Montgomery’s essays aren’t typically conceptualized as essays: that is, the delightful literary genre which began with Michel de Montaigne. In a hybrid of essay/scholarly article, I read Montgomery’s essays within the essay tradition by considering them in pairings with essays by other essayists, providing a background on the essay, and highlighting the publication mediums of Montgomery’s essays.

Introduction

I’ve learned that I must not enter a used bookstore in search of a particular title or, at least, be too concerned about whether I find it, if I want to experience the true delights of the used bookstore. Unlike the big box bookstores of today, which are overrun with yoga mats and mugs and other things to “gift,” the used bookstore, not yet extinct, is still crammed with those delightful curiosities we call books. The success of this establishment rests on the premise that its patrons possess a certain openness to the unexpected, a mild belief in happenstance. If you’ve ever had the pleasure of being lost in a used bookstore (and I hope you have), you’ll know what I mean. It’s the unlikely faith that, on any given day, you may—if you but look long enough—find the book that seems to leap off the shelf at you and declare, “Here I am! Take me home!” You’ve not so much chosen it, but it has chosen you.

Some years ago, on a lazy afternoon, I happened to be browsing the second floor of a second-hand bookstore when, not one, but two books leapt at me in this way. Sitting side by side in the literature section were Michel de Montaigne’s Essays and one of L.M. Montgomery’s novels. Yet their joint chorus was not “Take us home!” (I already owned a copy of each) but rather “Look at us. Consider us in tandem.” What could I possibly learn from the liminal space between these two disparate writers? One was an aristocrat of the minor landed nobility writing from his château in sixteenth-century France, the other an assistant postmistress writing from her grandparents’ farmhouse in Prince Edward Island in the early twentieth century. A vast expanse of time, space, and experience separating them, theirs was a chance encounter, an accident of names: Montaigne and Montgomery, both mont—two mountains—brought together alphabetically in a used bookstore in Utah.

I wondered if I could find more than a private connection between them—Montgomery, whom I’d studied in an earlier Master’s degree, and Montaigne, whom I was studying in a current one. And then, the secret of their juxtaposition clicked, and the question emerged: had Montgomery read Montaigne? Had I been pressed to explain what I meant, I would have clarified: could Montaigne’s influence be traced in Montgomery’s writing? I recognize now that Montaigne had symbolized, in my mind, the essay itself, so that the question which the arrangement of these writers’ books suggested was ultimately: had Montgomery written essays of her own? (And could I find them?) But first, before I answer those questions, let me ask and answer another: what do I mean by “essay”?

Brief Overview of the Essay

Perhaps more than any other writer, Montaigne could be the metonym for an entire literary genre. Widely regarded as the father of the essay, Montaigne not only coined the term “essay,” he also wrote the first ones, publishing his 107 Essais (or Essays, when translated) over three books in the late sixteenth century,1 which continue to be considered some of the best essays ever written.2 From the French verb essayer, which means “to attempt” or “to try,” Montaigne’s Essais—his attempts—daringly take himself as the subject of his work, as he combines personal anecdotes, quotations from his reading, reflections on the quotidian, and his own humanistic insights. His words wander on the page whichever way his mind leads him, thereby creating a literary “form that is itself intrinsically formless,” as Joseph Epstein writes of the genre generally.3 Though Montaigne quoted his literary predecessors as if he were creating a commonplace book (a personal collection of quotations from one’s reading, organized by subject matter4), he believed the most valuable learning came from reflection on personal experience. He wrote under the premise that “Every man has within himself the entire human condition,”5 meaning, as essayist Phillip Lopate explains, “that when he was telling about himself, he was talking, to some degree, about all of us.”6

Even four centuries later, the personal essay—which Theresa Werner explains is “what most people mean when they consider the essay as a genre”7 and which Emily Donaldson claims is “the original form itself”8—is still characterized by its wandering structure, conversational tone, intimate portrayal of the writer, introspection and timeless reflections, consideration of the everyday, delightful digressions, and making of meaningful connections among disparate things. (As have others before me, I refer to the literary form which began with Montaigne simply as the essay, and make little distinction between the personal and familiar essay.9) Virginia Woolf, a contemporary to Montgomery and an essayist herself, gets to the heart of the essay when she writes: “The principle which controls [the essay] is simply that it should give pleasure … . Everything in an essay must be subdued to that end.”10 Cynthia Ozick explains that “A genuine essay has no educational, polemical, or sociopolitical use; it is the movement of a free mind at play.”11 It’s this sense of pleasure that I’ve used as a guide when searching for Montgomery’s essays among her select non-fiction writing.

Alexander Smith wrote that “The world is everywhere whispering essays,”12 and while he was referring to ideas for the writing of essays, I think the quotation applies equally to the finding of them. They can be discovered in different media of publication, under various names, and in a variety of literary forms. But if essays are at times difficult to identify, then it’s due in part to the confusion of labelling. Those things which are not literary essays (that is, scholarly articles) are often called by the name essay (as are so-called “formal essays” including historical and critical ones13), while genuine (that is, Montaignesque) essays are at times known as something else,14 trends that also appear in Montgomery scholarship.15 (Of course, it’s most helpful to readers when collections of genuine essays include “essays” in their titles for easy identification.) Essays also “take the shape” of other forms—such as letters and newspaper columns—and in some cases are subsequently included in essay collections or anthologies.16

The recognition of essays, then, relies less on a name than upon one’s prior experience of reading personal essays within the essay tradition, and an understanding that these pieces “share the essayistic qualities of personal presence, inward reflection, and intimacy,” as Jenny Spinner notes of inclusions in her recent anthology of essays by women.17 While essays, like used books, can theoretically be found anywhere, it helps to know where they’re likely to be in high concentration. As Norris Hodgins notes, “essays are not usually written in bookfuls.”18

Mediums of Publication

Since the eighteenth century onward, essays have usually first appeared in periodicals, sometimes alongside other forms, other times in periodicals dedicated to the genre, and have been subsequently collected with other essays in essay anthologies and essay collections. “The history of the essay is inextricably entwined with the history of the periodical,” explains J.B. Priestley, a twentieth-century essayist. “Since there have been papers and magazines to write for, all our chief essayists have been ‘periodical writers.’”19 Essays that appear in periodicals can either be occasional, or else can be what James M. Kuist identifies as “periodical essays,” a term he notes “may be applied to any grouping of essays that appear serially.”20 Within her lifetime, Montgomery wrote several dozen non-fiction pieces, many of them stand-alone pieces but also a couple of series, which she began publishing in a variety of Canadian and American periodicals around age sixteen, and continued right up until the decade of her death, a span of about fifty years.

I’ll relieve you of any suspense (now that the scene’s been set) by simply stating that among Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces, I was delighted to find a handful of essays in the tradition which began with Montaigne. However, scholars have often used other labels to identify Montgomery’s essays, referring to them individually, for instance, as “articles” (a term which essayists have conceptualized as being the antithesis of essays21) or only vaguely as “pieces.” Those which I found to most align with the genre of the essay are “My Favorite Bookshelf,” “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery,” a four-part series beginning with “Spring in the Woods,” and a pseudonymous newspaper column, “Around the Table.”22 In these essays, Montgomery’s style is intimate and conversational, often witty and humorous, all characteristics of the literary genre which began with Montaigne. Montgomery also writes about subjects long associated with essayists, including walking, books, and idleness. Though all published in periodicals within Montgomery’s lifetime, her essays were not subsequently collected and republished, leaving them inaccessible to the common reader.

In fact, if I had gone searching for any of Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces (to say nothing of her essays, specifically) in a bookstore, I would—until very recently—have left empty-handed. Unless, of course, I wanted to be weighed down by more than half a dozen various books, most of which contain only a piece or two of Montgomery’s periodical non-fiction, appended as supplementary material to the main text (a heavy load for a scant amount).23 And her essays!—I would only have found these (and it would have had to be in a used bookstore) if there happened to be an “ephemera” box with old periodicals in it: specifically, four issues of the 1911 Canadian Magazine where Montgomery’s four-part series beginning with “Spring in the Woods,” was published; a 26 September 1901 issue of the Halifax Daily Echo with Montgomery’s “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery”; a complete run of the Saturday (and later Monday) editions of this same Echo from September 1901 to May 1902 with “Cynthia’s” column “Around the Table”; and then, the rarest of them all, the unknown periodical in which Montgomery’s “My Favorite Bookshelf” appeared, circa 1917.

Yes, the medium in which an essay appears seems intrinsically connected to whether the piece has a fair chance of being read after its initial appearance (if in a periodical, it may easily be thrown away after a week of two). Is it ironic, then, that my own essay—the one you are currently reading—is being published in a periodical? And an online one at that? Digital!—the most ephemeral of all ephemera, why, it could disappear without a trace (unless it’s subsequently republished in a collection).

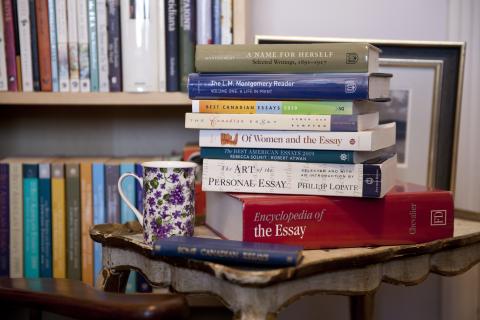

Though a periodical search undoubtedly has its own delights, I for one am relieved I didn’t have to embark on one in order to access Montgomery’s essays. Benjamin Lefebvre, through the archival work of scholars including himself,24 has now collected and published dozens of Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces in two edited collections: The L.M. Montgomery Reader: A Life in Print and A Name for Herself: Selected Writings 1891–1917.25 Within these two volumes, all of Montgomery’s essays to which I’ve referred can be found. The significance of these collections for the essay in Montgomery studies cannot be overstated. In the larger field of non-fiction, essayist David Lazar recently proclaimed, “we seem to have entered The Age of Nonfiction, at least in the Academy,” when several new “nonfiction anthologies” were published which “focused explicitly or implicitly on the essay.”26 With the publication of Lefebvre’s recently edited collections, comprised mainly of Montgomery’s non-fiction, Montgomery scholars and readers too seem to have entered “The Age of Nonfiction.”27

The Current Status of the Essay

In large measure, it seems to be a good historical moment to consider the essay. Anthologies essential for understanding the history of the essay have been published, notably Phillip Lopate’s The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present (1994), Jenny Spinner’s recent recovery work Of Women and the Essay: An Anthology from 1655 to 2000 (2018), and, in the Canadian scene, Gerald Lynch and David Rampton’s The Canadian Essay (1991); in addition, the finest contemporary essays are curated each year in ongoing essay collections like The Best American Essays28 and Best Canadian Essays;29 graduate programs in creative writing offer semester-long workshops on the essay; writing conferences feature panels devoted to the genre;30 and—most significantly—periodicals are publishing essays,31 and collections are being published by individual essayists.32 The essay is not a dusty relic of the Renaissance; it’s a thriving contemporary genre.

Now that readers can just drop by a bookstore or online shop and pick up Montgomery’s essays, there’s a much greater chance they’ll be read. Lefebvre’s collections offer permanence for these pieces in a way not possible when they were available only to the diligent individual willing to comb through microfilm of periodicals, using scrapbooks of Montgomery’s periodical publications as a guide and visiting various archives and other repositories to do so. Montgomery’s essays have never been more accessible. And yet, they remain inaccessible on an interpretative level when they are not regarded as essays.

Scholars have long struggled to conceptualize Montgomery’s essays as essays, treating them instead as one-offs, studying them in isolation from other essays (either by Montgomery or others), and using a variety of labels to refer to them individually; or else, scholars identify these pieces by what they are not, grouping them with Montgomery’s other “miscellaneous pieces.”33 When Lefebvre published several of these in A Name for Herself, he quipped that “rather than call [the] book Not Short Stories and Not Poems,” he has “organized these materials around Montgomery’s creation of a name for herself,”—as these pieces cover a period in which she was still playing with her pen name—as she “earned a living selling work to mainstream periodicals across North America.”34 Unlike Montgomery’s short stories and poetry, which likewise first appeared in periodicals in Montgomery’s lifetime and were later posthumously published in collections, Montgomery’s essays—and her periodical non-fiction in general—haven’t been packaged by genre in their republications. Though A Life in Print and A Name for Herself are comprised mainly of Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces,35 Lefebvre’s stated objectives for these collections are to trace "the evolution of Montgomery’s career and legacy” (The L.M. Montgomery Reader, including A Life in Print), “to demonstrate a facet of her development as an author, and … to take a new look at her major retrospective account of that development” (A Name for Herself).36 This approach follows a more general trend: “The essay,” writes Graham Good in The Observing Self: Rediscovering the Essay “… has remained the ‘invisible’ genre in literature, commonly used but rarely analyzed in itself.”37

Another trend recently emerging in Montgomery scholarship is to refer to some of her writing, collectively, as essays.38 While at first suggesting the beginning of a greater awareness of the essay in Montgomery scholarship, I soon realized that “essays” was being used as shorthand for Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces in general. And while I wouldn’t go as far as Priestley who claimed that “the term ‘essay’ is so elastic that it means nothing,”39 the vast range of Montgomery’s non-fiction periodical pieces could be called “essays” only in the broadest sense of the word, one which has little to do with Montaigne. Though Lefebvre does refer to some of Montgomery’s pieces individually as essays, this naming is inconsistent40 and without an accompanying explanation as to what is meant by this often-misunderstood term.

Ultimately, the chronological arrangement of Montgomery’s periodical pieces in these volumes doesn’t invite the reader to consider them by genre in the way it would have had her essays been gathered together as her short stories and poetry have been, where they can be read alongside each other. A certain amount of recovery work, then, is still required to identify the essay in Montgomery studies. It’s largely up to the reader to “find” Montgomery’s individual essays in these volumes (not unlike looking for a book in a used bookstore, or searching for individual pieces in a microfilmed periodical).

But as G. Thomas Couser observes in his book Memoir, “categorizing works is not the end of genre analysis but its starting point. The goal is not to classify works but to clarify them.”41 Naming is an interpretative act: it cues the reader how to read a text. But it’s only the first step in this further clarifying. Couser continues: “We can’t fully understand what a particular author or story is doing without some sense of the operative conventions, which are a function of its genre.”42 By not recognizing Montgomery’s essays as being part of a genre, scholars have largely overlooked their literary qualities in favour of reading them “in relation to some outside focus” as Good says essays often are used, “to illustrate the author’s views and shed light on [her] work in ‘major’ genres… .”43

Simultaneously, Montgomery’s essays have puzzled scholars for their inexplicable style and subject matter. Without the clarifying framework of genre, the literary possibilities for interpretation are severely limited. With this framework, the possibilities open up, providing an entire tradition with which they can be considered, compared, and clarified. (Could you imagine trying to interpret Anne of Green Gables without understanding it belonged to the literary tradition called the novel, or more specifically, its subgenre, the Bildungsroman?) Understanding that Montgomery’s essays belong to the tradition which began with Montaigne relieves the confusion of how they’ve been read in the past: as “miscellaneous pieces” sitting awkwardly on the sidelines of Montgomery’s oeuvre, gleaned for biographical details, or else used as glosses to her other writing. When essays are read as essays, they become clearer—their focus sharpened—especially as they’re read alongside other essays. And so, I’m presenting Montgomery’s essays with essay pairings. Through these juxtapositions, new meanings, interpretations, and ways to approach these works emerge, like seeing Montgomery’s novel beside Montaigne’s essays in the used bookstore.

Now, I’ll admit, I’m not strictly an academic (even with my two Master’s degrees), nor am I strictly an essayist (though I aspire to be). But I am, like Montgomery, a reader. And, as a reader, I bring my experience of reading essays in the Montaigne tradition as I approach Montgomery’s own writing in this genre. While my academic side is tempted to be systematic and say everything I know about the subject (if only buried in endnotes which no one will ever read), and while I’ve tried to read widely in the essay tradition, in the pairings which follow, I do not claim they are the most similar or even the most suitable; but they are the ones which I’ve happened upon, the ones which have suggested themselves to me. Perhaps this is always the case, but in academia, we feel the need to cover everything (or at least, give the appearance of having done so), to try to ensure there’s no gaping hole we’ve overlooked. An essayist isn’t so much concerned about that. (An essay is, after all, “a form of discovery,”44 which has been my experience as I’ve read and considered Montgomery’s essays alongside those by other essayists.)

But I do feel the need to draw attention to the essay’s relative neglect in academia, that “despite the extraordinary growth of interest in the essay during the past twenty-five years”—this written in 2012—“… the essay has largely been ignored in the world of criticism and theory,”45 and that the essay—grouped with a seemingly leftover category of writing referred to as the “fourth genre,” following poetry, fiction, and drama—isn’t even considered as literature by many academics. (How many individual essays or essay collections, for instance, have you seen appear on reading lists in an English department, to say nothing of course offerings that study the essay as a genre?) Now, there has of course been some scholarly attention directed toward the essay in recent years, largely in the form of academic articles.46 But, still, “only a handful of academic books have been devoted to defining [the essay] or interpreting it”47 during the genre’s recent “growth of interest.” Inexplicably, the essay is largely overlooked and ignored in the academy, and no one seems—or very few seem—to care. In the world of academia, this is tragedy indeed (for if academics do not take the essay seriously, who will?).

And where are all the essayists, you may ask, during this renaissance of the Renaissance genre, while the essay is ironically in the throes of academic neglect? Oh, they’re likely too distracted enjoying the essays they’ve found in used bookstores to bother writing dissertations about them. (Statements on the genre are most likely to be found in their own essays, such as the ones selected for Carl H. Klaus and Ned Stuckey-French’s anthology Essayists on the Essay: Montaigne to Our Time.48) And the situation isn’t likely to change. I have a sneaking suspicion, though I’ve no proof—other than my own experience—that whenever a non-essayist manages to stumble upon the genre—why, they just drop out of academia altogether! After reading a few delightful essays about books, idleness, and walks in the country, the academic decides he or she has been straining too hard with interpretative strategies and methodologies in the pursuit of meaning. One need not work too hard to understand the essay. Besides, it’s much more enjoyable simply to read essays than it is to write scholarly articles about them (which is precisely why I’ve decided to consider Montgomery’s essays from a hybrid essay/scholarly article approach, rather than a straight-up scholarly article). Is it little wonder, then—with all the essayists absent and any would-be essay scholars on the way out—that the essay has received so little scholarly attention to date?

Reading Montgomery’s Essays

The real advantage I see of reading Montgomery’s essays as essays is that I don’t need to concern myself too much with the seeming incongruities in her writing. Oh, I could get all bent out of shape about why she wrote about this, or in that way. Or I can just acknowledge that these are essays and enjoy them (and you can too, reader). Once you read a few essays, you find yourself letting go of the anxieties that had stressed you, and just relax into them.

If I’m worried about Montgomery’s morbidity because she wrote an essay about rambling in a Halifax graveyard in “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery,” I need only pair it beside “[On Westminster Abbey]” to discover that Joseph Addison did the same thing in London nearly two centuries before. If I’m perplexed as to why Montgomery wrote a whole essay about her books in “My Favorite Bookshelf,” I can simply read it alongside “A Shelf in My Bookcase” to see that Alexander Smith did likewise not fifty years prior. If it offends me as a twenty-first-century reader that Montgomery wrote extensively about the domestic in her newspaper column “Around the Table”—and if it further concerns me that she “made stuff up” and signed it “Cynthia”—I need only look to the long tradition of “periodical essayists” who assumed fictionalized personas in their essay series as they gossiped about all sorts of delightfully domestic things.49

And that’s only the subject matter!

Only once these anxieties fade into the flames of a newly lit fire, glowing and crackling with warm anticipation, can one leave one’s solitary desk, loaded with scholarship, and one’s laptop, slowed by its open tabs, a lonesome cursor blinking in a luminescent document, and curl up in some cozy corner—ideally an inglenook—with a book and enjoy these essays as they’re meant to be read: with pleasure.

“My Favorite Bookshelf”

One of life’s little pleasures which essayists commonly fix their attention on is reading, or simply being surrounded by their books. Montaigne, of course, began this tradition with his essay “On Books,” and provided the details of his personal library in another essay.50 While numerous essays have been written on these subjects, including several contemporary to Montgomery’s,51 Alexander Smith’s “A Shelf in My Bookcase” suggested itself to me as a pairing for Montgomery’s “My Favorite Bookshelf,” perhaps because its subject, style, and mood all so whimsically capture the ideal of the “genteel essayist,” a tradition which Montgomery herself is writing into.

Somewhat pejoratively imagined, Good caricatured the genteel essayist as “a middle-aged man in a worn tweed jacket in an armchair smoking a pipe by a fire in his private library in a country house somewhere in southern England, … maundering on about the delights of idleness, country walks, … and old books, blissfully unaware that he and his entire culture are about to be swept away by the Great War… .”52 Women essayists such as Agnes Repplier, a contemporary of Montgomery’s, also wrote “in the style of the genteel tradition,”53 though genteel women essayists were not as common as male ones. (It’s also worth noting that women essayists, in general, were more numerous than has commonly been supposed, as Spinner aptly demonstrates in her recent anthology of essays by women which historically have been overlooked.54) Spinner notes that Repplier’s essays “were popular among turn-of-the-century editors and readers who favored the voice of the bookish, laid-back English gentleman. Even as a woman, Repplier could imitate this voice in order to succeed as an essayist,”55 a voice Montgomery likewise assumes in “My Favorite Bookshelf.”

Though Smith’s “A Shelf in My Bookcase” appeared in Dreamthorp: A Book of Essays Written in the Country56 more than fifty years before Montgomery’s “My Favorite Bookshelf” was published, Dreamthorp was subsequently republished multiple times, including by Montgomery’s own publisher, L.C. Page, in 1907, the year before Anne of Green Gables first appeared. While I’ve seen no direct evidence that Montgomery read Smith’s essay, it’s possible she did read it.57 The publication connection is interesting—the sort of detail an essayist takes delight in.

Montgomery’s “My Favorite Bookshelf” was first “published in an unidentified periodical around 1917,” as Lefebvre notes in A Life in Print,58 though it’s unknown when she wrote it. In contrast to Montgomery’s celebrity memoir, The Alpine Path: The Story of My Career,59 which appeared the same year, “My Favorite Bookshelf” doesn’t make reference to Montgomery’s fame, other than identifying her in the byline as L.M. Montgomery (a pen name which “she also used in her private life,” as Lefebvre points out60), and as the “Author of Anne’s House of Dreams, etc.” When compared with her non-fiction periodical pieces of this period (which were essentially short memoirs recounting her childhood and literary development from the perspective of a now professional writer), the omission of Montgomery’s literary status in the text may seem unusual. And yet, her choice to leave this unmentioned aligns with essayists, who tend to shy away from notoriety (or at least present themselves as doing so).

“My Favorite Bookshelf” itself takes up less than two full printed pages in A Life in Print, and I’ve only found a few references to it in Montgomery scholarship. Those who have mentioned it don’t appear to have conceptualized it as belonging to the literary genre of the essay, but rather have highlighted the piece’s autobiographical components.61 Lefebvre suggests that it “provides readers with a glimpse of Montgomery’s reading life,”62 and Mary Rubio quizzically reflects that it “is so light, so cheerful and wistful, that no one could read it and think that [Montgomery] had ever had a trouble in her life,”63 which of course we know was not the case. Montgomery lost her mother when she was an infant, had a son die at birth, and, in 1917, the Great War was still being fought. But if “My Favorite Bookshelf” is read in the context of the essay—especially the familiar essay that focuses on everyday objects, with a light touch—Montgomery’s subject and stylistic choices are thrown into relief. As my essayist professor used to point out, Charles Lamb (whom Montgomery read64), in his Essays of Elia, never wrote of the tragedy of his mother or the madness of his sister; and, as Lopate notes, “Even in periods of extreme upheaval, the personal essayist tends to cling to the familiar and domestic, the emotional middle of the road—not necessarily because he or she is lucky enough to have been spared tragedy, but perhaps the opposite.”65

Eventually, the genteel essayist, writing on familiar subjects, would fall into disfavour, but in Repplier’s 1918 essay “The American Essay in War Time” she claims, “To write essays in these flaming years, one must have a greater power of detachment than had Montaigne or Lamb.’”66 Montgomery, leaving the unhappy life she recorded in her journal and her imposing position of being a world-famous writer, delves into the delights of her books and reading in her essay “My Favorite Bookshelf.”

The pairing of Montgomery’s “My Favorite Bookshelf” with Smith’s “A Shelf in My Bookcase” revolves around the delight of the imagined reader visiting these personal libraries. Imagine what could be gleaned about a person from the books they keep, how they arrange them, and their condition. Smith draws attention to “a certain shelf in the bookcase … in the room in which I am at present sitting”67 and Montgomery to “the shabby old bookcase in the corner by my desk.”68 I imagine them—as I hope you imagine me—at their desks in the act of writing, books nearby. Curiously, they’ve arranged these shelves similarly: Smith’s consisting of his “favourite volumes”69 and Montgomery’s, her “pets and darlings.”70

Through the condition of their books, both Smith and Montgomery represent themselves as readers, which is in sharp contrast to the antiquarian collector. (“If you only want to read them, why are some of them bound in morocco and half-calf and other expensive coverings?” quibbles A.A. Milne in “My Library.”71) As I read, I have the pleasure of seeing Smith’s worn books, inside and out, not only as I would if I were looking at them on his library shelf, but also as he envisions them in his own mind. He describes his volumes as “somewhat the worse for wear,” explaining that “Those of them which originally possessed gilding have had it fingered off, each of them has leaves turned down, and they open of themselves at places wherein I have been happy, … each of them has remarks relevant and irrelevant scribbled on their margins.”72 Smith focuses on the physical condition of his books, which shows what kind of reader he is, while Montgomery only refers to the overall appearance of her bookcase as “shabby.”73 But she draws attention to the physical importance of these books—and herself as a reader—when she writes that this bookcase “is the only one I would make a desperate effort to save if the house were on fire. … New copies of them would not take their place—I must have these identical books which I have read and reread so often that they have acquired an aroma and personality all their own … .”74

As each essay unfolds, Smith and Montgomery represent themselves as indiscriminate, unpretentious, eclectic readers, who read (as essayists do, and hope in turn are read) for the pleasure of reading. Both depict the books on their special shelves as “friends,” Smith using his entire first paragraph in setting up this metaphor before claiming that his “favourite volumes cannot be called peculiar glories of literature; but out of the world of books have I singled them, as I have singled my intimates out of the world of men.”75 Montgomery more directly states, “These books are my friends; the books in the other bookcases are merely agreeable acquaintances.”76 While Smith bars the literary heavyweights from his “special shelf”77 (“Milton is not there, neither is Wordsworth; Shakespeare … [is] on the shelf where the mighty men repose”78), Montgomery indiscriminately claims, “There are no class distinctions in my pet bookshelf. If a book has the subtle, intimate, indefinable appeal for me which a book-friend must have I care not whether it come in rags or tags or velvet gown, whether its author be known or unknown, new or old. It is of kin to me and I gladly hail the relationship.”79

Smith ruminates on several specific books in great detail on his “special shelf,”80 while Montgomery catalogues the books on her “pet bookshelf” by subject matter, without naming a single title or writer. Smith’s consideration is for depth; Montgomery’s, for breadth, showcasing (in an unassuming way) her wide range of reading, as essayists often possess. Within her “motley collection”81 Montgomery claims she has “a book for my every mood,”82 which she then spends the majority of her essay chronicling. “Here is the little book of modern verse,” she writes, “into which I like to dip when my mind feels dusty and commonplace and longs for a pleasant bit of starfaring; and here is the Great Poet to whom I turn when I need consolation for some deep grief or expression for some mighty emotion,” and so on.83 In like manner, she lists the travel book, the quiet meandering book, the girl’s book, the boy’s book, the latter “which is to me as manna in the wilderness when I grow tired of ordering my household … and desire wildly to start out with a battle-axe, or go hunting for buried treasure, or shooting grizzly bears”—a garden book, a historical novel, a fat biography, history, and “essays for the literary, bookish mood; and a book about cats because I love cats in every mood,” winding it up with “a most jolly volume of gruesome, horrible, delicious ghost stories … .”84 Delightful! (And did you catch her reference to the essays?85)

The physicality of the books on Montgomery and Smith’s shelves is central to their essays, as they give an occasion to reflect on their reading. While Smith delves deep into the contents of his books and his thoughts about reading them, Montgomery does not dip into her own books, either physically or metaphorically, but remains on the surface. In a similar way, her essayistic reflections do not run deep in this piece; the pleasure for the reader is in the browsing … which is reminiscent of another favourite pastime of the essayist: rambling.

“A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery”

Montgomery—writing as “M.M.”—begins “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery” by announcing, “As a general thing, a graveyard is not considered a cheerful spot for a ramble!”86 With the word “ramble,” she invokes the long tradition of essaying about walking, particularly when it’s referred to as rambling, as this serves a dual meaning for perambulating while the writer’s words wander on the page, representing the essayist’s thoughts:87 “My thoughts fall asleep if I make them sit down,” Montaigne wrote. “My mind will not budge unless my legs move it.”88 Though there’s a long tradition of essaying about country walks—including Montgomery’s own four-part series on the woods—there’s also a healthy representation of urban walking, particularly in and around London.89 Newly arrived in Halifax for her several months’ stint at the Halifax Daily Echo where she’s been hired as a proofreader, Montgomery likewise chooses an urban scene.

Montgomery scholarship is silent about “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery,” though Lefebvre observes in the headnote accompanying it that “Montgomery would draw on parts of this essay to describe Anne’s impressions of a Kingsport cemetery in … Anne of the Island,”90 the novel which depicts Anne’s time at Redmond College, loosely based on Dalhousie University in Halifax. The cemetery scene occurs soon after Anne’s arrival in the city. Unlike Anne, who would receive a full four-year B.A., Montgomery only had one year of study at Dalhousie, which she completed five years before she wrote this essay. Like many women essayists before her,91 Montgomery did not have the same advantages of schooling as her male counterparts, but what she did have counted.92

According to Rubio, “Of [Montgomery’s] professors, Dr. Archibald MacMechan was the most influential,”93 in part because he “recognized Maud’s exceptional talent, and his praise encouraged her immensely.”94 Though perhaps best remembered as an astute literary critic (an early advocate of Herman Melville and Virginia Woolf, for instance), MacMechan was also a noted essayist in his day.95 By the time Montgomery was MacMechan’s literature student in 1895–96, he had already been a regular contributor to The Week (1883–1896), a Toronto magazine which Gerald Lynch and David Rampton identify as “the most prestigious forum for the essay [in Canada] in the late nineteenth century,”96 with William Connor noting that “Of recurrent contributors to the Week, the one most consciously writing in the familiar essay tradition was Archibald MacMechan.”97 Janet E. Baker observes in her dissertation on MacMechan, “Even MacMechan’s opponent and harshest critic, J.D. Logan, conceded that MacMechan was, in the context of Canadian literature, ‘an unsurpassed writer of the light essay.’”98 And so, in her only year of university education, Montgomery was trained by Canada’s most eminent essayist.99 I wondered if Montgomery read Montaigne in his class?100

Although she preambles it as a ramble, most of Montgomery’s essay isn’t concerned with the act of “rambling” (at least not the pedestrian kind), but rather depicts Montgomery reflecting on the tombstone inscriptions she reads in Halifax’s “old St. Paul’s graveyard,” which she writes is “set in the heart of the busy town.”101 In fact, much of Montgomery’s “ramble” is imagining. The pairing which presented itself to me is Joseph Addison’s “[On Westminster Abbey,]” published in Addison and Steele’s wildly popular essay periodical The Spectator on 30 March 1711,102 in which Addison similarly “amus[es] [him]self” one afternoon “with the Tomb-stones and Inscriptions” in London’s Westminster Abbey, and likewise reflects on and imagines about them.103 (As a former Haligonian in my undergrad days, I can’t help but see Halifax as the London of the Maritimes: the largest urban centre in the area, whose long imperial history is epitomized by its old cemetery.104)

In “A Half-Hour in an Old Cemetery,” Montgomery admits, “there is a certain kind of pleasure in [rambling in a graveyard] for some minds and moods; and when the place in question is garbed in the glamor of history and ‘unhappy, far-off things’ the pleasure is increased.”105 Similarly, Addison writes, “When I am in a serious Humour, I very often walk by my self in Westminster Abbey; where the Gloominess of the Place, and the Use to which it is applied, with the Solemnity of the Building, and the Condition of the People who lye in it, are apt to fill the Mind with a kind of Melancholy, or rather Thoughtfulness, that is not disagreeable.”106 Both essayists cue the reader, not for a simple sketch of these individual burying places, but a tour of their minds; their purpose isn’t to visit the graves of departed loved ones, but to explore a historic monument, accessible and well-known to those in their respective cities.

Addison uses the essay as an occasion to contemplate how death is the great equalizer, imagining the bones of the dead buried beneath the crowded edifice “crumbled amongst one another, and blended together in the same common Mass,”107 noting that most of the tombstones “recorded nothing else of the buried Person, but that he was born upon one Day and died upon another: The whole History of his Life, being comprehended in those two Circumstances, that are common to all Mankind.”108 While Addison’s essay—which appeared in The Spectator on Good Friday—turns out to be a contemplation of the Christian resurrection “when we shall all of us be Contemporaries, and make our Appearance together,”109 an unexpected turn of thought appearing near the essay’s end, Montgomery’s essay is a more secular contemplation about “the dread of oblivion”110 and how we remember or reimagine the past (without any such unexpected turn), subjects that are common to essayists.

In perhaps her most reflective moment of the essay, Montgomery writes, “The tombstones vary little in design or sentiment, yet one and all voice two of the most deeply-rooted instincts of humanity—the hope of immortality and the dread of oblivion.”111 She keenly observes that “These monuments were erected to perpetuate the memory of men and women wholly forgotten a generation ago!”112 After reading one “condensed biography” on a tombstone, Montgomery observes, “There is scope for imagination here”—if you’ve read Anne you’ll recognize this phrase—and then turns to that very act of imagining.113

While Addison’s imagining is grounded in the present, “consider[ing] … what innumerable Multitudes of People lay confus’d together under the Pavement of that ancient Cathedral,”114 while simultaneously imagining a future event, Montgomery’s is a reimagining of the distant past. “But what is this?” she asks. “We pause by a plain little headstone, covered from top to bottom by lettering that is blurred and worn. The cemetery with its overarching trees and long aisles of shadows, fades from sight.”115 Even before telling us what the inscription says, she shows us her imagining from reading it: “We see the Halifax harbor of nearly a century agone. Out of the mist comes slowly a great frigate … . Behind her is another … . Surely Time’s finger has turned back his pages,” Montgomery writes, “and that is the Shannon sailing triumphant up the bay with the Chesapeake as her prize!”116 She then tells us that the “little monument is a memento of that famous sea duel. Two officers of the Shannon, a boyish middy of 18 and a man well past middle age, are buried here.”117 This tombstone does precisely what Montgomery identifies as its intent: to “perpetuate the memory” of those long dead, and, in her case, it serves as a catalyst for reimagining that past.

Though the kind of imagining Montgomery includes in her essay may seem at odds with a genre that is generally considered to be non-fiction, essays often include an essayist’s imaginings, and unproblematically do so, as long as the essayist clearly cues the reader. In fact, it’s part of the essay tradition. Charles Lamb’s “Dream Children” is almost entirely a reverie, which the reader only discovers in its final sentences. Interestingly, Baker notes that “for MacMechan, the essay functioned as a suitable vehicle for combining fact and imagination. The essay allowed him the free-play of the imagination … over a given topic. His ideal essay was of the kind written by Montaigne or Lamb … .”118 It’s left to the reader to wonder whether Montgomery’s use of imagination in this essay—which she then reimagines as Anne’s own experience before she attends university—was influenced by MacMechan himself, and, indirectly, Montaigne.

Montgomery concludes her essay by announcing, “And so our half-hour ramble ends”—both the physical walk through the cemetery as well as her ramble in thought—“as we pass out by the beautiful tribute to Nova Scotia’s dead heroes … out into the busy streets again, leaving behind those … old forgotten graves of men and women who lived and loved and joyed and suffered when the last century was young.”119 Perhaps only ironically does Montgomery claim that they are forgotten, as she has just immortalized them by reimagining them in her essay.120 While Montgomery’s imagining of the past doesn’t move her essay forward into an unexpected turn of thought in the way Addison’s imagining does in “[On Westminster Abby,]” her imagining still invites the reader to enter into her mind for an essayistic ramble. After all, as she writes, “there is a certain kind of pleasure” in a ramble, solemn though it may be. But this mood soon dissipates when I turn the page and find myself laughing out loud at “Cynthia’s” column “Around the Table.”

“Around the Table”

Discovering that “Around the Table” is a series of periodical essays was a happy accident, like finding a book in a used bookstore which appears only when you’re least looking for it. Previous to writing this essay, I already knew the newspaper column was fictional (Montgomery’s own experience in Halifax was quite different from “Cynthia’s”121), so I hadn’t considered looking for the essay in “Around the Table.” (Besides, by the time I began writing, the column hadn’t yet been republished in full, and I saw little point of making a trip to Library and Archives Canada to peruse a microfilm in search of a weekly column which—though I also knew there were some non-fictional elements in it—I’d already disqualified as being essayistic.) Rather, I picked up “Around the Table” for fun (published in full for the first time in A Name for Herself) after I thought this essay—the one you are currently reading—was complete. But I soon realized that despite the fictionality of “Around the Table,” Montgomery was drawing heavily upon the essay tradition, displaying its humour, intimacy, reflections, and meandering structure. This was around the time I started reading Spinner’s recent anthology Of Women and the Essay, which added a substantial piece that had been missing from my understanding of the genre.

Before Lefebvre published “Around the Table” in A Name for Herself, scholars tended to gloss over its fictitious nature,122 using the column instead “to illustrate the author’s views”—a tendency Good identifies is common when essays are studied.123 In doing so, scholars presented “Around the Table” as though it were non-fiction, downplaying or even collapsing the entities of Montgomery and Cynthia, while also missing the pleasure of reading “Around the Table” as a periodical essay series. Kevin McCabe frankly dismisses it as “not always up to Maud’s usual standards,”124 a puzzling judgement when I read such playful sentences by Montgomery as, “I believe that in the foregoing paragraphs I have narrowly escaped being serious. To redeem my reputation for frivolity, I must tell you about some of the new shoes.”125 (I wonder: when studying an essay under academic strain, does one lose the ability to laugh?)

When Lefebvre published “Around the Table,” he admits that he couldn’t say “whether the column was unambiguously presented to readers as fiction,”126 and—struggling to categorize it further than a “newspaper column”127—notes that “‘Around the Table’ is a bit of an anomaly, since it is not journalism per se (in the sense that ‘Cynthia’ rarely reports on local or world events) and does not appear as part of a separate ‘women’s page’ common to so many newspapers.”128 He gets closer when he opines that it “contains some of Montgomery’s most innovative work.”129 Even without a named genre, Faye Hammill also detects something more going on in “Around the Table” when she reviews A Name for Herself, proclaiming that the instalments of “Around the Table” are “enthralling,” that Cynthia writes “in a witty and often innovative style,” and that the book is “worth the cover price for these pieces alone.”130

Montgomery herself claims that “Around the Table” is a column of “giddy stuff,” and that “everything is fish that comes to Cynthia’s net—fun, fashions, fads, and fancies.”131 While Montgomery’s may seem like a flippant appraisal, Priestley claims that an essayist is “a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles”132 and that “periodical writing encourage[d] the essayist … to focus his attention upon little passing things that he might have disdained were he not writing for the next week’s paper.”133 Lefebvre notes that “it is fortunate that [Montgomery’s] ability to write the witty column did not depend on her mood,” quoting the journal entry in which Montgomery said of “her ‘sparkling’ column, ‘I can always write brilliantly when I’m in the dismals.’”134 This detachment is in fact a desired characteristic for essayists, as seen with Rubio’s perplexity as to how Montgomery could have written that “charming piece” about her books.

The column centres on Cynthia’s observations about and conversations with a cast of characters—Polly, Theodosia, Ted, and Aunt Janet—who all live together in a Halifax household. The name of the column itself, “Around the Table,” suggests it may be a series of periodical essays, hearkening back to previous ones.135 Even a cursory glance at the titles of the instalments suggests that “Around the Table” has Montaignesque essayistic potential: “[A Walk in the Park],” “[Retrospection and Resolutions],” “[Unlikeable People],” “[Seeing and Perceiving],” and “[The Great Art of Packing a Trunk],” to name a few.136 And while each instalment is perhaps a bit too disjointed to be called an essay proper, there are mini essays within them, with Cynthia travelling from one subject to another in a loose, associative manner, as an essay does. In a single instalment she goes from commenting on the weather, to recalling bumping into a friend who was “reading people’s characters by their walk” (“it’s simply gruesome to reflect how many methods there are of giving ourselves away!”),137 to experimenting with “scripture cake” (“a dismal failure”),138 to her and Polly quizzing an unobservant Ted on bridal attire of a missed wedding, and finally wrapping it all up with a joke.139 She even calls attention to this meandering in a metaliterary moment, common to essays, by writing, “I suppose the law of the association of ideas is remotely responsible for the story that has just popped into my head in connection with the foregoing paragraph.”140

Her topics also align with those used by essayists. She begins one section by announcing, “Some day I’m going to write a treatise on the virtues of laziness. I like lazy people. They rest me.”141 Essayists are infamous for assuming contrarian positions (such as William Hazlitt in “On the Pleasures of Hating”), and the subject of laziness was common—even key—in conceptualizing themselves as essayists, the subject beginning with Montaigne, who wrote “Of Idleness.”142 Lopate notes that “personal essayists frequently represent themselves as loafers or retirees, inactive and tangential to the marketplace.”143 And while “Cynthia” herself does not fit this stereotype, as she overtly draws attention to herself writing her column, she still proceeds to write an albeit mini, but still several paragraphs long, “treatise on the virtues of laziness,” in which she claims, “There is wisdom in laziness—up to a certain degree.”144 Montgomery invokes the essay tradition, even while writing from a fictional perspective. But as others have pointed out, it’s not purely fiction.

Written in thirty-five instalments from 1901 to 1902 when Montgomery was working for the Halifax Daily Echo, “Around the Table” is told from a first-person point of view under the name “Cynthia,” in which Montgomery seemingly—and seamlessly—blends her own observations with a character biographically divergent from herself. More than a pseudonym for Montgomery, Cynthia, I soon realized, was a constructed fictional persona of a “periodical essayist.” Priestley observes that the periodical

gave [the essayist] a certain confidence and freedom he would not otherwise have had. When a man is writing regularly in one place for one set of readers (and nearly all the essayists were regular contributors to the Press, appearing in the same periodical at regular intervals), he tends to lose a certain stiffness, formality, self-consciousness, that would inevitably make its appearance if he were writing a whole book at once. He comes to feel that he is among friends and can afford, as it were, to let himself go, and the secret of writing a good essay is to let oneself go.145

When I read “Around the Table” in full for the first time, I likewise found a Montgomery who had “let [her]self go.” “What is the moral of this?” she asks at the end of one instalment. “Oh, there isn’t any.”146 “Here’s your laugh,” she writes in another. “I saw it in a newspaper the other day so it must be true.”147 But Priestley’s repeated male pronoun is telling.

Montgomery doesn’t disguise her narrator’s gender in “Around the Table” to fit into a long literary line of male essayists; rather, she reminds the reader of the female gender often. (This is in stark contrast with the androgynous “L.M. Montgomery” which she eventually settled on as her professional pen name, as Lefebvre discusses in his afterword to A Name for Herself.) “Myself, I think postscripts were invented to get people into trouble, and for no other purpose whatever. Being a woman,” she writes, “I always put postscripts on my letters, and I suppose I shall go on in the same old abandoned way to the end, albeit I know it is a bad, bad practice.”148 There’s no mistaking that this column is represented as being written by a woman—clearly signed by “Cynthia,” with an image header of several women talking around a table,149 and the first paragraph of the first instalment beginning, “This is the time of year when a woman starts to get or make a new hat. Now comes one of our chances for pitying the men. They never have the fun in selecting new hats that we have … .”150 Before reading Spinner’s book (which I began after “Around the Table”), I wondered: was Montgomery doing something revolutionary in writing a column that read like a series of periodical essays—like those by the great male essayists—but was by a pseudonymous woman writer?

I all but stumbled upon this paragraph in Spinner’s introduction:

Two eighteenth-century periodical essay conventions—an invented authorial persona and the blurring of fact and fiction—continued to characterize the essay well into the nineteenth century. … [Fe]w of the readily named male essayists of the nineteenth century relied on personae or pseudonyms for their works. In contrast, a greater percentage of women writers hung on to these fictive identities in order to maintain their artistic and personal integrity—that is, to protect their visions as writers and their reputations as women.151

Spinner claims that “what made the woman essayist possible in the eighteenth century has much to do with the periodical essay’s embrace of fiction (via personae and invented anecdotes and observations) as a means of conveying its message,”152 which is precisely what Montgomery does. “Even if many nineteenth-century women essayists”—Montgomery was writing at the turn of the twentieth—“were compelled to employ conventions of the eighteenth-century periodical essay long after male writers had abandoned them, these conventions still served them well.”153 If Montgomery’s “Around the Table” is read as a series of periodical essays—and if her contemporary audience recognized it as such by having read other periodical essays—it matters little whether it was overtly presented as fact or fiction, because her readers would have understood that the first-person narrator was a fabricated persona of the periodical essayist.

Spinner writes that “women periodical essayists … adapt[ed] the genre to their own project—even if such changes were so subtle as to barely distinguish women’s writings from men’s. One such move was Haywood’s invention of an all-female club of contributors to The Female Spectator.”154 Prior to Eliza Haywood, these clubs had been predominantly male. Interestingly, the characters in Cynthia’s household—she, Polly, Theodosia, Ted, and Aunt Janet—are all women with the exception of Ted, and while none of them contributes directly to her column (though they indirectly supply the anecdotes which Cynthia then reports on), they do make several direct references to her column, and could, in a way, be considered her very own (almost all) female club. Polly says, “I can’t write absurdities for the papers as you do, but I have more gumption about everyday matters than you have, Cynthia,”155 and Theodosia, “Now, Cynthia, don’t you go and put this in the Echo next Week,”156 which of course, she does.

Lefebvre claims that “while much of the ‘action’ of the ‘Around the Table’ columns takes place within the home, it is only occasionally concerned with domestic issues of any kind, focusing instead on the idiosyncrasies of the characters who live in the home.”157 This reads to me like apologetics for finding a trace of the domestic at all. But with Cynthia’s everyday observations permeating each instalment—in which she embraces all sorts of topics, fashion being a big one—I see the domestic everywhere in “Around the Table.” “[W]omen, especially respectable women, rarely participated in coffeehouse life,” the eighteenth-century London coffeehouse scene in which their male counterparts sought much of their material.158 And so, “women periodical essayists thus turned to the one place where they already had access: their own domestic sphere,” explains Spinner. “On the one hand, it was fortunate that the periodical essay was already turned in that direction, giving women writers a ready entrance into the genre.”159 But the domestic in the essay does not stop there.

Lopate (not unproblematically) has claimed that, for one noted essayist, “only the idle person is able to practice seeing … . The essayist here aligns himself with what is traditionally considered a female perspective, in its appreciation of sentiment, dailiness, and the domestic.”160 Yet Lopate has also unequivocally declared that “There were no female Hazlitts and Lambs,”161 a notion that has largely gone unchallenged until Spinner’s anthology. And while Spinner notes that “One of the greatest ironies of a form so long assigned to the domain of men is that its writers are often portrayed in feminine terms,”162 it’s a perspective which women essayists eventually assume themselves. When “Around the Table” is situated in the essay tradition, it’s clear that what Lefebvre calls the “domestic,” rather than being a liability, is an established subject and perspective of both men and women essayists.

In a hilarious essay from The Female Spectator, republished in Of Women and the Essay, Eliza Haywood begins her essay “[Hoops]” by writing, “I believe … that if the ladies would retrench a yard or two of their extended hoops they now wear, they would be much less liable, not only to … inconveniences …, but also to many other embarrassments one frequently beholds them in when walking the streets,”163 and so continues the essay, a delightful “warning”164 about “the angular corners of such immense machines.”165

It reminds me of how Cynthia began her own column, writing wittily of women’s hats. Fashion is a topic she returns to often, especially a comical appraisal of it. “Let me tell you the things I saw Polly do with a hair-pin in just one half hour,” Cynthia writes:

She buttoned her boots and gloves with one; she cut the leaves of her magazines and opened her letters with it; having mislaid the key of her jewel box she picked the lock with a hair-pin; she fished up a stick-pin that had fallen into a crack in the floor; she picked the meats out of a lot of walnuts; she impaled marshmallows to toast over the gas; she trimmed her lamp wick; she straightened one out and propped up a straggly flower in her window garden with it; she took a cork out of a bottle with one, and she pegged down a loose cord in her sweet-pea pyramid with another.

And yet some people imagine that all a hair-pin is good for is to pin up hair!166

The humour in the everyday—and humour found in fashion, specifically—is beautifully embodied in this passage.

But along with being a comic appraisal of the many uses of the unassuming hairpin, this passage also serves as an apt metaphor for the wit and ingenuity required of a woman to take a traditionally male literary form and make it her own. The common hairpin—like the traditional essay—in the end, is still a hairpin—is still an essay … but look what it can do in the hands of a woman! And the passage silently points to yet another example of wit and ingenuity. Many women essayists, including Montgomery, produced their literary feats in the midst of balancing various (and often invisible) domestic responsibilities.167 (As a present-day example: I gave birth to my second daughter between writing major drafts of this essay, a manoeuvre which—in the history of women essayists—isn’t an anomaly.168)

Or, one can simply enjoy the humour in this passage without looking any deeper than that.

In either case, Montgomery’s focus on the “domestic,” often treated in a humorous way and laced throughout the instalments of “Around the Table,” aligns “Cynthia’s” newspaper column with that of the periodical essay, which though more popular in preceding centuries, was still appreciated in her day.

Now is “The Age of Nonfiction,” when Montgomery’s essays need not be puzzled over, but simply enjoyed. “[O]ne of the reasons feminist recovery projects may be so late in coming to the essay,” writes Spinner, “is that the essay itself has long occupied bottom-shelf status in the hierarchy of literature … . Thus, women who write essays endure a second layer of neglect by composing in a historically understudied and underappreciated form.”169 Simply by situating “Around the Table” in the tradition of women periodical essayists, one can read it in the same spirit with which it was written, and “let oneself go.” I admit, I had to do the same, at first puzzled why an essay series was fictional, while, simultaneously, I enjoyed it.

Conclusion

Essays written by women, which historically have been overlooked, are now coming into their own at the same time that “The Age of Nonfiction” is being ushered into academia, including Montgomery studies. Lefebvre has published Montgomery’s essays, I’ve identified some of them with essay pairings to help clarify them within the genre, and—now that you’ve been properly introduced—I hope that you, too, will enjoy reading Montgomery’s (and others’) essays, with the same pleasure that they’re meant to be read. “[T]he desire which impels us when we take [the essay] from the shelf is simply to receive pleasure,” as Woolf writes.170 Elsewhere Woolf claims, “Second-hand books are wild books, homeless books; they have come together in vast flocks of variegated feather, and have a charm which the domesticated volumes of the library lack. Besides, in this random miscellaneous company we may rub against some complete stranger”—she is referring here to a book, which may well be a volume of essays—“who will, with luck, turn into the best friend we have in the world.”171

I began this essay by recalling how I once saw Montaigne and Montgomery side by side on the literature shelf of a used bookstore, wondering if Montgomery had read the father of the essay. Now, after my discovery that “Around the Table” is a series of periodical essays, I wonder: did Montgomery read any of the literary mothers of the essay? Eliza Haywood’s The Female Spectator or Frances Brooke’s The Old Maid or the essays of Margaret Fuller or of “Fanny Fern” could all be read alongside “Around the Table.” Montgomery’s essays “A Half Hour in an Old Cemetery” and “My Favorite Bookshelf” could likewise be read within the context of women essayists—notably Agnes Repplier, who also wrote in the style of the genteel essayist. Restraint on time prevented me from diving into the periodical essays of these literary divas myself (especially as I read Spinner so late in this writing), but are leads which I hope some curious reader will follow.

Which also brings me to my own postscript about Montgomery’s four-part essay series, beginning with “Spring in the Woods,” which I likewise didn’t have time to examine in this essay. I did, however, find an essay pairing for it, and, as it’s a rather curious incident, I’ll relay it briefly.

One evening while in the stacks of a university library, performing research which ultimately wouldn’t make it into this essay, I found myself standing before the bookshelf of call numbers PS8363–8373 (Canadian essay collections and essay anthologies, if you didn’t know). With the full run of The Best Canadian Essays before me, I randomly opened the 2011 issue, only to discover “The Protocols of Used Bookstores” by David Mason, a bookstore proprietor who once inscribed the chapbook version of it to me in the days when I too worked at a used bookstore (I hadn’t considered it an essay before finding it in this anthology, though). Consisting of forty-four “rules and guidelines on how to navigate a used bookshop,” his essay was written, in part, “to help make your quest for a book simpler … .”172 “Have some idea of what you are looking for, if only vaguely,” urges Mason in rule #6. “… [The proprietor] wants to help you find the book you need. Even if you yourself don’t know yet what that book is.”173 Though I was admittedly among “the domesticated volumes of the library” and so not likely to find the “wild books” of which Woolf speaks, Mason’s approximate presence seems to have infused them with second-hand bookstore–like behaviour, as one unexpectedly leapt off the shelf at me.

It was a modest volume, dressed in blue cloth, serviceable but somewhat dated, slender and small, with faded gilt lettering on its spine—Some Canadian Essays—its entire essence throwing into relief the loud, glossy contemporary covers standing several inches taller than it, brazenly advertising themselves to be “best.” I reached for this unassuming oddity, only to discover an anthology of essays “strictly within the ‘personal’ classification,” as its editor noted on the first page of his 1932 preface. I scanned the table of contents, my eyes resting upon an essay by Catharine Parr Traill called “In the Canadian Woods—Autumn.” Flipping to it, I read: “Silently but surely the summer with all its wealth of flower has left us, though we still have a few of its latest blossoms lingering on into the ripened glory of the autumn days.”174 It could have been straight out of Montgomery’s own essay “The Woods in Autumn,” one in her four-part seasonal series: “There is a magic in that scent of dying fir,” Montgomery writes. “It gets into our blood like some rare, subtly-compounded wine, and thrills us with unutterable sweetnesses, as of recollections from some other, fairer life, lived in some happier star.”175 The subject matter, the style, and the use of the first-person plural were all parallel. An essay pairing had presented itself to me. (Indeed, it turns out that the pairing is even more fitting than I first thought, as each is a four-part series with the essayist walking in the woods, one essay for each season.176)

But perhaps more than that, it reminded me of just how important the packaging of an essay is for its interpretation. I wouldn’t have known to look in Traill’s Pearls and Pebbles where “The Canadian Woods” was previously published, as the book isn’t presented as a collection of essays, and even if I had come across it there, I mightn’t have conceptualized it as an essay if I hadn’t already been on the lookout for one. It took the editor—who’s also an essayist—to read, identify, and select the piece and present it as an essay to be included in Some Canadian Essays, where I found it.

It makes me wonder if there are more of Montgomery’s essays out there: might her journals and letters be read with an eye for identifying essays hidden within them? I wonder how many more could be found and collected, assembled by some reader. Wouldn’t it be delightful to walk into a used bookstore one day and see a slim book, perhaps the size of Some Canadian Essays, with an equally unassuming title—something like L.M. Montgomery: Essays for Herself—a little mountain tucked in between two mountains, leaping off the shelf.

About the Author: Heather Thomson is an essayist and independent scholar, with an M.F.A. in creative writing from Brigham Young University where she specialized in the essay, and an M.A. in English literature from the University of Ottawa where she wrote her thesis on Montgomery’s journals. You can find her at commonplacebookblog.com, writing about creative non-fiction, writing, and the pleasures of reading. She lives in Montreal with her family and her books.

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Emily Woster, for generously sharing your wealth of knowledge of Montgomery’s reading, and to both you and Kate Scarth for encouraging me to go further and reflect deeper, which has only improved my writing. Thanks for taking a chance on an independent scholar. And to the two anonymous peer-review readers, whose invaluable feedback ultimately led to the direction this essay eventually would take, thank you.

Banner image derived from Reading from H. Thomson's personal collection, 2020.

- 1 Michel Eyquem de Montaigne (1533–1592) published his essays in 1580 (books I and II) and 1588 (book III, with additions), with further editorial additions to his essays published posthumously in 1595. The Essais have subsequently been translated into English multiple times, beginning with John Florio’s translation in 1603, and six different translations into English in the twentieth century alone.

- 2 In the entry on Montaigne in Encyclopedia of the Essay, Richard M. Chadbourne acknowledges point-blank that Montaigne, “quite extraordinarily for the inventor of a literary form, remains its greatest exponent …” (570), an assessment widely shared by essayists. In his well-regarded Introduction to The Art of the Personal Essay, Phillip Lopate goes so far as to dub Montaigne the “patron saint of personal essayists” (xxiii). And while David Lazar and Patrick Madden acknowledge in their introduction to After Montaigne: Contemporary Essayists Cover the Essays, that “For 350 years, almost every essayist paid homage to the creator of the essay form” (1), they also admit that “New students in MFA and PhD programs calling themselves essayists arrive (and sometimes even leave) without having read a single essay by the writer to whom they are inextricably indebted,” a trend which they hope their new anthology will “modestly correct … and reassert Montaigne’s centrality” (2). So while the status of Montaigne’s essays may have temporarily downshifted in some minds, Lazar and Madden can still confidently claim, “So much that’s vital about the essay seems uncannily present, explicitly or in utero, in Montaigne” (2).

- 3 Epstein, “Personal” 11.

- 4 Incidentally, commonplace books have been identified as a forerunner of the essay. Lopate explains that “the Renaissance essay partly grew out of the custom of keeping ‘commonplace books,’ which were filled with favorite quotations. In England, Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy, a learned catch-all encrusted with citations and meditations, became a kind of mother-text inspiring the essay form” (xli).

- 5 Montaigne, quoted in Lopate, Introduction xxiii.

- 6 Lopate xxiii.

- 7 Werner, “Personal Essay” 655.

- 8 Donaldson, Introduction 2.

- 9 Lopate writes, “I have never seen a strong distinction drawn in print between the personal essay and the familiar essay; maybe they are identical twins, maybe close cousins. The difference, if there is any, is one of nuance, I suspect. The familiar essay values lightness of touch above all else; the personal essay, which need not be light, tends to put the writer’s ‘I’ or idiosyncratic angle more at center stage” (xxiv). And in her anthology of essays by historical women essayists, Jenny Spinner matter-of-factly observes, they “may be classified as either personal, informal, literary, or belletristic (choose your own label)” (Of Women 4).

- 10 Woolf, “Modern” 44.

- 11 Ozick, “She” 151.

- 12 Smith, “Writing.”

- 13 In “Toward a Collective Poetics of the Essay,” Carl H. Klaus notes “the most striking … consensus” among essayists is their tendency “… to define the essay by contrasting it with conventionalized and systematized forms of writing,” including scholarly discourse (xv), that “the formal essay does not seem to figure in the thinking of essayists,” (xxi) and that “most essayists probably do not recognize the formal essay, because it embodies the very antithesis of what they conceive an essay to be” (xxi-xxii).

- 14 Ned Stuckey-French identifies some of the “aliases behind which the essay has hid or been hidden,” including the feature, piece, column, editorial, op-ed, profile, and casual (“Queer”).

- 15 For example, an early collection of scholarly papers about Montgomery’s writing has “essay” in its title: Harvesting Thistles: The Textual Garden of L.M. Montgomery, Essays on Her Novels and Journals (1994).

- 16 Spinner 4. Spinner notes these and other types of inclusions in her own edited anthology. One noteworthy example is the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who wrote in the eighteenth century.

- 17 Spinner 4.

- 18 Hodgins, “Neglect” 116.

- 19 Priestley, Introduction 17.

- 20 Kuist, “Periodical Essay” 650. Some of the most well-known periodical essays include those appearing in Richard Steele and Joseph Addison’s Spectator (1711–12; 1714), Samuel Johnson’s Rambler (1750–52), as well as Charles Lamb’s “Essays of Elia” (1820) and William Hazlitt’s “Table-Talk” (1821–22). Essays have continued to appear in periodicals devoted to the genre and as stand-alone pieces in periodicals until the present day. Though series of periodical essays by women essayists have largely been omitted and erased in the history of the essay, women likewise enjoyed success in their day, many of them appearing in Spinner’s recent recovery anthology, including essays from the periodical serial The Female Spectator (1744–46) by Eliza Haywood, and The Old Maid (1755–56) by “Mary Singleton,” a pseudonym of Frances Brooke (the same who moved to Quebec and wrote what many consider to be the first Canadian novel, The History of Emily Montague), and other women periodical essayists like Margaret Fuller, Agnes Repplier, and the popular “Fanny Fern,” a pseudonym of Sara Payson Wilson.

- 21 Klaus notes that “Twentieth-century essayists often … distinguish[ed] between the personal orientation of the essay and the factual mode of the article” (xix), and that “they depicted the article as embodying a naively positivistic approach to knowledge, an approach out of touch with the problematic nature of things” (xx).

- 22 While some of Montgomery’s earlier non-fiction periodical pieces also display essayistic qualities—notably her three 1891 pieces, “The Wreck of the ‘Marco Polo,’” “A Wester Eden,” and “From Prince Albert to P.E. Island”—for their keen observations, humour, and the personal presence of the writer, they ultimately are closer to sketches. While this footnote is not (nor is this essay) the place to delineate the finer differences between the essay and the sketch, I will take a brief moment to quote how others have described the sketch, and the sketch’s relation to the essay in the Canadian scene. In their introduction to The Prose of Life: Sketches from Victorian Canada, Carole Gerson and Kathy Mezei explain that “As a genre, the sketch can be defined as an apparently personal anecdote or memoir which focusses on one particular place, person, or experience, and is usually intended for magazine publication. Colloquial in tone and informal in structure, it is related to the letter, itself a device allowing a writer to be personal” (2). In Encyclopedia of the Essay, William Connor notes that “a discussion of the essay in Canada is … essentially a discussion of the familiar essay” (“Canadian” 143) and that “there was often a good deal of overlap between familiar essays and sketches” (143). “More descriptive and episodic than the essay,” Gerson and Mezei claim, “… the sketch provided an appropriate medium for recording and shaping noteworthy Canadian experiences” (1–2), while Connor explained that the sketch “Tend[ed] more toward narration and description than most essays” (143), also true of Montgomery’s early non-fiction. An interesting possibility for further study of Montgomery’s sketches with essayistic tendencies would be to study them comparatively with other periodical non-fiction pieces in the Canadian scene, which likewise displayed a “good deal of overlap” between the essay and the sketch.

- 23 Some of Montgomery’s earliest non-fiction periodical pieces were republished in The Years before “Anne,” Francis Bolger’s 1974 book-length study of Montgomery’s early writing career; other pieces appeared as supplementary material to critical editions of Anne of Green Gables: Broadview (2004), Norton (2007), and Penguin (2017); several more were excerpted in The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album (1999), and a single issue excerpt from Montgomery’s “Around the Table” was included in Elizabeth Epperly’s Through Lover’s Lane: L.M. Montgomery’s Photography and Visual Imagination (2007).

- 24 Of note are the initial efforts of the compilers who identified several “Miscellaneous Pieces” in Lucy Maud Montgomery: A Preliminary Bibliography (1986).

- 25 While a substantial amount of these works contains Montgomery’s non-fiction, these are not overtly or exclusively non-fiction collections of Montgomery’s writing.

- 26 Lazar, “Nonfiction” Essay Daily.