the Morning.”45 We might also say that he thus attempts to enclose Emily within a narrative he has already interpreted by placing and inevitably flattening the flower in the volume. Lesley D. Clement makes a similar point about Dean’s desire to constrict Emily, arguing with reference to Dean’s selection of pictures for the Disappointed House that “Dean would keep Emily enclosed in a gilded frame as if she were some iconic beauty from the past.”46 Dean’s Jane Eyre performs the same function as Aunt Nancy’s family Bible, becoming a receptacle for ephemera associated with experience, but with the addition of an association with a particular moment in a particular text. Dean’s Jane Eyre therefore becomes (at least) two objects—both a book used for its original function as a text and a book used for its function as a receptacle or archive. This archive, while material, is not itself a commodity, being of value only to Dean himself.

Preparing Text for the Market

While Dean’s use of Jane Eyre as an archive is tied to its precise organization as a text, Mrs. Kent’s interaction with text focuses on the transmission of information, illuminating the distinction between commodity texts and other texts. When Emily finds a sealed letter in a book she borrows from Mrs. Kent, she assumes it has resealed itself after having been opened and then placed in the book.47 After Emily brings it to her attention, Mrs. Kent’s emotional health is restored by her reading of the letter, which is from her long-deceased husband, but she tells Emily, “No eyes but mine must ever see it,”48 making the letter, like the child Emily’s yellow account book, a fetishistic or sacred object. However, she offers to tell Emily the contents. She does the same with reference to Teddy’s letter to Emily expressing his love, which she removed from its envelope so that Emily would not receive it. Although she has burned the letter, she says, “I can tell you what was in it.”49 If transmission of a version of the textual contents does not rely on access to the text or even on the continued existence of the text, the description of Emily at the beginning of Emily’s Quest as a storyteller and of modern methods of publication as creating “artificial” products50 is reified in this climactic scene. Since information in itself can be shared independently of its material textual embodiment, the author-created text must be the primary commodity element of a publication. This explains Emily’s need to control access to her manuscripts. As producer of the text, she must decide when it is ready to be seen by others and when it is marketable.

Emily’s right and ability to decide when her writing is ready for viewing by others is shown more explicitly in the Emily books through scenes in which Emily chooses to burn her manuscript material. Emily first does this as way to protect the fetish manuscript from profanation, but she progresses into doing so as an act of literary judgment. When Aunt Elizabeth finds Emily’s yellow account book and asserts, “I have a right to read your books,” Emily snatches it from her and burns it herself, saying, “I won’t let you—or anybody—see it.”51 She then realizes, “She could never write [the things in it] again—not just the same,”52 understanding that this precise text cannot be reconstructed. When Miss Brownell tries to burn Emily’s poems after reading bits of them aloud to the class, Emily wrests them from her, feeling “they should not get her poems ... no matter what they did to her.”53 However, after the experiences of her visit to Aunt Nancy, she rereads those same poems and burns many of them herself, being “ashamed of them” and finding some of them “positively silly.”54 She continues to burn poems “[e]very time she read her little hoard of manuscripts over” and “unaccountably” found some “fit only for the burning.” Thus, her assessment of them changes as she herself changes and learns—as the narrator puts it, she outgrows them.55

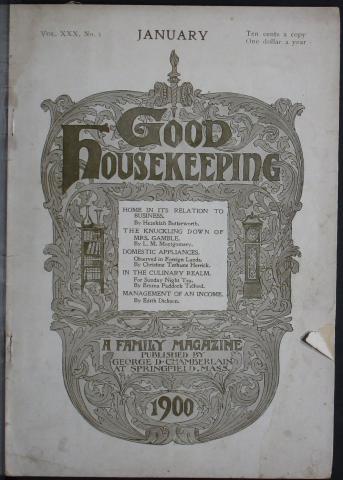

Despite her early exercise of discrimination, when she later is unsuccessful in finding a publisher for A Seller of Dreams, her first attempt to write a novel, Emily reflects that she cannot rely solely on her own literary judgment: “No writer, so she had been told, was ever capable of judging his own work correctly.”56 If she is to be writer, she believes, some of the assessment of her work must be external. Emily is given early encouragement by her father, by Father Cassidy, and by Dean Priest to continue writing, but when Mr. Carpenter asks to see her manuscripts, she feels that “her whole future career ... [is] hanging on his verdict,”57 as she accepts that he is able to give her an accurate assessment of the public value of her work. His encouragement is one of the factors in Emily’s dedicating herself professionally, even though some of what he reads (her sketch of himself, for instance) was not intended for an audience. Emily understands that education drives her literary judgment and is essential to her career preparation, so when she believes Aunt Elizabeth will not allow her to go to high school in Shrewsbury she plans to “work and study at New Moon,” thinking that “another year with Mr. Carpenter would do a great deal for her” on her Alpine Path.58 Her desire for education echoes the feeling Montgomery expressed when she was planning to attend Dalhousie University: “I am anxious to spend a year at a real college as I think it would help me along in my ambition to be a writer.”59

Emily’s growing sense of what professional production requires is recounted over the course of Emily Climbs, as while attending high school Emily makes regular strides in her efforts to move text from the private to the public sphere, learning to deal with rejection by seeking alternative markets and to accept loss of control of the commodity text as a fact of professional life. In this her practice reflects Montgomery’s, who notes in her journal that friends “do not realize how many disappointments come to one success.”60 When Emily’s submission of “Owl’s Laughter” to the high-school paper The Quill is rejected, she sends the same poem to a garden catalogue, where it is printed. A printer’s error in the published text that “made the flesh creep on her bones” and that remains when the poem is reprinted in the Shrewsbury Times draws attention to the author’s inability to maintain the integrity of her text once it has left her hands. Emily knows that the multiple iterations, physical embodiments, and contexts of any commodity text are beyond the control of the author, and thus the author’s decision to submit a manuscript must be based on an acceptance of possible variation.61 Even manuscripts returned to the author’s control may have been changed by readers: when Emily’s manuscript story “Golden Hours” is returned, it is “all dog-eared and smells of tobacco” and therefore can no longer perform its intended function as an object to be offered for sale.62 By choosing to recopy it rather than burn it, Emily creates a new object with still unknown commodity value but at least suitably prepared for the market, a further illustration of the increasing professionalism of her attitude. Her understanding of her work as a commodity is most explicitly demonstrated in the writing of The Moral of the Rose, which she produces, rather in the manner of a production line, one chapter per day as needed to meet the demands of a convalescing Aunt Elizabeth.63 Her attempt to find a publisher is also described as particularly professional, as she retypes the manuscript several times and “work[s] doggedly through a list of possible publishers,”64 as Montgomery reported doing with the manuscript of Anne of Green Gables, actions which underline her understanding of publisher expectations about submissions and of the range of the market.65

Emily’s view of herself as a professional writer who must prepare work for the judgment of the market is, as noted above, also clear in the case of A Seller of Dreams, which she sends to three publishers before showing it to Dean. She burns the manuscript after hearing Dean’s negative assessment of it even though she believes that it has market value: “Not quite the wonder-tale she had fancied it, perhaps; but still a good piece of work.”66 As she watches the flames “murderously” consuming the sheets, she recalls burning her account book, and Montgomery uses almost identical sentences to describe Emily’s feelings as a child and as an adult: “She felt as if she had lost something incalculably precious”; “She had destroyed something incalculably precious.”67 As in the burning of her poems, her own judgment has supported her in the burning of this manuscript, but it is actually a misjudgment, overly influenced by Dean’s false statement about its worth. Her own assessment of the novel’s commodity value was correct. When he later reveals his falsehood to her, she again echoes her reaction to burning her account book, saying, “I can never write it again.”68 Even though the original elements of the stories may remain available to her imagination, and her original notes remain in her Jimmy book, she can never write it again “just the same” and therefore create the same commodity, though she may be able to create a different commodity from those elements. Just as each live act of storytelling is unique, each written—and in the term of the narrator of Emily’s Quest, artificial—version of a story is unique and destructible until embodied as a printed text, a reproducible commodity. When Emily uses her hymn book to hide a scrap of paper on which she has jotted some ideas and sketches during prayer meeting, she wants these unfinished pieces to remain hidden “because there was in them something of dream and vision which would have made the reading of them by alien eyes a sacrilege.”69 That is, these pieces have not yet been subjected to her literary judgment and still have a value arising from the sense of inspiration. Like the writing she protects from Aunt Elizabeth and Miss Brownell, these sketches have not been prepared for other eyes and may not ever be developed in a form Emily is prepared to show others.

Emily’s increasingly professional literary judgment of texts, exercised for instance when she finds a copy of the poem that Evelyn Blake plagiarized, “A Legend of Abegweit,” and thinks that Evelyn had left out “the two best verses,”70 is the mechanism for the shift from private to public, manuscript to commodity. Her attitude to the publication of her own texts changes as she matures; as Epperly states, Emily moves from “apprentice” to “skilled worker,”71 terminology that focuses on the skilled production rather than artistic inspiration aspect of writing. Even as a child, while she is tenacious in protecting her manuscripts from uninvited scrutiny, Emily readily volunteers the information that she is a writer and intends to make writing her profession. When thirteen-year-old Emily eagerly submits a manuscript poem to the Charlottetown Enterprise, keeping it a secret from Teddy only because “she didn’t want to spoil the dramatic surprise” when she showed him the verses in print, she is hurt that the editor “didn’t think it good enough to print,” but within a year she cannot imagine “how she could ever have thought it any good.”72 As the narrator notes, such re-evaluations become routine to Emily, “fairy gold” turning to “withered leaves,”73 with a possible double meaning in “leaves.” It seems that Emily’s re-evaluations are based on a personal standard reflecting an increasingly sophisticated literary judgment, a significant step in her preparation for a writing career, as she needs to assess accurately the marketability of her work. For instance, when Emily has just finished her first draft of A Seller of Dreams, she is momentarily disheartened by seeing the completed manuscript through Aunt Elizabeth’s eyes as “a mere heap of scribbled paper”74—not an inspired work or a potential commodity but simply used paper that does not necessarily contain any information or convey any meaning.

The transition from manuscript to commodity text (book, magazine, newspaper) is dependent on the assessment of a commercial intermediary, the editor. Therefore, the producer of a singular text must be able to calculate the point at which it can be submitted for possible commodity reproduction without undue risk of rejection and of the pain arising from rejection. Emily assumes, as does Janet Royal, that factors beyond the inherent quality of the text may affect the commodity value of a submission. Miss Royal warns her that remaining in Prince Edward Island may hamper her career, as editors will judge her partly on her location, and, later, when Emily has “settle[d] down to a tepid existence of pot-boiling,” warns her that she is “getting into a rut,” causing Emily to wonder if The Moral of the Rose would already have been published if she had established herself in New York and developed professional connections.75 Dean’s honest comments on A Seller of Dreams and The Moral of the Rose similarly focus on Emily’s works as commodities that must find the appropriate market. He tells Emily of A Seller of Dreams, “You would have found a publisher eventually—and it would have been successful.”76 When The Moral of the Rose is published, he describes it as “good, creative work.”77 She has written, as Epperly describes it, “a good, popular novel.”78 In doing so, Emily achieves success in the professional métier that her diary entries at the beginning of Emily’s Quest describe: earning a living and progress through rejection, revision, and publication in successively more reputable venues.79

Technological reproduction of text makes manuscript works that were originally accessible only to the author or to readers co-located with the manuscript available to an indeterminate and uncontrollable readership, so Emily’s relationship with the books she encounters and her experience as a published author specifically draw attention to the lack of authorial control once a book becomes a commodity. Even in her manuscript reading of The Moral of the Rose at home, her family attaches meanings to the text that Emily did not intend: they think one her characters “is too much like old Douglas Courcy,” whom Emily protests she does not know.80 They also think Emily can change the text now to suit their preferences in whiskers or eye colour, not accepting an author’s right to control the text and not understanding Emily’s feeling that the characters have an existence she does not fully control.81 The possibility of a variety of relationships with the text becoming available through publication is made explicit in the account of the contradictory reviews The Moral of the Rose receives, which suggest that each reader has read a different book. While the reviews are of course primarily responses to the text rather than to the physical object, there is an inevitable material aspect of the reviewer’s process, having to do with the physical, personal, and educational circumstances that inform each reviewer’s response. As well, what Gérard Genette calls the peritextual elements of the books, such as author name, title, and illustrations,82 direct the reviewer to particular assumptions about genre and audience, and the reviews themselves as epitextual elements “not materially appended to the text within the same volume but circulating, as it were, freely, in a virtually limitless physical and social space” affect the book’s circulation as a commodity. Genette claims that “a text without a paratext does not exist and never has existed” because “the sole fact of transcription—but equally, of oral transmission—brings to the ideality of the text some degree of materialization, graphic or phonic, which … may induce paratextual effects.”83

Readers who acquire the mechanically reproduced commodity text, whether for its object function as reading material or for some other reason, each do so in a unique historical and material context. As subsequent readers access that commodity text, it continues to accrue individuality through temporal position, physical change, and physical location. That is, once it has been handled, the commodity text is never only a technological reproduction. Benjamin refers to this uniqueness in his discussion of his book collection when he describes what attracts a collector to a particular item: “The period, the region, the craftsmanship, the former ownership—for a true collector the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object.”84 Even for the original owner of a book, the sales slip that is placed between the pages, the splash of coffee that obscures a few letters, or the tearing of a page marks the book in such a way as to recall other objects (the new shoes itemized on the sales slip), emotions (the startled reaction to a ringing phone that caused the coffee spill), and events (the slide on ice in which the book was dropped and damaged) that become part of the text for the owner. As “[t]he presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity,”85 to the extent that each copy of a commodity text becomes an original by marking or staining or by acting as a receptacle or as a fetish or memoir, each gains authenticity. Therefore, when authors prepare texts for the market, they are preparing to hand over the power of creation of a new object to the purchasers, both the publisher that purchases the text and the purchasers of copies of the commodity text. Emily’s early protective attitude to her manuscripts is thus justified. As singular texts, they remain hers. They cannot be changed without her approval. Making her productions publicly available allows purchasers to make what changes they please, whether she likes that or not, so she must accept all commodity functions of her texts to survive in the literary marketplace.

Conclusion

In this series, then, while books may contain and tell and enact stories in their textual contents, those literary contents are only one aspect of the book, as archival and repository functions, fetishization, and taboo dominate interaction with the material book. Emily’s relationship with physical books reflects the full range of these functions, as she fully immerses herself in both the production and the consumption of books as commodities, moving from protecting her manuscripts to selling them while ascribing personal value to experiences of particular copies of books. In presenting Emily’s interaction with books across this range, Montgomery draws attention to the commercial aspect of the career that Emily has chosen based on her expressed need to write. Emily’s progress from writing letters to her father to being a professional writer who is warned about “getting into a rut”86 takes her through a comprehensive experience of the ways singular texts and commodity texts can be experienced and depicts the writer’s learning curve—moving from personal, perhaps inspired, expression through knowledge of readerships and reading practices to acceptance of the ultimate severing of subject from object, of writer from book.

About the Author: E. Holly Pike is associate professor of English at Grenfell Campus, Memorial University, where she teaches literary history, women writers, and children’s literature. She has given many conference presentations on L.M. Montgomery and has published on Montgomery’s works in a number of collections, including L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys (ed. Bode and Clement) and 100 Years of Anne with an "e" (ed. Blackford). She has also published on Elizabeth Gaskell and Jane Austen, and is on the editorial board of the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies.

Banner image derived from The Book News Monthly. September 1999. KindredSpaces.ca, 910 SI BNM 1909.

- 1 Epperly, Fragrance 145, 169.

- 2 See Sardella-Ayres, “Under”; Campbell, “Wedding Bells”; Menzies, “Moral.”

- 3 Pike, “(Re)Producing.”

- 4 Waterston, Magic Island 130; Epperly, Fragrance 200. See also Pike, “Heroine,” and MacLulich, “Literary Heroine” and “Portraits.”

- 5 Waterston 130; Epperly, Fragrance 189.

- 6 Montgomery, EQ 2.

- 7 Montgomery, ENM 67, 143.

- 8 Brown, “Thing Theory” 4.

- 9 This definition is based on both Marx’s Capital and the OED: “A commodity is, in the first place, an object outside us, a thing that by its properties satisfies human wants of some sort or another” (Marx 29); “If then we leave out of consideration the use-value of commodities, they have only one common property left, that of being products of labour” (31); “3.b.A thing produced for use or sale; a piece of merchandise; an article of commerce …” (“Commodity”).

- 10 Montgomery, ENM 302–3, 339.

- 11 Waterston 141–2.

- 12 Pozzi, “Reflections” 43.

- 13 Montgomery, ENM 47.

- 14 Montgomery, ENM 218.

- 15 Brown 5.

- 16 Brown 4.

- 17 Pozzi 43.

- 18 Montgomery, ENM 98-9.

- 19 Montgomery, EC 115; Montgomery, CJ 1 (7 Oct. 1900): 463.

- 20 Montgomery, EQ 193–4.

- 21 Brown 5.

- 22 Montgomery, EC 262, 263.

- 23 Montgomery, EC 131.

- 24 Montgomery, EQ 109.

- 25 Montgomery, EC 253.

- 26 Montgomery, AP 50–1.

- 27 Brown 4.

- 28 Benjamin, “Unpacking” 60.

- 29 Montgomery, ENM 54.

- 30 Montgomery, ENM 54.

- 31 Montgomery, ENM 224.

- 32 Montgomery, ENM 183.

- 33 Montgomery, ENM 184.

- 34 Montgomery, EC 32.

- 35 Pozzi 42.

- 36 Montgomery, ENM 179, 237, 249, 250.

- 37 Montgomery, ENM, 253, 179.

- 38 Montgomery, EQ 15.

- 39 “I have always kept a notebook in which I jotted down, as they occurred to me, ideas for plots, incidents, characters and descriptions” (Montgomery, CJ 2 [16 Aug. 1907]: 171).

- 40 Montgomery, ENM 337.

- 41 Montgomery, ENM 251.

- 42 See Epperly’s Imagining Anne.

- 43 Montgomery, ENM 272.

- 44 Montgomery, ENM 266.

- 45 Montgomery, ENM 272.

- 46 Clement, “Visual Culture.”

- 47 Montgomery, EQ 194.

- 48 Montgomery, EQ 196.

- 49 Montgomery, EQ 198.

- 50 Montgomery, EQ 2.

- 51 Montgomery, ENM 47.

- 52 Montgomery, ENM 48.

- 53 Montgomery, ENM 166.

- 54 Montgomery, ENM 282.

- 55 Montgomery, ENM 303.

- 56 Montgomery, EQ 50.

- 57 Montgomery, ENM 331.

- 58 Montgomery, EC 79.

- 59 Montgomery, CJ 1 (20 Apr. 1895): 266.

- 60 Montgomery, CJ 1 (8 July 1896): 323.

- 61 Montgomery, EC 131, 154. Another example of authorial lack of control is the misprint of “sardines” for “orchids” in Emily’s account of a wedding for the Times (EC 208–9).

- 62 Montgomery, EC 161.

- 63 Montgomery, EQ 143–4.

- 64 Montgomery, EQ 148.

- 65 Montgomery, CJ 2 (16 Aug. 1907): 172–3. See Pike, “L.M. Montgomery and Literary Professionalism” for a discussion of Montgomery’s writing process.

- 66 Montgomery, EQ 49–51, 53–4, 50.

- 67 Montgomery, ENM 47; EQ 53.

- 68 Montgomery, EQ 97.

- 69 Montgomery, EC 43.

- 70 Montgomery, EC 273.

- 71 Epperly, Fragrance 169.

- 72 Montgomery, ENM 302–3.

- 73 Montgomery, ENM 303.

- 74 Montgomery, EQ 49.

- 75 Montgomery, EQ 310, 149.

- 76 Montgomery, EQ 97.

- 77 Montgomery, EQ 178.

- 78 Epperly, Fragrance 189.

- 79 See particularly EQ chapter 2.

- 80 Montgomery, EQ 147.

- 81 Montgomery, EQ 146.

- 82 Genette, Paratexts, 1.

- 83 Genette, 3.

- 84 Benjamin, “Unpacking” 60.

- 85 Benjamin, “Work of Art” 220.

- 86 Montgomery, EQ 149.

Works Cited:

Arendt, Hannah, editor. Illuminations. Translated by Harry Zohn. Schocken, 1969.

Benjamin, Walter. “Unpacking My Library.” Arendt, pp. 59–67.

---. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Arendt, pp. 217–51.

Brown, Bill. “Thing Theory.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 28, no. 1, autumn 2001, pp. 1–22.

Campbell, Marie. “Wedding Bells and Death Knells: The Writer as Bride in the Emily Trilogy.” Rubio, pp. 137–45.

Clement, Lesley D. “Visual Culture, Storytelling, and Becoming Emily: An Illustrated Essay.” Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, 2020 Vision Forum. https://journaloflmmontgomerystudies.ca/vision-forum/becoming-emily-illustrated-essay.

“Commodity.” OED Online, Oxford UP, Sept. 2020, www.oed.com/view/Entry/37205.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery's Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. U of Toronto P, 1992.

---. Imagining Anne: The Island Scrapbooks of L.M. Montgomery. Penguin Canada, 2008.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge UP, 1997.

Menzies, Ian. “The Moral of the Rose: L.M. Montgomery’s Emily.” Canadian Children’s Literature/Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 65, 1992, pp. 48–61. CCL/LCJ, https://ccl-lcj.ca/index.php/ccl-lcj/article/view/4744.

MacLulich, T.D. “L.M. Montgomery and the Literary Heroine: Jo, Rebecca, Anne, and Emily.” Canadian Children’s Literature/Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 37, 1985, pp. 5–17. CCL/LCJ, https://ccl-lcj.ca/index.php/ccl-lcj/article/view/1822.

---. “L.M. Montgomery’s Portraits of the Artist: Realism, Idealism, and the Romantic Imagination.” English Studies in Canada, vol. 11, Dec. 1985, pp. 459–73.

Marx, Karl. Capital. 1887. Translated by Samuel Moore and Edward Aveling. Dietz Verlag, 1990. web.b.ebscohost.com

Montgomery, L.M. The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career. 1917. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 1997.

---. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889–1911. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston. 2 vols. Toronto: Oxford UP, 2006.

---. Emily Climbs. 1925. Seal Books, 1983.

---. Emily of New Moon. 1923. Seal Books, 1985.

---. Emily’s Quest. 1927. Seal Books, 1983.

Pike, E. Holly. “The Heroine Who Writes and Her Creator.” Rubio, pp. 50–7.

---. “L.M. Montgomery and Literary Professionalism.” 100 Years of Anne with an “e”: The Centennial Study of Anne of Green Gables, edited by Holly Blackford. U of Calgary P, 2009, pp. 23–40.

---. “(Re)Producing Canadian Literature L.M. Montgomery’s Emily Novels.” L.M. Montgomery and Canadian Culture, edited by Irene Gammel and Elizabeth Epperly. U of Toronto P, 1999, pp. 64–76.

Pozzi, Alessandra. “Reflections on the Meaning of the Book, Beginning with Its Physicality: Instrument or Fetish?” Italian Sociological Review, vol. 1, no. 2, 2011, pp. 38–46.

Rubio, Mary Henley, editor. Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery, Essays on Her Novels and Journals. Canadian Children’s P, 1994.

Sardella-Ayres, Dawn. “Under the Umbrella: The Author-Heroine’s Love Triangle.” Canadian Children’s Literature/littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 105–106, spring/summer 2002, pp. 100–13. CCL/LCJ, https://ccl-lcj.ca/index.php/ccl-lcj/article/view/3849.

Waterston, Elizabeth. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery. Oxford UP, 2008.