Sections

- What Is Visual Culture?

- Montgomery and Visual Culture: Objects, Artifacts, and Places

- Montgomery and "Virtual" Visuality

- “What Is It That You Learn When You Learn To See?”

- Subjectivity and Selfhood in Theory and Practice

- Emily of New Moon: Religious Publications and Fashion Sheets

- “Scraps and Patches”: Family Portraits

- Inspirational Writing Spaces: Fictional and Real

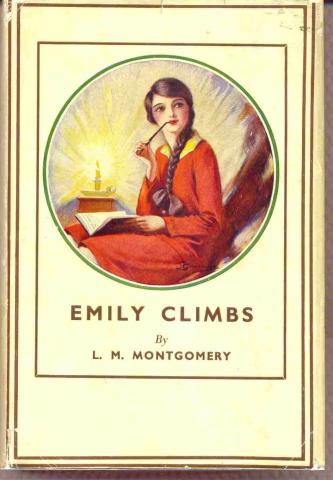

- Emily Climbs and Cultural Traces from Beyond PEI: Lord Byron, Queen Alexandra, Lady Giovanna

- Emily’s Quest, Elisabeth Bas, and Mona Lisa: Whose Story?

- From a “Smiling Girl” to The Smiling Girl: Emily Byrd-Starr Immortalised

- Shaping Character Through the Stories Visual Artifacts Tell

This paper examines L.M. Montgomery’s visualizing practices in developing Emily Byrd Starr as a woman and artist, focusing on the cultural “traces” (Gen Doy) of images, particularly portraits, and how Emily engages with—and ultimately resists—their encoded meanings and thus bequeaths a legacy to inspire others learning to look.

“You can do more with those eyes—that smile—than you can ever do with your pen.”1 With these words, Dean Priest attempts to relegate Emily Byrd Starr to “an inspiring female ‘face’ in a male artist’s repertoire.”2 Dean is not the only character in L.M. Montgomery’s Emily trilogy to consign women to an objectified subject position. For example, Father Cassidy facetiously claims to “keep [his mother] to look at,” and, until Emily recites a sample of her poetry, he seems to enjoy more what he sees than what he hears.3 Perhaps based on her success with Father Cassidy, Emily proceeds to plead her case with Lofty John by “summon[ing] all her wiles to her aid. She … looked up through her lashes at Lofty John, she smiled as slowly and seductively as she knew how—and Emily had considerable native knowledge of that sort.”4 Even Mr. Carpenter, a more promising mentor than Dean or Father Cassidy, remarks, “if you know how to dress yourself it won’t matter if you do like Mrs. Hemans.”5

Emily is learning the art of negotiation, and as Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright assert, “we negotiate the world through visual culture.”6 In “The Subject of Visual Culture,” Nicholas Mirzoeff defines the “visual subject” as “a person who is both constituted as an agent of sight … and as the effect of a series of categories of visual subjectivity”; therefore, “a new mantra of visual subjectivity” is “I am seen and I see that I am seen,” which has “provoked wide-ranging forms of resistance that were nonetheless, as Michel Foucault has argued, predicted by the operations of power.”7

Viewing Emily’s maturation through the lens of “a feminist, relational model of ethics” (as Mary Jeanette Moran has done for Anne),8 we can see Emily negotiating her visibility as a woman and writer as she discovers how her own narratives—past, present, and future—reflect, challenge, or subvert those of other women who are positioned as visual subjects. Although she ultimately attaches herself to a portrait painter whose reputation rests on pictures that she perceives to be a violation of the privacy of her innermost soul, Emily transcends these subject positions and becomes a creator in her own right as she unframes her sense of self and discovers her identity as, in Kenneth Gergen’s terminology, an “unbounded being,” whereby “what we call thinking, experience, memory, and creativity are actions in relationship.”9 One way that Emily does so is by interrogating and/or empathizing with women from an eclectic gallery of images: martyrs in illustrated missionary publications; bodiless ball dresses in contemporary fashion sheets; gloomy pictures of departed relatives; photographs of her mother; Aunt Ruth’s chromo of Queen Alexandra; engravings of portraits of Lady Giovanna, Elisabeth Bas, and the Mona Lisa; a miniature of Dean’s mother; and the sketches, illustrations, and paintings of Teddy Kent, who becomes renowned as an artist for his depictions of lovely women.

What Is Visual Culture?

For the past two decades, Montgomery scholarship has become increasingly rooted in the area of cultural studies, what Martin Lister and Liz Wells describe as “the study of the forms and practices of culture (not only its texts and artifacts), their relationships to social groups and the power relations between those groups as they are constructed and mediated by forms of culture,” whereby culture comprises “everyday symbolic and expressive practices, both those that take place as we live … and ‘textual practices’ in the sense that some kind of material artifact or representation, image, performance, display, space, writing or narrative is produced.”10 A branch of cultural studies is visual culture, which has been described variously as “a research area and a curricular initiative that regards the visual image as the focal point in the processes through which meaning is made in a cultural context” (Dikovitskaya), “how meaning is both made and transmitted in the visual world” (Howells and Negreiros), “the visual construction of the social, not just the social construction of vision” (Mitchell), “the means by which cultures visualize themselves in forms ranging from the imagination to the encounters between people and visualized media” (Mirzoeff), and “the shared practices of a group, community, or society through which meanings are made out of the visual, aural, and textual world or representations and the ways that looking practices are engaged in symbolic and communicative activities” (Sturken and Cartwright).11 Sturken and Cartwright’s definition of visual culture is most pertinent in its application to literature because then, as Jane Kromm and Susan Benforado Bakewell write, “visual culture can be gauged in terms of the objects it examines, the methods of interpretation or investigation it undertakes, and the subjects or viewers who engage with the objects.”12

Montgomery and Visual Culture: Objects, Artifacts, and Places

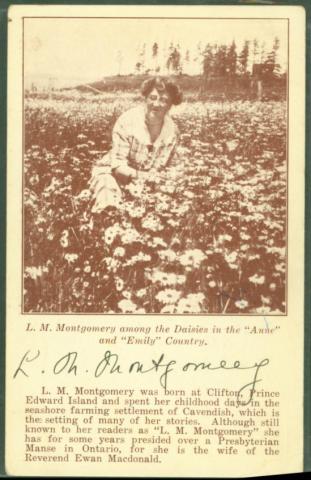

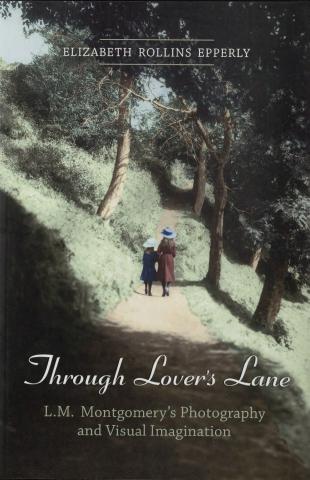

Having emerged and then deviated from traditional art history practices, which generally traced influences and movements of what was deemed “high culture,” visual culture often begins with an examination of objects or artifacts that have visual significance. Montgomery left a wide field to be tilled. First there are her photographs and scrapbooks, which Elizabeth Epperly examines in Through Lover’s Lane: L.M. Montgomery’s Photography and Visual Imagination and Imagining Anne: The Island Scrapbooks of L.M. Montgomery, respectively. There are, as well, the manuscripts of the journals and some of the novels, which can be considered as physical artifacts revealing much about Montgomery and her writing process; these have been discussed by (among others) Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston in their introductions and notes for the five volumes of The Selected Journals and two volumes of The Complete Journals (The PEI Years) and by Jen Rubio, editor of the five volumes of L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals (The Ontario Years), currently being published. Then there are the marginalia of the books in her library, now housed at the University of Guelph’s archives, explored by Emily Woster in “The Readings of a Writer,” her doctoral dissertation on Intertextuality and Life Writing: The Reading Autobiography of L.M. Montgomery, a chapter in L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys on the author’s reading practices during the Ontario years (“Old Years and Old Books”), and most recently, her keynote address at the LMMI 2018 conference on the databases she is building “to create a full and complete record of Montgomery’s reading life as we (can) know it.”13

Other visual artifacts that relate to Montgomery scholarship include book covers and illustrations, both of English and translated editions, which have been discussed by several Montgomery scholars, most notably Andrea McKenzie; picturebooks and graphic novels; and dramatic, musical, cinematic, and new media adaptations.14 How Montgomery’s characters are represented visually and cinematically is of concern for not only scholars but the general reading public as attested by the online furor that developed in 2013 over the buxom blonde “Amazon.com Anne” book cover or the heated commentary on CBC-Netflix’s adaptation, Anne with an E, and then later the “digital war,” crowdfunding, and strategic placement of five billboards in downtown Toronto and New York City’s Times Square that occurred in 2020 after Netflix’s cancellation of the series.15 The visuality of Montgomery’s works has in recent years inspired new media projects such as a digital literary tour, “The Inspiring World of L.M. Montgomery”; bookstagram sites, such as @trinna_writes; and fandom sites and vlogs, such as Green Gables Fables and the Finnish series Project Green Gables.

Of growing interest is the preservation of Montgomery memorabilia, housed in various archival collections (such as those at University of Guelph, Charlottetown’s Confederation Centre, and UPEI’s Robertson Library/L.M. Montgomery Institute) and heritage sites associated with Montgomery in both Prince Edward Island and Ontario. (Stay tuned for Carolyn Strom Collins’s “2020 Virtual Tour of L.M. Montgomery Sites on PEI,” with images from Bernadeta Milewski, to be posted later this week.) Also of interest are the commodification and commercialization that are sometimes the by-product of this preservation, originally critiqued by E. Holly Pike and Lorraine York, and more recently by (among others) Poushali Bhadury, Linda Rodenburg, and Sarah Conrad Gothie. Because Montgomery left photographs and descriptions of (as well as artifacts from) her domestic spaces, out of which she carved writing spaces, visual sources for her writing have been investigated in works such as Irene Gammel’s Looking for Anne: How Lucy Maud Montgomery Dreamed Up a Literary Classic and Margaret Steffler’s “Barriers and Portals: Writing through the Doors, Windows and Walls of the Leaskdale Manse.”

Montgomery and "Virtual" Visuality

Visual culture also can, as Kromm and Bakewell indicate, be more methodologically oriented, concerned more with “the methods of interpretation or investigation it undertakes” than “the objects it examines.”16 From the perspective of the literary scholar, Margaret Dikovitskaya writes, “there is a realm of what can be called ‘virtual’ visuality in literature implied by the text that contains images, inscriptions, and projections of space,” inviting an investigation of “descriptive literary texts where the projection of virtual spaces and places unfolds. Visual culture … refers to this world of internal visualization that appeals to imagination, memory, and fantasy.” Given that “the psychological notions of vision—interior vision, imagining, dreaming, remembering—are activated by both visual and literary means[,] … one begins to look at and actually examine the process of visualizing literary texts.”17 The most sustained work in Montgomery scholarship from a visual cultural perspective occurs in Epperly’s consideration of the visual imagination, culminating in the aforementioned Through Lover’s Lane and, more recently, in her article “Natural Bridge: L.M. Montgomery and the Architecture of Imaginative Landscapes.” By focusing on how Montgomery’s interest in the new technologies of photography reflects changing ways of looking and seeing at the end of the nineteenth and into the early decades of the twentieth century and by drawing upon recent work in the areas of visualization through cognitive studies, Through Lover’s Lane opens up further explorations of how visualization affects other cognitive and affective processes. Freud asserts that although the “recollection of adults … proceeds through different psychic material,” some visual, others not, “these differences vanish in dreams; all our dreams are preponderatingly visual. But this development is also found in the childhood memories; the latter are plastic and visual, even in those people whose later memory lacks the visual element.”18 “Montgomery’s habit was to look back,” Epperly writes.19 The nature of memories and dreams in Montgomery’s fiction and life writing as affected by and affecting the visual cultural context, in all its permutations, is a major and diverse area yet to be adequately investigated.

“What Is It That You Learn When You Learn To See?”

Dikovitskaya observes that “one of the main questions that visual culture addresses is: What is it that you learn when you learn to see?”20 Worded another way and applied to Montgomery, Epperly argues that Montgomery’s “artistry and her lasting power” are rooted in her “teach[ing] her readers/viewers to see what is there and what is not there; that is, she teaches her readers to see story and metaphor in images.” Epperly concludes that Montgomery’s fiction creates an “afterimage” (the title of the final chapter of Through Lover’s Lane) whereby “metaphor offers a continuing dialogue between two different states —what is present before the eye and what is suggested beyond it … Throughout her career, Montgomery developed a kind of shorthand with shapes, colours, and favourite expressions to invite readers to join her journey into, through, and beyond the arched, sunlit curves of her metaphoric Lover’s Lane.”21 The application of recent research in cognitive responses to visual elements within literature is another of the many areas of investigation that Epperly’s work generates. Empathy as triggered by visual elements, for example, is of growing interest in literary studies generally—a writer’s empathy with their subject matter through visual imagination and Dikovitskaya’s “‘virtual’ visuality” within a text that has the potential to evoke empathy from readers as they become a character—in this case, Emily—while immersed in reading.22

Subjectivity and Selfhood in Theory and Practice

This illustrated essay draws on these various areas of visual culture: physical artifacts (biographical and fictionally inscribed), ways of seeing and not seeing (and the politics of being seen and not seen), and the potential effect and affect on readers of different ways of seeing and not seeing, being seen and not seen. It does so within the theoretical framework of another topic that has interested scholars within the area of visual culture studies: subjectivity. In Picturing the Self: Changing Views of the Subject in Visual Culture, Gen Doy, a British artist, curator, academic, and writer, argues: “There are various ways in which subjectivity and selfhood relate to visual images. Images may represent people, and thus show us a version of the exterior appearance of the self, either individual, in a social group or as a member of a class. Portraits, for example, carry out this function as one their raisons d’être.”23 The portraits with which Montgomery’s Emily Byrd Starr engages, including portraits of herself, shape her as a woman and artist throughout the Emily trilogy. “Secondly,” Doy continues, “the ways in which the artwork is made are often read as expressions and traces of the individual subjectivity of the maker.”24 Thus not only the “traces” of Montgomery’s visualizing practices in Emily as an emerging writer but also the cultural “traces” of the portrait painters alluded to and/or portrayed in the three novels are of significance. “Additionally,” Doy concludes, “we need to consider the viewing subject, his/her positioning and the way in which the visual image or artwork may address a particular spectator. Meanings are not simply encoded into the image by its maker, but arise from the encounter of individuals or groups of viewers with the work.”25 What this illustrated essay demonstrates then is that by engaging with—and ultimately resisting—the encoded meanings and stories of portraits to which she is exposed, Emily bequeaths a legacy to inspire others learning to look.

Emily of New Moon: Religious Publications and Fashion Sheets

Emily’s initiation into the legacy of pictorial art—Ellen Greene’s illustrated book of Old Testament scenes with a “squat little apple-tree” flanked by the rigid figures of Adam and Eve and a bewhiskered God in a nightgown, and missionary magazines with pictures of starving victims of the Indian famine—shows Emily, from a young age, resisting the intended affect and effect of these images as she adapts these visual artifacts to her own world.26 She personalizes the Tree of Knowledge scene by applying the names “Adam” and “Eve” to two spruce trees in her own world; she rejects Ellen Greene’s version of an alienating male God outright; and the famine illustrations serve the same function as the illustration of a white ball dress that she has cut from a fashion sheet and pinned to her bedroom wall—an opportunity for self-dramatization.27

Dikovitskaya makes the point that “visual culture is the field in which social differences manifest themselves most dramatically … Clothing is particularly important here—fashion, the way people display themselves, presentation, bearing, and performance.”28 Montgomery drew upon her own practice of clipping fashion pictures and pasting them into her scrapbooks. Epperly remarks that every image in Montgomery's scrapbooks “is laden with memory and meaning,” including the fashion plates, which “suggest Montgomery analysing ‘woman’ and her place in the world.”29 These fashion plates also anticipate later fragmented images of the female body to which Emily will be exposed. Although all the fashion plates included in Montgomery’s scrapbooks have full bodies, the bodies, and especially the heads, seem totally disconnected from the garments being displayed.30 Given that Emily already feels that she is “scraps and patches” of Murray and Byrd and Starr and Shipley and Burnley from her high forehead to her dainty ankle, she readily projects her own visage onto the fragmented images, whether a faceless famine victim or headless “queen of beauty,” as she begins to negotiate her sense of being and belonging.31

“Scraps and Patches”: Family Portraits

When Emily arrives at New Moon, Aunt Elizabeth burns the image of the ball gown, so Emily turns instead to the material that the New Moon books shelves provide: missionary books with images of heathen chieftains who, when Christianized, cut off their hair.32 Emily’s sympathy for their sacrifice anticipates her defiance of having her own hair cut and her discovering the power of “the Murray look,” a reversal of her earlier engagement with the images of martyrs and queens of beauty because she has “an uncanny feeling of wearing somebody else’s face instead of her own.”33 This look, associated with Grandfather Murray, is not one to which she ever becomes reconciled; nevertheless, there are other ancestors to whom she is introduced, all those family members who have contributed to the “scraps and patches” that are Emily. Despite the walls of the tomb-like parlour being hung with pictures of cross, gloomy ancestors and the frightening few hours she spends locked in the spare room when Grandfather Murray’s “grim frown” provokes her escape, the lives of these ancestors give Emily a sense of belonging to New Moon, the “old cradle of her family”: she creates her own pictures of “Great-grandmother rubbing up her candlesticks and making cheeses; Great-aunt Miriam stealing about looking for her lost treasure; homesick Great-great-aunt Elizabeth stalking about in her bonnet … her own mother dreaming of Father—they all seemed as real to her as if she had known them in life.”34

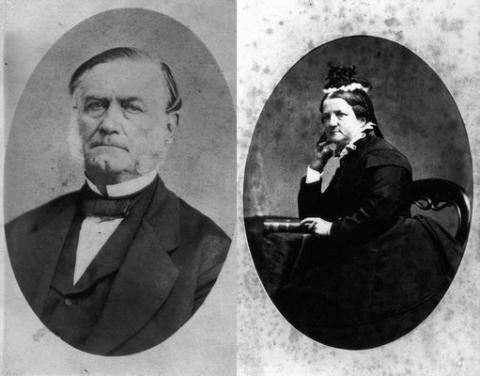

Right: Grandmother (Anne Murray) Montgomery (circa 1870s). L.M. Montgomery Collection, Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph Library, XZ1 MS A097020.

Please contact University of Guelph Library (libaspc@uoguelph.ca) regarding any planned print or electronic republication of these images.

Why does Emily believe in the existence of some ancestors but not that of Uncle Dutton, even when confronted with “his picture on the crêpe-draped easel” in Aunt Ruth’s parlour?35 One explanation is suggested by Geoffrey Batchen, whose theories about remembrance and photography are equally applicable to the images that Emily interrogates, whether daguerreotype, crayon enlargement, or oil painting. Discussing critics who “have argued that photography and memory do not mix, that one even precludes the other,” Batchen cites Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida —“Not only is the Photograph never, in essence, a memory … but it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter-memory”—and then interpolates: “Barthes based his claim on the presumed capacity of the photograph to replace the immediate, physically embracing experience of involuntary memory (the sort of emotional responses often stirred by smells and sounds) with frozen illustrations set in the past; photography, Barthes implies, replaces the unpredictable thrill of memory with the dull certainties of history … The challenge, then, is to make photography the visual equivalent of smell and taste,” something felt as well as seen.36

This Emily succeeds in doing by lifting her ancestors—whether captured on canvas or the silver-coated plate of the daguerreotype—from their gilt frames and off their easels and transporting them from “The Book of Yesterday” (the title of Chapter 7 of Emily of New Moon) into the Book of Today; feeling their joys and pains, she empathizes with them and becomes a medium to transmit their stories. A difference between the portrait and the photograph, Emily understands, can be the elusive “something” suggesting the subject’s life stories and requiring a human, not simply mechanical, medium.37 In the hands of the true artist, however, the photograph becomes a “memory picture” resonating with implicit stories.38 For Emily, as for Montgomery herself, storytelling provides “a bulwark against the erasures of death and time” by keeping alive the “absent presence” of those who have died.39 As she was planning, writing, and revising the Emily trilogy, Montgomery was recopying her early journals and rearranging the accompanying photographs and thus struggling to understand from the child’s, adolescent’s, and adult’s perspectives how her stories fit into her familial memories.40 By engaging with these visual artifacts, both Montgomery and Emily experience what Batchen calls “the act of remembering” that necessitates “the positioning of oneself … [and] establishing oneself within a social and historical network of relationships”; in so doing, “individual identity is posited not as fixed and autonomous but as dynamic and collective, as a continual process of becoming.”41

One scrap missing in Emily’s familial memories is a sense of her mother as a young girl before she eloped with Douglas Starr. Emily remembers her mother “just a little—here and there—like lovely bits of dreams.”42 A dominant memory Emily has of her dying father is their conversation about her mother, whom, he says, Emily does not resemble other than when she smiles. It is not until Emily returns from her visit to Wyther Grange “no longer wholly the child” that she not only enters her mother’s room for the first time but is given this room as her own, “one of those little household ‘epochs’ that make a keener impression on the memory and imagination than perhaps their real importance warrants.”43 In Emily’s “room of her own,” where all the scraps of furniture coalesce, she truly belongs because she feels “deliciously near to her mother.”44 Most important is the picture “of her mother hanging over the mantel—a large daguerreotype taken when she was a little girl … This picture, in her bedroom, of the golden-haired, rose-cheeked girl, was all her own.”45 Appropriately, Emily’s room has a mirror in which she can see her whole body without a distorted reflection, and appropriately, the “look out” this room grants is “through the gap in the trees where the Yesterday Road runs.”46 This picture of her mother is the final patch Emily needs for her own sense of being so she can broaden beyond her immediate family and, as her mother before her, extend her reach by negotiating relationships outside the boundaries of Blair Water to begin her journey on the Tomorrow Road.

Inspirational Writing Spaces: Fictional and Real

Right: Parlour of Leaskdale Manse (circa 1918). L.M. Montgomery Collection, Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph Library, XZ1 MS A097046.

Please contact University of Guelph Library (libaspc@uoguelph.ca) regarding any planned print or electronic republication of this image.

Emily’s New Moon room reflects two of Montgomery’s own writing spaces as Montgomery made the transition from Prince Edward Island, where the Emily series is set, to Ontario, where the Emily series was conceived and written. First is the “den” in her Macneill grandparents’ Cavendish home, which Gammel describes as “a museum in which Maud archived her memories. It was a place where time seemed to stand still.”47 This space thus resembles the village of Blair Water, which, near the end of the trilogy, is as Teddy remarks “quite unchanged … a place where time seems to stand still,” an observation anticipated earlier in the description of New Moon itself where “the carved ornament on the sideboard still cast the same queer shadow of an Ethiopian silhouette on exactly the same place on the wall where [Emily] had noticed it” seven years previously.48 In contrast to these frozen and fixed sites, Margaret Steffler describes how in Montgomery’s Leaskdale home, “the photos and pictures transform the walls into edges to be transcended rather than barriers to be overcome, so the walls, like the windows, allow both spatial and temporal transcendence of the restrictions imposed by both the literal and metaphorical ‘markers’ that delineate the Presbyterian manse.”49 As Emily takes her first steps along the Tomorrow Road, she too transforms her room into what Diana Fuss refers to as a “theater of composition” by introducing artifacts from beyond Blair Water that animate her writing space and determine the kind of writer she becomes; as Fuss writes generally of such “physical staging” for writers, “these material props, and the architectural spaces they define, are weighted with personal significance, inscribed in equal measure by private fantasy and cultural memory.”50 In the broader “arena of visual culture,” Irit Rogoff suggests, “we need to understand how we actively interact with images from all arenas to remake the world in the shape of our fantasies and desires or to narrate the stories which we carry within us.”51

Although Emily may appear to take her first steps along the Tomorrow Road on her trip to Wyther Grange that results in her being given this room of her own, these experiences simply mark further interrogation of the cultural “traces” of the Yesterday Road, beginning with her drive to Priest Pond and Old Kelly’s warning that Emily should marry young because “the less mischief ye’ll be after working with them come-hither eyes.”52 Great-Aunt Nancy Priest immediately assesses Emily in terms of “dead-and-gone noses and eyes and foreheads” that are “fitted on her,” but Emily shows “spunk” in standing up to her aunt: “I don’t like to be told I look like other people. I look just like myself.”53 During Emily’s stay at Wyther Grange, Great-Aunt Nancy attempts to initiate Emily into a faded, insalubrious world that objectifies and commodifies female beauty as a useful tool to ensnare men. With “Mary Shipley’s ankle” and the Murrays’ “keep-your-distance eyes,” but with her own lashes that can be “quite as effective as come-hither eyes,” Emily shows great potential to succeed in Great-Aunt Nancy’s yesterday world.54 Wyther Grange is crammed to the rafters with both Murray and Priest heirlooms and portraits; however, the gazing ball and the more recently acquired purloined painting by Teddy of a smiling Emily, which Great-aunt Nancy refuses to return because she predicts that it will someday be of value, “the early effort of a famous artist”55) will have the greatest significance for Emily’s emerging sense of being as woman and artist.

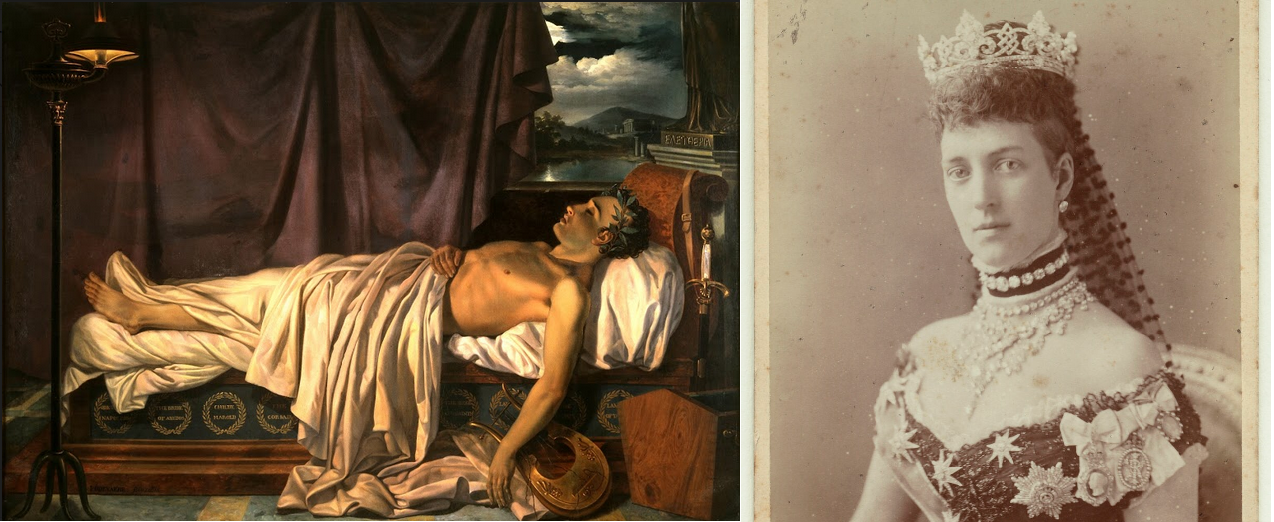

Emily Climbs and Cultural Traces from Beyond PEI: Lord Byron, Queen Alexandra, Lady Giovanna

In Shrewsbury, Emily takes great strides along the Today Road as evidenced by her response to three portraits that expose her to a visual cultural heritage from beyond Prince Edward Island through glimpses into other worlds and eras that outreach and outdate any Murray or Priest tradition. These come at an opportune time in Emily’s development. As she notes, somewhat facetiously, “one can do a great deal with appropriate smiles. I must study the subject carefully. The friendly smile—the scornful smile—the detached smile—the entreating smile—the common or garden grin.”56

Right: Queen Alexandra, albumen cabinet card by Alexander Bassano (1881). National Portrait Gallery, London.

In the hideously appointed, soulless kitchen chamber of Aunt Ruth’s ugly house, Emily keeps company with portraits of the dying Byron57 and of Queen Alexandra, consort to King Edward VII who came to the throne when Victoria died in 1901.58 The presence of the first portrait is totally inexplicable in a house owned by Aunt Ruth, who obviously does not know that “looking at Byron” was considered “as dangerous to young girls as reading his poetry”; perhaps there is a problematic connection between her customary fixation on slyness and hidden intentions and the expressionless death mask and the drapery covering Byron’s deformed right foot, which Byron always insisted any portraits conceal.59 That Emily is learning to read the unseen as well as the seen—an essential component of “visual culture [which] entails a meditation on blindness, the invisible, the unseen, the unseeable, and the overlooked”60—is also suggested by the numerous references to Queen Alexandra’s jewellery, especially the “dog collar” that unnerves Emily.61 Alexandra set the fashion for decades with her signature necklace encrusted with pearls and diamonds, purportedly to hide a small scar on her neck. To offset “Lord Byron’s funereal expression,” which Emily regards “an insult to her happiness,” and to “forget Queen Alexandra’s jewelry,” she introduces landscape sketches of New Moon that Teddy has drawn and an engraving of a desert scene from Dean, its “lure and mystery” becoming a portal “into a great, vast world of freedom and dream.”62 Emily now does most of her writing beside the Fern Pool, which reflects her own image rather than providing opportunities to experiment with the smiles and look through the eyes of others.63

The third portrait invites neither escape nor narcissism but interrogation and discovery. This is the gift that Dean gives Emily “to counteract Lord Byron” and which Aunt Ruth “doubts the propriety of having … in the same room with the jewelled chromo of Queen Alexandra”: “a framed copy of the ‘Portrait of Giovanna Degli Albizzi, wife of Lorenzo Tornabuoni Ghirlanjo’—a Lady of the Quatro Cento” by Domenico Ghirlandaio.64 Emily enjoys this portrait because of the subject’s “open, unshadowed brow, with the indefinable air over it all of saintliness and remoteness and fate—for the Lady Giovanna died young.”65 Emily concludes that Lady Giovanna may have been somewhat vain “in spite of her saintliness” and then articulates a most telling observation about her: “I am always wishing that she would turn her head and let me see her full face.”66 Emily empathises with Lady Giovanna, who has come down through the annals of history as one-quarter—the top left quarter—of the woman she must have been. Emily intuits, as visual culture theorist Patricia Simons articulates, that this profile portrait is “a fragmentary statement” characteristic of the “display culture” of the late fifteenth century and exemplifies the “anatomizing” of the female body, which is “scattered into separate areas such as neck, eyes, skin, mouth and hair.”67 Furthermore, because the portrait was painted posthumously, it acts as “a memory image that fills the void of her [in this case, Lady Giovanna’s] absence.”68

Paola Tinagli interprets Ghirlandaio’s painting not as a study of the self but as a dynastic, commemorative portrait “to remind viewers of Giovanna’s place within the family” with reference to the inscription in the background, which translates “Art, would that you could represent character [mores] and mind [animum]. There would be no more beautiful painting on earth”: “The conventions of the profile pose … were more suitable to convey the mores, the constructed behaviour, the virtuous conduct of these idealised women, together with the physical characteristics of a type of beauty, rather than the animus, the existence of a mind.”69 While intertextuality is a subversive strategy that Montgomery deploys throughout her novels—“She has validated female experience, given voice to female emotion, and helped remove women from imprisonment within silence and pain,” Rubio argues70 —only in the Emily books does the network of allusions include pictorial as well as literary references. Emily’s observations about Lady Giovanna are thus strategically placed shortly after Emily and Dean’s conversation about the slavery of love and Emily’s incipient uneasiness over Dean’s romantic overtures and patronizing attitude towards her art.71 When Emily leaves Shrewsbury, she writes that she is sorry to be leaving “poor dying Byron” but not Queen Alexandra and that Lady Giovanna will be travelling with her along the Today Road because she belongs in Emily’s New Moon room.72 Moreover, Emily includes Lady Giovanna in her list of what comprises her “real education,” who has taught her the most while at Shrewsbury.73

Emily’s Quest, Elisabeth Bas, and Mona Lisa: Whose Story?

Emily’s “real education” about the significance of this painting and of her immersion in visual culture comes several years later, after she is engaged to Dean and they are outfitting the Disappointed House from diverse “scraps and patches” of furnishings. In addition to Murray and Byrd and Starr and Shipley and Burnley, there is now Priest. The artifacts Dean introduces into the Disappointed House have stories attached to them, but they are stories foreign to Emily’s perception of the world. When Dean hangs a miniature of his beautiful mother over the mantel, Emily feels herself caught in a trap: she is a “sad lovely mother” who “had known fear; it looked out of her pictured eyes.”74 Other women whose portraits hang in this room also speak visually to Emily of “this subtle, secret fear that one could never put in words,” each in her own way.75 Emily thinks that Elisabeth Bas “could never have known the meaning of fear.”76 Dean introduces this painting into the room, hanging it by the fireplace, an “engraving from a portrait by Rembrandt.”77 (Since 1911, this painting has been attributed to Ferdinand Bol, not Rembrandt.78) Dean thinks her “a delightful old woman … did you ever see such a shrewd, humorous, complacent, slightly contemptuous old face?”79 Dean and Emily then discuss whether she had a less stern side, whether she ruled her husband, and whether she might be “a most delightful old maid,” all variations on Emily’s interpretations of Elisabeth Bas.80 Later, Emily sits under this portrait when she visits the Disappointed House trying to overcome her fear of tomorrow, and once her fear disappears, it is under the watchful eye of Elisabeth Bas that Emily has the vision of Teddy as she looks into Great-Aunt Nancy’s gazing ball.81

The other engravings are two that Emily contributes to the Disappointed House: the Lady Giovanna and the Mona Lisa, the latter probably another gift from Dean. Dean hangs them together in the corner between the windows, where he stages Emily’s future writing space. At this point, Emily is on a hiatus from writing so feels “indifferent” to the control that Dean is exerting over when, where, how, and what she will write.82 Revealingly, on Emily’s excursion to the Disappointed House to confront her fear, Lady Giovanna still fails to turn “her saintly profile to look squarely at [Emily]” and makes Emily feel that, were she able to verbalize her fear, the result would be “ridiculous.”83 Perhaps this is because “Lady Giovanna understands it all … dear little house! … never to be a home” for Emily as either wife or artist.84 Because Mona Lisa also seems to understand, she is well situated by Emily’s writing desk (in Dean’s imagined configuration of the room), recalling that, for Dean, “all other beauty is only a background for a beautiful woman.”85 In fact, he even proposes that “Mona Lisa will whisper … the ageless secret of her smile” for Emily to capture in a story.86 Dean interprets this smile in terms of a male story and male viewing community: comparing the difference between Elisabeth Bas’s smile and Mona Lisa’s, he concludes, “La Gioconda would be a more stimulating sweetheart.”87 This Mona Lisa—Dean’s version—mocks Emily’s fear of tomorrow both before and after she has rejected Dean. But there is one “smiling girl” that Dean cannot control. When Emily receives her inheritance from Great-Aunt Nancy—gazing ball, chessy-cat knocker, gold earrings—they are hung from filigreed Venetian lantern, front porch door, and Emily’s pointed ears, respectively; however, the remaining item from her inheritance—the purloined painting of Emily as a “smiling girl”—is put away in a box in the New Moon attic along with “old, foolish letters full of dreams and plans.”88

From a “Smiling Girl” to The Smiling Girl: Emily Byrd-Starr Immortalised

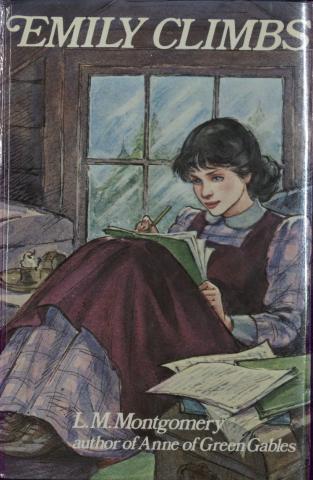

Dean would keep Emily enclosed in a gilded frame as if she were some iconic beauty from the past, made particularly clear when he dismisses her stories as “pretty cobwebs” and her literary ambitions as “childish dreams”: “I shall carry pictures of you wherever I go, Star … I shall see you sitting in your room by that old lookout window … wandering in the Yesterday Road.”89 Conversely, Teddy gives Emily the opportunity to travel with him on the Today Road into tomorrow. This journey begins with their childhood friendship. From a young age, the artist in Teddy responds to Emily’s “soft purple-gray eyes and a smile that [makes him] think of all sorts of wonderful things [he cannot] put into words,” a kind of otherworldly joy his art will immortalize.90 Teddy’s apprenticeship paintings, like Emily’s apprenticeship poems, feature local scenes, and he can wield his pencil, as Emily wields hers, to skewer those on whom they seek revenge for mistreatment,91 but the most influential pictures on Emily are the preliminary sketches for and ultimate production of The Smiling Girl that wins him international recognition.

Early in Emily Climbs, describing her long coveted, silver-blue shot-silk dress, Emily remarks, “Teddy says he will paint me in it and call it ‘The Ice Maiden,’” an allusion to Hans Christian Andersen’s story, a copy of which Teddy once loaned her.92 The ice maiden featured in Andersen’s fairy tale is a northern femme fatale, who tempts the young hero to his death, an ending Emily says she would revise. Despite “the Murray pride and the Starr reserve,” there is nothing of the femme fatale about Emily; however, she experiments with playing the femme fatale role when she has finally earned enough money from her writing to purchase her dream dress, a role that elicits the reproach from one ardent suitor “Ice-maiden! Chill vestal! Cold as your northern snows!”93 Much more significant for Emily’s emergence as artist and woman is Teddy’s promise to paint her as he observes her contemplating her Alpine Path, which even if she must travel solo, she will negotiate. They are walking “along the Tomorrow Road—which was almost a Today Road,” and as they “come to the end of the Tomorrow Road,” Emily “look[s] at the sunset sky—her eyes rapt, her face pale and seeking.” It is this image that Teddy, once he has the requisite skills, will immortalize: “I’ll paint you just as you’re looking now … and call it Joan of Arc—with a face all spirit—listening to her voices.”94 Epperly concludes that Teddy’s “androgynous image is particularly apt when we recognize the perdurable stereotype of femininity Dean tries to impose on Emily … [Teddy’s] admiration for Emily is, apparently, not merely a product of (male) romantic longing and fantasy, though it is pictorial and idealized. He sees Emily as Emily sees herself.”95

The fire of Emily’s “face all spirit,” and not the disdainful and ultimately destructive Ice Maiden, is the inspiration that transforms Teddy’s earliest watercolour painting of Emily “listening to something that [makes her] very happy” (the “Smiling Girl” that Great-Aunt Nancy appropriates for herself)96 through various permutations. Early in Teddy’s career, there are his signature images of Emily in magazine illustrations, which Emily finds so intrusive, especially those in which “only the eyes [a]re hers.”97 Ultimately, there is the painting that Ilse describes making “a tremendous sensation” when exhibited in Montreal and that has been accepted by the Paris Salon: “It’s you—Emily—it’s you. Just that old sketch he made of you years ago completed and glorified.”98 Ilse cites one critic’s prediction that “the smile on the girl’s face will become as famous as Mona Lisa’s,” the very smile she has so often observed, “especially when you were seeing that unseeable thing you used to call your flash. Teddy has caught the very soul of it—not a mocking, challenging smile like Mona Lisa’s—but a smile that seems to hint at some exquisitely wonderful secret you could tell if you liked—some whisper eternal—a secret that would make every one happy if they could only get you to tell it … What does it feel like, Emily, to realise yourself the inspiration of a genius?”99

Assessing how she feels about Teddy’s painting “her face—her soul—her secret vision,” Emily first feels “a certain small, futile anger” with him but then immediately has “an instantaneous vision” of the tales she has been weaving for her family “as a whole – a witty, sparkling rill of human comedy.”100 Just as one reviewer of Emily Climbs predicted that “Emily will take her place among the immortal children of literature,” Peggy, the heroine of The Moral of the Rose, is lauded as “one of the immortal girls of literature.”101 Emily has achieved, as Sturken and Cartwright discuss generally of someone who has learned to look, “a sense of … herself as an individual human subject, not only in … her own eyes and in the eyes of others but also in a world of natural and cultural places, things, and technologies that together make up the field of the gaze”; that is, she situates herself “in a field of meaning production (organized around looking practices) that involves recognition of [her]self as a member of that world of meaning.”102

In the opening pages of Emily’s Quest, the narrator, drawing “a portrait” of Emily at seventeen, remarks that “generations of lovely women” are behind Emily and concludes that she is “one of those vital creatures of whom, when they do die, we say it seems impossible that they can be dead.”103 Throughout the Emily trilogy, Emily has unframed her forefathers and foremothers, biological and cultural, and feeling their suffering and gladness, understanding and interpreting their behaviour and actions, she has infused their narratives with new life. There are times too when Emily sinks into despair and allows herself to become the passive subject rather than the active creator of the intersection of her narrative with the visual legacy inherited from her local and global ancestors. By the end of the trilogy, however, as both evocative subject of Teddy’s The Smiling Girl and celebrated author of The Moral of the Rose, symbiotic roles, Emily Byrd-Starr, soon to be Emily Byrd-Starr-Kent, is again being redefined. Her eyes and smile have not ensnared Teddy but rather inspired him to become an artist and husband worthy of her. Emily’s next step on the Tomorrow Road will move her yet further from her “foolish OLD SELF,” as she signs herself at fourteen, to an “unbounded being” with many more relationships to expand her identity and extend her influence beyond the boundaries of New Moon.104 At fourteen, Emily wonders “‘if, a hundred years from now, anybody will win a victory over anything because of something I left or did. It is an inspiring thought.”105 Alice Munro, Jane Urquhart, Margaret Laurence106—and thousands of other readers —concur.

Shaping Character Through the Stories Visual Artifacts Tell

Emily is the only Montgomery protagonist to develop into a literary artist, the only character to carve a writing space out of domestic space through the visual artifacts with which she interacts—artifacts that tell her their stories, which she then interpolates through her own way of perceiving them and her world. Other characters engage with visual artifacts, some prompting the kind of resistance observed in Emily as a young girl: the children’s distress in The Story Girl over the picture of God as a “cross old man” that they purchase from Jerry Cowan or Marigold’s hatred in Magic for Marigold of “Clementine with the lily,” the photograph of Marigold’s father’s first wife, to which Marigold’s mother is always being compared.107

Other visual artifacts provide comfort: Anne’s identification with the “lonely” girl in the blue dress in the “vivid chromo entitled, ‘Christ Blessing Little Children’”; Judy Plum’s picture of the white kittens, which she bequeaths to Pat and which is the sole object to survive the fire because Pat has sent it to Hilary; and Jane’s “fascination” with the newspaper image of a man, which she feels obliged to hide, not knowing that this image is of her father.108

Nor is Emily the only Montgomery character to be painted: in The Blue Castle, Valancy is painted by Allan Tierney, after Barney’s initial objection to having a picture of his wife “hung up in a salon for the mob to stare at,”109 and in “The Commonplace Woman” (The Blythe Are Quoted), Ursula’s hands are memorialized by Sir Lawrence Ainsley as hands capable not only of sewing but of murder. Then there are the characters who, because of superstition or “an exceedingly strict interpretation of the second commandment,” object to portraiture: Sarah Stanley’s and Sara Ray’s mothers, for example.110 All these—and others—invite critical attention for what they can reveal about how visual culture informs their lives and how visual artifacts work to shape character. In each case, as Gen Doy theorizes, “past, present and probably future selves can be viewed as complex and contradictory agents, making, and interacting with, material and social reality. Visual culture is part of that making, part of the understanding, and an important part of many subjectivities.”111

About the Author: Lesley Clement held teaching and administrative positions in Canadian postsecondary institutions, most recently at Lakehead-Orillia, before retiring in July 2018. She is the current Visiting Scholar at the L.M. Montgomery Institute, UPEI (2019–2021). She is on the editorial board of the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies and will assume the position of co-editor in July 2020, overseeing two special issues, one on the 2020 conference theme of “Montgomery and Vison,” another with Jean Mitchell on “Montgomery and Mental Health.” She is co-editor, with Rita Bode, of L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942 (MQUP, 2015). She has published articles on Montgomery in Studies in Canadian Literature (2011), L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Natures(s) (co-edited Bode and Mitchell, MQUP, 2018), and L.M. Montgomery and Gender (co-edited Holly Pike and Laura Robinson, MQUP, forthcoming).

Acknowledgements: Ideas in this paper have developed out of several previous presentations, beginning with a paper on “Emily’s Unframing of Self: Visual Culture, Empathy, and Subjectivity” at the LMMI Conference on “L.M. Montgomery and Cultural Memory” (June 2012), and then papers at NeMLA (March 2013), PAMLA (November 2013), and with Rita Bode at Leaskdale’s “Spirit of Canada Celebration” (October 2017). Thank you to Benjamin Lefebvre for suggesting some of the references cited in the final paragraph in an email (18 July 2013), to Rita Bode for helping me track down references during a time when library resources are limited, and to Kate Scarth for input and suggestions on the final version of this paper.

- 1 Montgomery, EQ 31.

- 2 Rubio, “Subverting the Trite” 31.

- 3 Montgomery, ENM 197, 201.

- 4 Montgomery, ENM 205.

- 5 Montgomery, EC 253.

- 6 Sturken and Cartwright, Practices of Looking 1.

- 7 Mirzoeff, “Subject of Visual Culture” 10.

- 8 Moran, “‘I’ll Never Be Angelically Good’” 54.

- 9 Gergen, Relational Being 61-63.

- 10 Lister and Wells, “Seeing Beyond Belief” 61.

- 11 Dikovitskaya, Visual Culture 1; Howells and Negreiros, Visual Culture 1; Mitchell, “Showing Seeing” 91; Mirzoeff, Introduction to Visual Culture 1; Sturken and Cartwright 3.

- 12 Kromm and Bakewell, History of Visual Culture 5.

- 13 The abstract of Woster’s keynote address, “L.M. Montgomery: The Reading of a Lifetime,” can be found here and the complete talk here

- 14 See McKenzie, “Patterns, Power, and Paradox” and “Writing in Pictures.” Some of these images can be accessed through the Confederation Centre’s "Picturing a Canadian Life: L.M. Montgomery’s Personal Scrapbooks and Books Covers" and the LMMI’s “Kindred Spaces: L.M. Montgomery Book Covers” and “Annes of the World.” Kate Scarth discusses some of the books in these collections and how they “evoke a sense of place” in “Exploring L.M. Montgomery’s Book Covers” (14 April 2020). To date, there are no bibliographies of picturebooks or graphic novels based on Montgomery’s writings and/or life, although as Kate Scarth and Emily Woster observe in their “Welcome” (2019) to the Journal of L.M. Montgomery Studies, “In the last year or two, there has been an upsurge in versions of Anne aimed at very young children with picture books featuring the red-haired heroine teaching lessons about places, the alphabet, numbers, colours, and friendship.” For a listing of film adaptations, see Lefebvre, “L.M. Montgomery: An Annotated Filmography” and here. For a sampling of critical articles on these film adaptations, see Lefebvre’s “Stand by Your Man” and “Road to Avonlea” and Brock-Servais and Prickett’s “From Bildungsroman to Romance to Saturday Morning.”

- 15 For the former, see Melanie Fishbane’s post in L.M. Montgomery Online on “The ‘Buxom Blonde’ Controversy of 2013” and Huffington Post’s “Anne of Green Gables Blond on Book Cover”; for the latter, see Sarah Larson’s 2017 New Yorker review, “How Not to Adapt ‘Anne of Green Gables,” and Leyland Cecco’s 2020 Guardian article on “Anne with an E Fans Wage Digital War with Netflix over Cancellation.”

- 16 Kromm and Bakewell 5.

- 17 Dikovitskaya 56.

- 18 Freud, Psychopathology of Everyday Life 63-64.

- 19 Epperly, Through Lover’s Lane 23.

- 20 Dikovitskaya 57.

- 21 Epperly, Through Lover’s Lane 178.

- 22 Dikovitskaya 56. For discussions of empathy and visualization, see, for examples, Clement, “Mobilizing the Power of the Unseen” and “The Empathic Poetic Sensibility: Discerning and Embodying Nature’s Secrets.”

- 23 Doy, Picturing the Self 7.

- 24 Doy 7.

- 25 Doy 7-8.

- 26 Montgomery, ENM 2.

- 27 Montgomery, ENM 23, 58, 49.

- 28 Dikovitskaya 245. For considerations of the visual cues of fashion in Montgomery’s fiction, see Clement, “Mobilizing the Power of the Unseen” 58-61; David and Wahl, “‘Matthew Insists on Puffed Sleeves’”; Gammel, Looking for Anne 178-81.

- 29 Epperly, Imagining Anne 8, 18.

- 30 For examples, see especially Epperly, Imagining Anne 77, 86, 87 (pages 63, 70, and 71 from the Blue Scrapbook) and 106, 107 (pages 8 and 9 from the Red Scrapbook). See also “A Fascination with Fashion” in the Confederation Centre’s “Picturing a Canadian Life.”

- 31 Montgomery, ENM 29, 49.

- 32 Montgomery, ENM 95, 99. This reflects the reading material available at the Macneill homestead (Montgomery, CJ 2 257-60).

- 33 Montgomery, ENM 106-07; cf. Montgomery, ENM 147.

- 34 Montgomery, ENM 97-98, 111, 89.

- 35 Montgomery, EC 223.

- 36 Batchen, Forget Me Not 15; Batchen quotes Barthes, Camera Lucida 91.

- 37 Montgomery, EC 30.

- 38 Epperly comments on Montgomery’s valuing of the storytelling potential of photography when Montgomery judged a Kodak competition in 1931 (Through Lover’s Lane 44; see Montgomery, CJ 7 178-79).

- 39 Rubio, Lucy Maud Montgomery 40.

- 40 Rubio notes that when Montgomery “was brooding up Emily in 1919-20, and writing the first draft in 1921-22, she was revisiting her childhood through a new lens, and she was once again reconfiguring her childhood in her journals” (Lucy Maud Montgomery 290); cf. Montgomery, CJ 4 179-83.

- 41 Batchen 97.

- 42 Montgomery, ENM 13.

- 43 Montgomery, ENM 282-83.

- 44 Montgomery, ENM 283, 285; italics in original.

- 45 Montgomery, ENM 285.

- 46 Montgomery, ENM 284, 286.

- 47 Gammel, Looking for Anne 142. Drawing upon Montgomery’s photographs and verbal portrayals, Gammel describes this den and its vista in detail (Looking for Anne 141-45).

- 48 Montgomery, EQ 168, 1.

- 49 Steffler, “Barriers and Portals” 69. Throughout her journals, Montgomery verbally and visually portrays various rooms, with their photographs, framed book covers, and pictures from magazines and calendars, which served her as writing spaces; however, only in her description of “Journey’s End,” her Toronto home, does she mention any “‘real’” pictures with the comment, “A blank wall is an unfriendly thing but the moment you hang a picture on it it becomes your friend” (Montgomery, SJ 5:14).

- 50 Fuss, Sense of an Interior 1-2.

- 51 Rogoff, “Studying Visual Culture” 16.

- 52 Montgomery, ENM 234.

- 53 Montgomery, ENM 240.

- 54 Montgomery, ENM 242.

- 55 Montgomery, ENM 277.

- 56 Montgomery, EC 101.

- 57 Although this reference could be to several portraits, the most likely is the oil on canvas painted by Joseph-Denis Odevaere. In her journals, Montgomery lists Byron as one of her favourite poets; however, she critiques his letters as having “a sense of unreality and posing” (Montgomery, CJ 3 154; CJ 4 254).

- 58 Teddy remarks that had the chromo “been Queen Victoria instead of Queen Alexandra” hanging at such a precarious angle, the adverse effects on Emily may have been even worse. Alexandra is a much more beautiful subject than Victoria: “Not even a chromo could make Queen Alexandra ugly or vulgar, but it came piteously near it” (Montgomery, EC 103, 96). A similar “luridly colored” chromo hung at the Macneill homestead, for which Montgomery recalls feeling extreme “distaste” (Montgomery, CJ 5 152). Montgomery expresses even greater distaste for the “abomination … a ‘chromo’ of the most aggravated description” at her Belmont rooming house and its potential to give its viewers nightmares and even drive them insane (Montgomery, CJ 1 342).

- 59 Jones, “Fantasy and Transfiguration” 109, 115-16.

- 60 Mitchell 90; cf. Sturken and Cartwright 6.

- 61 Montgomery, EC 102.

- 62 Montgomery, EC 132, 103.

- 63 Montgomery, EC 165.

- 64 Montgomery, EC 248-49.

- 65 Montgomery, EC 248.

- 66 Montgomery, EC 248-49.

- 67 Simons, “Women in Frames” 49, 41.

- 68 Cropper, “Beauty of Women” 188.

- 69 Tinagli, Women in Italian Renaissance Art 49-50, 79.

- 70 Rubio, “Subverting the Trite” 16; Rubio discusses literary allusions as the eighth of nine subversive strategies (“Subverting the Trite” 24-27).

- 71 Montgomery, EC 215-17, 258.

- 72 Montgomery, EC 324.

- 73 Montgomery, EC 250.

- 74 Montgomery, EQ 87.

- 75 Montgomery, EQ 87.

- 76 Montgomery, EQ 87.

- 77 Montgomery, EQ 78.

- 78 This painting of Elisabeth Bas is housed at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum, whose website previously (but no longer) noted the “heated discussion” that developed after 1911 when “the question arose whether the painting was indeed a genuine Rembrandt,” heated because of the attachment the public had for it, so much so that “the adoring public used to call this picture ‘Dear Old Woman.’”

- 79 Montgomery, EQ 78.

- 80 Montgomery, EQ 79.

- 81 Montgomery EQ 87-88.

- 82 Montgomery EQ 78.

- 83 Montgomery EQ 87.

- 84 Montgomery EQ 101.

- 85 Montgomery EQ 30.

- 86 Montgomery EQ 78.

- 87 Montgomery EQ 79.

- 88 Montgomery EQ 80.

- 89 Montgomery, EQ 30-31.

- 90 Montgomery, ENM 191.

- 91 Montgomery, ENM 125, 144, 164-65, 190-91.

- 92 Montgomery, EC 5; cf. Montgomery, ENM 158 and EQ 37-38.

- 93 Montgomery, EQ 177, 136.

- 94 Montgomery, EC 78-79. In her copy of George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan (1925), housed in the University of Guelph’s Archives, Montgomery glued magazine reproductions of George William Joy’s Le Repos de Jeanne (1895) and Jules Lenepveu’s Jeanne d’Arc au sacre de Charles VII (1874) as well as several magazine illustrations of the play in performance. For a discussion of this play's impact on Montgomery, see Clement, “Toronto’s Cultural Scene.”

- 95 Epperly, Fragrance of Sweet-Grass 171.

- 96 Montgomery, ENM 179-80, 226.

- 97 Montgomery, EQ 165; cf. Montgomery, EC 30-31 and EQ 65, 128, 223.

- 98 Montgomery, EQ 144.

- 99 Montgomery, EQ 144.

- 100 Montgomery, EQ 145.

- 101 Montgomery, CJ 7 21; Montgomery, EQ 179. Montgomery would have encountered the review of Emily Climbs on pages 252-53 of the Scrapbook of Book Reviews from Clipping Service, now housed in the University of Guelph’s archives. The quotation is from a review by Isabel Paterson, “A Rosebud Garden of Girls,” New York Herald Tribune Books (27 September 1925). It is reprinted in Lefebvre, The L.M. Montgomery Reader, Volume 3 260-61.

- 102 Sturken and Cartwright, Practices of Looking 103.

- 103 Montgomery, EQ 4-5.

- 104 Montgomery, EQ 161; Gergen 61-63.

- 105 Montgomery, EC 3; italics in original.

- 106 Waterston writes, “Alice Munro says [Emily of New Moon] was a watershed book for her. So does Jane Urquhart. Margaret Laurence said it recreated exactly how she felt as a budding artist” (Magic Island 228, note 80); cf. Rubio, “Subverting the Trite” 8-9.

- 107 Montgomery, SG 61-3; Montgomery, MM 43.

- 108 Montgomery, AGG 55-6; Montgomery, MP 270; Montgomery, JLH 34-36. In the Norton Critical Edition of Anne of Green Gables, Rubio and Waterston identify the “Christ Blessing the Little Children” chromolithograph as a picture created by Benjamin Haydon for a chapel in Liverpool, England (52, note 4).

- 109 Montgomery, BC 172-73, 216.

- 110 Montgomery, GR 184, 178.

- 111 Doy 188-89.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, 1981.

Batchen, Geoffrey. Forget Me Not: Photography & Remembrance. Princeton Architectural P, 2004.

Bhadury, Poushali. “Fictional Spaces, Contested Images: Anne’s ‘Authentic’ Afterlife.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 2, Summer 2011, pp. 214-37.

Bode, Rita, and Jean Mitchell, editors. L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Nature(s). McGill-Queen’s UP, 2018.

Bode, Rita, and Lesley D. Clement, editors. L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911-1942. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015.

Brock-Servais, Rhonda, and Matthew Prickett. “From Bildungsroman to Romance to Saturday Morning: Anne of Green Gables and Sullivan Entertainment’s Adaptations.” The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 34, no. 2, July 2010, pp. 214-27.

Clement, Lesley D. “The Empathic Poetic Sensibility: Discerning and Embodying Nature’s Secrets.” Bode and Mitchell, L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Nature(s), pp. 184-97.

---. “Mobilizing the Power of the Unseen: Imagining Self/Imagining Others in L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.” Studies in Canadian Literature / Études en littérature canadienne, vol. 36, no.1, 2011, pp. 51–68.

---. “Toronto’s Cultural Scene: Tonic or Toxin for a Sagged Soul?” Bode and Clement, L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, pp. 238-60.

Cropper, Elizabeth. “The Beauty of Women: Problems in the Rhetoric of Renaissance Portraiture.” Rewriting the Renaissance: The Discourses of Sexual Difference in Early Modern Europe, edited by Margaret W. Ferguson, Maureen Quilligan, and Nancy J. Vickers, U of Chicago P, 1986, pp. 175-90.

David, Alison Matthews, and Kimberly Wahl. “‘Matthew Insists on Puffed Sleeves’: Ambivalence towards Fashion in Anne of Green Gables.” Gammel and Lefebvre, Anne’s World, 35-49.

Dikovitskaya, Margaret. Visual Culture: The Study of the Visual after the Cultural Turn. MIT P, 2006.

Doy, Gen. Picturing the Self: Changing Views of the Subject in Visual Culture. I.B. Tauris, 2005.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. U of Toronto P, 1992.

---. Imagining Anne: The Island Scrapbooks of L.M. Montgomery. Penguin, 2008.

---. “Natural Bridge: L.M. Montgomery and the Architecture of Imaginative Landscapes.” Bode and Mitchell, L.M. Montgomery and the Matter of Nature(s), pp. 89-111.

---. Through Lover’s Lane: L.M. Montgomery’s Photography and Visual Imagination. U of Toronto P, 2007.

Freud, Sigmund. Psychopathology of Everyday Life. Translated A.A. Brill. Macmillan, 1914.

Fuss, Diana. The Sense of an Interior: Four Writers and the Rooms that Shaped Them. Routledge, 2004.

Gammel, Irene. Looking for Anne: How Lucy Maud Montgomery Dreamed Up a Literary Classic. Key Porter, 2008.

---, editor. Making Avonlea: L.M. Montgomery and Popular Culture. U of Toronto P, 2002.

----, and Benjamin Lefebvre, editors. Anne’s World: A New Century of Anne of Green Gables. U of Toronto P, 2010.

Gergen, Kenneth. Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community. Oxford UP, 2009.

Gothie, Sarah Conrad. “Playing ‘Anne’: Red Braids, Green Gables, and Literary Tourists on Prince Edward Island.” Tourist Studies, vol. 16, no. 4, December 2016, pp. 405–21.

Howells, Richard, and Joaquim Negreiros. Visual Culture. 2nd edition, revised and updated, Polity, 2012.

Jones, Christine Kenyon. “Fantasy and Transfiguration: Byron and his Portraits.” Byromania: Portraits of the Artist in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Culture, edited by Frances Wilson, Macmillan, 1999, pp. 109-36.

Kromm, Jane, and Susan Benforado Bakewell. A History of Visual Culture: Western Civilization from the 18th to the 21st Century. Berg, 2010.

Lefebvre, Benjamin. “L.M. Montgomery: An Annotated Filmography.” Canadian Children’s Literature / Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 99, Fall 2000, pp. 43-73.

---, editor. The L.M. Montgomery Reader. Volume Three: A Legacy in Review. U of Toronto P, 2015.

---. “Road to Avonlea: A Co-production of the Disney Corporation.” Gammel, Making Avonlea, pp. 174–85.

---. “Stand by Your Man: Adapting L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables.” Essays on Canadian Writing, vol. 76, Spring 2002, pp.149–69.

Lister, Martin, and Liz Wells. “Seeing Beyond Belief: Cultural Studies as an Approach to Analysing the Visual.” Handbook of Visual Analysis, edited by Theo van Leeuwen and Carey Jewitt, Sage Publications, 2001, pp. 61-91.

McKenzie, Andrea. “Patterns, Power, and Paradox: International Book Covers of Anne of Green Gables across a Century.” Textual Transformations in Children’s Literature: Adaptations, Translations, Reconsiderations, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, Routledge, 2013, pp. 127-53.

---. “Writing in Pictures: International Images of Emily.” Gammel, Making Avonlea, pp. 99-113.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. An Introduction to Visual Culture. 2nd edition, Routledge, 1999.

---. “The Subject of Visual Culture.” Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, pp. 3-23.

---, editor. The Visual Culture Reader. 2nd edition, Routledge, 2002.

Mitchell, W.J.T. “Showing Seeing: A Critique of Visual Culture.” Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, pp. 86-101.

Montgomery, L.M. Anne of Green Gables. 1908. Seal, 1983.

---. The Blue Castle. 1926. Seal, 1988.

---. The Blythes Are Quoted. Viking, 2009.

---. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889-1911. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 2012-13. 2 vols.

---. Emily Climbs. 1925. Seal, 1983.

---. Emily of New Moon. 1923. Seal, 1983.

---. Emily’s Quest. 1927. Seal, 1983.

---. The Golden Road. 1913. Seal, 1987.

---. Jane of Lantern Hill. 1937. Seal, 1988.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1911-33. Edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills Press, 2016-19. 5 vols.

---. Magic for Marigold. 1929. Seal, 1988.

---. Mistress Pat. 1935. Seal, 1988.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985-2004. 5 vols.

---. The Story Girl. 1910. Seal, 1987.

Moran, Mary Jeanette. “‘I’ll Never Be Angelically Good’: Feminist Narrative Ethics in Anne of Green Gables.” Gammel and Lefebvre, Anne’s World, pp. 50-64.

Pike, E. Holly. “Mass Marketing, Popular Culture, and the Canadian Celebrity Author.” Gammel, Making Avonlea, pp. 238–51.

Rodenburg, Linda. “Bala and The Blue Castle: The ‘Spirit of Muskoka’ and the Tourist Gaze.” Bode and Clement, L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, pp. 203-20.

Rogoff, Irit. “Studying Visual Culture.” Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader, pp. 14-26.

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Doubleday, 2008.

---. “Subverting the Trite: L.M. Montgomery’s ‘Room of her Own.’” Canadian Children’s Literature / Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 65, 1992, pp. 6-39.

---, and Elizabeth Waterston. A Norton Critical Edition: L.M. Montgomery, Anne of Green Gables. Norton, 2007.

Simons, Patricia. “Women in Frames: The Gaze, the Eye, the Profile in Renaissance Portraiture.” The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History, edited by Norma Broude and Mary D. Garrard, Westview P, 1992, pp. 39-57.

Steffler, Margaret. “Barriers and Portals: Writing through the Doors, Windows and Walls of the Leaskdale Manse.” CREArTA, vol. 5, 2005, pp. 63-75.

Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford UP, 2009.

Tinagli, Paola. Women in Italian Renaissance Art: Gender, Representation, Identity. Manchester UP, 1997.

Waterston, Elizabeth. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery. Oxford UP, 2008.

Woster, Emily S. Intertextuality and Life Writing: The Reading Autobiography of L.M. Montgomery. PhD Dissertation, Illinois State U, 2013.

---. “Old Years and Old Books: Montgomery’s Ontario Reading and Self-Fashioning.” Bode and Clement, L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys, pp. 151-65.

---. “The Readings of a Writer: The Literary Landscape Created by L.M. Montgomery’s Love of Literature.” CREArTA, vol. 5, 2005, pp. 209-22.

York, Lorraine. “‘I Knew I Would “Arrive” Some Day’: L.M. Montgomery and the Strategies of Literary Celebrity.” Canadian Children’s Literature / Littérature canadienne pour la jeunesse, vol. 113–14, Spring–Summer 2004, pp. 98–116.

---. Literary Celebrity in Canada. U of Toronto P, 2007.