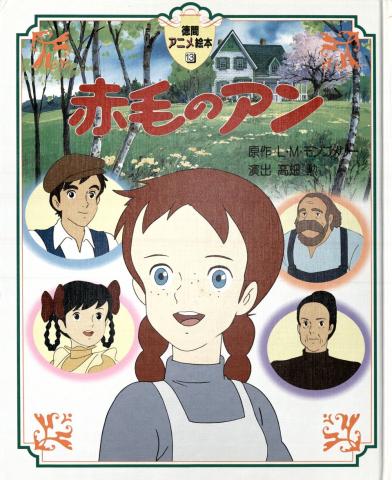

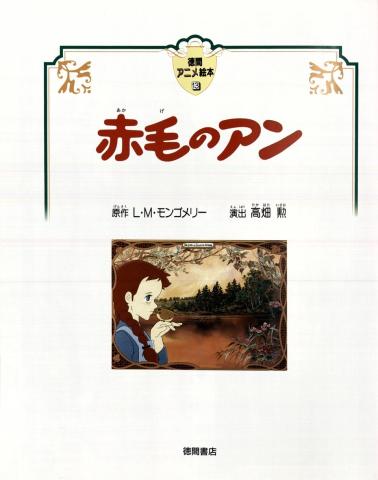

This paper explores the Japanese anime adaptation of L.M. Montgomery’s novel, titled Akage no Anne [Red-Haired Anne]. Akage no Anne successfully maintains the charm of the original narrative through the stylistic devices it possesses as an anime, therefore delivering an accurate and heartfelt visual reinterpretation of Montgomery’s imaginative vision.

Introduction

Akage no Anne [Red-Haired Anne]1 is a Japanese anime adaptation of Anne of Green Gables that was released in 1979. Part of the television staple World Masterpiece Theatre, it was written and directed by Isao Takahata, who went on to be one of the founders of Studio Ghibli alongside Hayao Miyazaki.2 Akage no Anne seems in many ways to be the most faithful existing adaptation of Montgomery’s novel, as it successfully captures the details and spirit of the book accurately and effectively. It also demonstrates that animation is effective as a form of storytelling as it fully utilizes the unique strengths animation possesses as a medium, highlighting that Akage no Anne deserves recognition as both a work of art and a respectful adaptation that captures the essence of Montgomery’s original vision.

This paper will begin with a brief discussion of the cultural influences shaping Takahata’s creative choices that place the anime mostly in the transposition category of adaptation. These choices reflect Anne of Green Gables’s immense popularity with its Japanese audience, this popularity probably being a significant reason for the decision that the anime would be a faithful portrayal of the book’s focal themes and values. This paper will then explore how the medium of animation is especially effective in translating Anne’s imagination and her coming-of-age character arc. To demonstrate the former, I will explore how the anime is able through the use of visual imagery to deliver organically dream or imagination sequences. In regard to the latter, I will examine the importance of pacing, as this is a key factor in the series’ effective portrayal of Montgomery’s work since it is able to produce an accurate adaptation throughout the span of fifty episodes, with each episode corresponding to a chapter.

Adapting to Animation

An essential element to Akage no Anne’s success as a faithful adaptation is that Anne of Green Gables is a beloved character in Japan and has been so ever since her first appearance there in 1952. According to Akiko Uchiyama, Japan developed an interest in western literature in the immediate post-war decades. As a result, the first translation by Hanako Muraoka was “an instant success.”3 Cecily Devereux goes further to suggest that Anne’s popularity transcends her Canadian origin, and that she has taken on a new identity as “a Japanese national figure.”4 Yoshiko Akamatsu observes that Anne has often been thought of as a role model by Japanese children due to her positive attitude. Akamatsu provides a comparison of Anne’s life with that of Japanese children: “In the 1950s and 1960s, the Japanese were struggling to live their impoverished lives in communities in which, like Avonlea, everyone knew everyone else.” Akamatsu sets a scene of a post-war Japan wherein children made a connection between their situation and that of Anne. War orphans, in particular, would receive comfort in the story of a girl who is able to overcome her cruel orphaned childhood and find love and acceptance while flourishing as a person. Akamatsu explains that Anne provided a narrative whereby the protagonist could freely express herself: “Since the Japanese value silence, children were not allowed to talk freely in the presence of adults. The talkative Anne became a new heroine symbolizing the democratic world after the war.”5 Margaret Atwood hypothesizes, “possibly Japanese women and girls found Anne encouraging … she triumphs without sacrificing her sense of herself: she will not tolerate insult, she defends herself, she even loses her temper and gets away with it. She breaks taboos.” Anne was seen not only as inspiring positive agency in her female readers but also as encompassing values important to Japanese society because, as Atwood further outlines, Anne possesses a strong work ethic towards her studies, respects her elders, and loves nature.6 Because Anne has these connections with Japanese society, there was a keen desire to keep the anime faithful to Muraoka’s Japanese translation of the novel.

Takahata shows the utmost dedication and care when adapting the source material, perhaps because his and Montgomery’s thematic interests overlap. One notable example is the narrative exploration of the coming-of-age genre. This theme would become important in his later works with Studio Ghibli, even in a two-hour film such as Only Yesterday, which was released in 1991. This film has constant flashbacks to the protagonist’s childhood, during which the line between these flashbacks and her present day blurs as the narrative progresses, since she continues to visualize the image of her younger self appearing before her. The ending of Only Yesterday presents her childhood self and her classmates cheering as she makes an important decision in her life, fully combining figments of her imagination with her reality in a single moment. Much time is spent on the protagonist reflecting on how she has developed as a person from the more talkative, often outspoken child she once was, just as Anne does. Takahata implements many stylistic devices in this film that were present in Akage no Anne, which serve to illustrate the gradual progression of Anne and her friends. An animated adaptation for Anne’s narrative is especially suitable because Montgomery had what Elizabeth Epperly refers to as a “visual imagination,” which stored “memory pictures” from clear recollections of her childhood.7 Anne from the anime stays true to Montgomery’s vision as she often looks back on childhood memories while commenting on how both her world and the people around her are changing.

Takahata effectively expands on Montgomery’s culturally adaptable themes. According to Colin Odell and Michelle Le Blanc, “In many ways, Takahata’s films are about imperfection and compromise; they affect their audience on an emotional level precisely because they mirror the truth.”8 This means that the raw, often emotional moments of humanity present in Montgomery’s novel remain intact because they complement Takahata’s area of expertise. Such moments include Marilla’s awareness of her developing maternal feelings toward Anne and Anne’s grief over Matthew’s death. Since hand-drawn animation requires much time and dedication to create, each scene, every movement, every line of dialogue, and every narrative point becomes a conscious choice. This makes it even more effective when the characters display the same subtle movements that live-action people do every day, such as subtle changes in facial expressions, or when the animation includes realistic sound effects for mundane actions like tea being poured into a cup. Despite their not being live-action, the characters feel real and organic.

Moreover, the visual medium also allows for the series to translate viscerally Montgomery’s more abstract ideas. For example, in the episode narrating the Avonlea girls’ Story Club, Anne’s story of Cordelia and Geraldine is depicted in animated stills in which the characters’ stylized designs resemble those from Victorian melodrama, separating them from the other characters’ simpler designs. This is one of the many instances that indicates the attention paid to preserving tiny details of the book. Therefore, Akage no Anne can be seen mostly as a transposition adaptation, wherein the narrative “is directly given on the screen, with the minimum of apparent interference.”9 Another notable example is Anne’s dress with puffed sleeves, which in the book and the anime is brown, unlike the 1985 miniseries directed by Kevin Sullivan, where it is blue. This is an instance when the anime has avoided making a deliberate change to the narrative. However, the anime also contains instances of being a commentary adaptation, as some events progress in a linear fashion as opposed to Anne’s retelling them in the book. When scenes are embellished from the original story, the additions feel natural, as they are consistent with the characters’ actions that reflect the themes of Montgomery’s novel; therefore, they can “fortify the values of its original on the printed page.”10 This is especially prevalent in the anime’s flashback episodes, which contain a self-contained plot that allows them to be framed around scenes from the previous episodes. Episode 25, for example, provides a setup wherein Diana is unwell, and Anne writes her a letter that reminisces on important moments of their friendship. The episode stays true to Anne’s character, as her imagination causes her to worry that Diana will die, which leads to her declaring how much their friendship means. At the end of the episode, Diana reveals that she has made a full recovery, and the anime is able to progress without any disruption to the original narrative.

Imaginative Visuals

Akage no Anne remains especially faithful to its source material through its full utilization of the animation medium. Animation has the potential for a more immersive experience than live-action films when portraying narratives that contain dream or imagination sequences, which are essential to this particular story. Animation is such an effective mode of storytelling because it allows the viewer to explore fully a character’s internal psyche, which is important for the character of Anne. Through the visuals, the viewer can witness the creations of her imagination and see them as clearly as she can.

According to Linda Hutcheon, through visual adaptions, “External appearances are made to mirror inner truths. In other words, visual and aural correlatives for interior events can be created.”11 For example, when in the anime Anne mentions something she imagines, it is followed by images of the scene her mind has created. What is more, this mirrors the storytelling of the entire anime as many instances of narration are accompanied by still images of the events being described.

In the first third of the anime, when Anne daydreams her imaginings almost overwhelm the reality of her situation. When her daydreams are interrupted, the images disappear in jump cuts, whereby the linear progressions from her dream and her present day are paced through abrupt transitions. This clearly shows how her imagination is so strong that it almost consumes her. However, with the terrible upbringing she has endured before the start of the main narrative and her arrival at Green Gables, it is understandable she wishes to escape from her reality; in this way, her imagination acts as a shield. One example that highlights this occurs in the first episode when she imagines sleeping in the cherry tree. The flowers shelter her like a shield, highlighting how her imagination has cushioned her from the harsh reality she has faced throughout her early childhood. This imagery, along with the jump cuts, underscores not only the strength of her imagination but also the difference between fantasy and her current reality. This is evident when she reflects on her past imaginary friend, Katie Maurice, whom she invented during a particularly harsh time in her life. As a result, the animated sequences serve to emphasize the importance of her imagination as a source of comfort. Sequences to show that Anne is daydreaming are represented by the appearance of beings she names “flower sprites,” which take the form of tiny fairies. They appear alongside flowers, emphasizing her connection to nature.

However, as the series progresses, the daydreams are not so pervasive. While her imagination remains a defining part of her character, it is no longer her only form of solace now that she has a family and friends who care about her. The anime self-consciously acknowledges this, as many episodes are dedicated to conversations during which Anne and her friends express awareness that they are growing up and that their lives are changing. Episode thirty-three, for example, contains a scene in which Diana tells Anne that they are much older and should be thinking about their futures rather than fairies, a favourite subject of their childhood fantasies. Indeed, Anne later demonstrates awareness of her development when, speaking with Matthew and Marilla in episode thirty-five, she says, “But if I have to start wearing longer dresses, I think I’ll have to start behaving accordingly, a bit more refined. And when one behaves in a refined fashion, one should perhaps stop believing in elves. That’s why I’ve promised myself I’ll believe in them for the last time this holiday.” She is attempting to act in a more adultlike manner by reflecting on the flower sprites her imagination used to conjure, while also providing an explanation for why they no longer appear in the anime. As a result, she acknowledges she does not need her imagination as much as she once did. This allows for the audience to be aware, as the characters are, of how much time has passed.

The anime continues to portray nature as an essential element of the narrative. This is often achieved through subtle imagery, such as images of the seasons to indicate the passing of time. The narrator draws attention to this through lines such as “Spring visits Green Gables again,” which are accompanied by painted stills of spring flowers and long shots of the vast meadows surrounding Green Gables, the latter conveying the wide open spaces of the countryside.

These images are similar to the beautiful landscapes that would become common in Studio Ghibli films and are effective in recreating the idyllic atmosphere that Montgomery provided. Nature continues to be prolific throughout the anime, as most of Anne’s imagined scenarios contain some form of nature, highlighting how it maintains a strong presence in her life, even when she grows out of imagining the flower sprites. An especially significant example occurs in the final episode when Anne imagines her future. The images she creates are surrounded by a border of leaves, implying that although she has grown up, she has not completely lost the spirit of hope and wonder that guided her through her childhood.

The anime’s visual portrayal allows for the narrative to fully take advantage of its organic pacing, which in turn reflects the aging process of Anne and her friends, with their physical features evolving into those of adults as the narrative progresses. This fits seamlessly with their more mature behaviour, indicating a realistic evolution. Even when there appears to be a time-skip to make a transition into their adult appearances, it is set up well, as in episode thirty-five when Anne says, “We should keep in mind that this’ll be the last summer holiday that I will spend as a child.” Following this is a sequence in episode thirty-six during which Anne and Diana find that Idlewild has been cut down. The juxtaposition of the present day and the flashback to when they played in Idlewild symbolizes the end of their childhood. The episode concludes with the narrator stating, “Suddenly Anne felt very grown up.” All of this is blatant foreshadowing for episode thirty-seven, when summer has ended and her physical transformation is complete.

The anime’s pacing over fifty twenty-four-minute episodes is part of what allows it to surpass previous film versions of the novel in terms of being a faithful adaptation.12 Many narrative points must be cut when a book is adapted to a short film or a miniseries such as Sullivan’s, which has a total running time of about three hours. While cuts are often unavoidable, they can disrupt the pacing of the source material, lessening the impact of important events, even “in a television series, [in which] there is more time available and therefore less compression of the adapted text is required.”13 Consequently due to its longer running time and prolonged release schedule compared to that of a film, the anime fully uses its potential to portray every chapter of the book in its entirety, as in the Akage no Anne anime in which each episode is devoted to the content of a corresponding chapter in the novel. It also allows for the addition of flashback episodes that flesh out what is only suggested in the original novel. In this instance, the flashbacks are well placed since the episodes aired weekly over the course of a year, and it was important to remind the audience how far the characters had come. While other television shows may include flashbacks to fill time, Akage no Anne incorporates them to provide the audience with a satisfying emotional payoff. An especially effective example takes place before Anne departs for Queen’s College: Marilla finds one of Anne’s old dresses and remembers the time Anne arrived at Green Gables. This invokes that despite their fractious beginnings, they have formed a strong familial bond as Marilla has come to view Anne as a daughter. The episode re-runs parts from the first episode when Marilla initially dismisses Anne as a mistake; following these scenes is a newly animated one when Marilla breaks down in tears at the sight of the dress, allowing the audience to experience the weight of her emotional journey.

Conclusion

Ultimately Akage no Anne understands what makes Montgomery’s story so beloved and fully embraces the task of handling its uplifting themes and coming-of-age narrative arc with the utmost care. The animated format serves to document accurately every significant aspect of Anne’s journey with beautiful visuals that recreate the idyllic scenery and fantastical daydreams. As a result, the anime serves to reinforce Anne of Green Gables’ status as a timeless classic by capturing and thus preserving Montgomery’s imaginative vision.

About the Author: Meriel Dhanowa is a Ph.D. student in Text/Image Studies at the University of Glasgow. She completed an M.Phil. at the University of Cambridge’s Centre for Research in Children’s Literature. Her research interests include Children’s Literature and Text/Image Studies.

- 1 The anime adaptation is usually spelled Akage no Anne in English. Japanese translations of the book title are often spelled Akage no An.

- 2 Odell and Le Blanc, Studio Ghibli 12.

- 3 Uchiyama, “Meeting the New Anne Shirley” 3.

- 4 Devereux, “‘Canadian Classic’” 25.

- 5 Akamatsu, “Japanese Readings” 207.

- 6 Atwood, “Reflection Piece” 222–3.

- 7 Epperly, Through Lover’s Lane 24.

- 8 Odell and LeBlanc 84–5.

- 9 Wagner, Novel 223.

- 10 Wagner 224.

- 11 Hutcheon, Theory of Adaptation 58.

- 12 For previous film versions, see https://lmmonline.org/screen/.

- 13 Hutcheon 47.

Works Cited:

Akamatsu, Yoshiko. “Japanese Readings of Anne of Green Gables.” Gammel and Epperly, pp. 201–12.

Atwood, Margaret. “Reflection Piece—Revisiting Anne.” Gammel and Epperly, pp. 222–6.

Devereux, Cecily. “‘Canadian Classic’ and ‘Commodity Export’: The Nationalism of ‘Our’ Anne of Green Gables.” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, vol. 36, no. 1, Spring 2001, pp. 11–49.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. Through Lover’s Lane: L.M. Montgomery’s Photography and Visual Imagination. U of Toronto P, 2007.

Gammel, Irene, and Elizabeth Epperly, editors. L.M Montgomery and Canadian Culture. U of Toronto P, 1999.

Hutcheon, Linda, with Siobhan O’Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge, 2013.

L.M. Montgomery Online. L.M. Montgomery Research Group, 2007–2014, https://lmmonline.org/screen/.

Odell, Colin, and Michelle Le Blanc. Studio Ghibli: The Films of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata. Kamera Books, 2019.

Uchiyama, Akiko. “Meeting the New Anne Shirley: Matsumoto Yūko’s Intimate Translation of Anne of Green Gables.” TTR: Translation, Terminology, Writing, vol. 26, no. 2013, pp. 153–75. Posted 22 June 2016, https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ttr/2013-v26-n1-ttr02584/1036953ar.

Wagner, Geoffrey. The Novel and the Cinema. Farleigh-Dickinson, 1975.