Several years ago I appeared on Finnish TV as "the girl from PEI" among some of Finland’s L.M. Montgomery enthusiasts, writers, and scholars. Authors Annina Holmberg and Rauha S. Virtanen (often referred to as Finland’s Montgomery), journalist Suvi Ahola, and others asked me whether I married a “Teddy” or a “Dean.” I was confused because I had never thought of my partner as a particular prototype, let alone one modelled on Montgomery’s fictional men. Dumbfounded, I listened to them confess to their choices and explain how Montgomery’s Emily (“Emilia” in Finnish) had set them thinking about husbands, even driving them toward their own choices of partner. It was obvious that both Anne and Emily had been guiding lights for them from an early age, and Emily was the reason they too aspired to write.

That was the beginning of my relationship with these women, some of Finland’s leading writers and journalists, whose life works had opened my eyes to the impact Montgomery has had on her Finnish readers. Two of them, Suvi Ahola and Satu Koskimies, had collected stories from Montgomery readers and published a thick volume in 2005 called Uuden Kuun ja Vihervaaran tytöt: Lucy M. Montgomeryn Runotyttö- ja Anna-kirjat suomalaisten naislukijoiden suosikkeina [The Girls of New Moon and Green Gables: L.M. Montgomery’s Emily and Anne Books as Favourites Among Finnish Female Readers]. This book was published before several of them decided to make a pilgrimage to Prince Edward Island to share their insights and enthusiasm for Montgomery at the 2006 L.M. Montgomery Institute conference, “Storm and Dissonance.”

Ahola and Koskimies’s book is a strong affirmation of Montgomery’s popularity in Finland and how she impacted sixty-four women born between 1927 and 1990—including Finland’s leading playwrights, journalists, writers, as well as kindergarten teachers and librarians—who gave testimony of their encounters with Montgomery’s fictional characters. Finnish businesswoman Ulpu Aario’s story is one of the most touching as it describes her childhood years in Sweden during the Second World War. Evacuated from war-stricken Finland like many children of her generation, she later found solace in recalling how her fate was similar to Anne’s and even how some members of her Swedish foster family resembled Montgomery characters, like her Pappa corresponding to kind-hearted, soft-spoken Matthew Cuthbert.

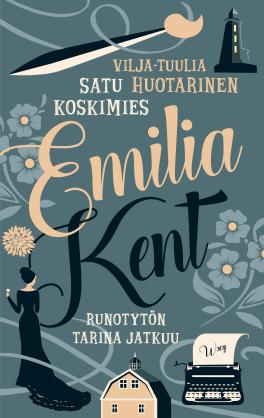

The collection clearly demonstrates that Montgomery lives on in the hearts and minds of Finnish women, particularly those in the middle-age-plus generation. In fact, Satu Koskimies, seventy-nine, and Vilja-Tuuli Huotarinen, forty-two, poets on opposite ends of the middle-age spectrum, were so inspired by Montgomery, and especially Emily, the aspiring poet, that they wrote a continuation to her story, Emilia Kent—Runotytön tarina jatkuu (2018).

Emilia Kent—Runotytön tarina jatkuu, translated as Emily Kent—The Girl Poet’s Story Continues, is a novel of twenty-eight chapters with vignettes enlarging on the themes of friendship, love, and writerly aspiration introduced in Montgomery’s three Emily books—Emily of New Moon, Emily Climbs, and Emily’s Quest.

In the opening chapter, Emilia receives a letter from New York, and the familiar handwriting signals to her, and hence to the Finnish reader of Montgomery, the identity of the sender. But the letter, revealed to be from her would-be literary patron Miss Royal, remains unattended to in the blue vase with the deep yellow flowers from Emilia’s childhood home, Uusi Kuu [New Moon], while Emilia and her new husband Teddy Kent get on with their lives as writer and painter, respectively.

One of the beauties of the Finnish language is that it allows long sentences for embedding extensive detail, preparing the reader to re-enter the original setting. Thus, the scene is set for the authors to take off with their story. One such example—“side by side on the surface of the oak china cabinet were the rings left by Emilia’s glass of milk from the time she spent studying in Shrewsbury and when aunt Ruth had remarked that Emilia may as well have the piece of furniture as her own”—indicates Koskimies and Huotarinen’s attention to details found in the original Emily stories.1

When reading this passage and others similar to it, I was able to build a bridge between the original Emily books and the Finnish counterpart Emilia.

A Finnish Reader of Emily, Then and Now

Kaarina Suvanto, a Finnish translator, was greatly influenced by Emilia as a child, as Suvanto too loved writing and aspired to be a writer. I met Kaarina and her best friend Riitta more than forty years ago when I came to Finland, and we recently discussed her response to Emilia.

When reading Emilia Kent—Runotytön tarina jatkuu, Suvanto, now in her early seventies, went back to her own feelings as a young wife. She recalled being delighted to get her own desk at that time in her life and later her own room where she translated films while mothering her three boys.

Having had an extensive career working in translating the Finnish language, Suvanto compared Koskimies and Huotarinen’s language to that found in Finnish classics for girls, particularly those by Anni Swan. In a telephone conversation Suvanto told me Emilia Kent reads like one of these older classics, citing in a follow-up email this description from the beginning of chapter two: “the leaves of birch trees look like they are gossiping together.”2 Then over the telephone Suvanto added, “I never understood why Emilia was interested in Dean Priest who was older and not very interesting,” so once again a Finnish woman takes up Emilia’s men!3

Problematizing Love and Marriage

Koskimies and Huotarinen play out numerous scenarios between Emilia, Dean, and Teddy focused on the balance between amorous and artistic pursuits. In one of their chapters, there is trouble in Blair Water, and subtle hints of jealousy are woven in with scenes of Emilia and Teddy’s married life. Emilia’s former fiancé, Dean, recently returned from one of his many world tours, appears on the doorstep of Autio Talo [Deserted House, that is, the old John house] while Teddy is away planning one of his collaborative exhibitions with fellow artist Norah Niles.

Emilia recalls how one snowy night years ago in this same house she exchanged glances with Teddy, and she “never really belonged to herself again.”4 This is the house Dean gave to his friends, Emilia and Teddy, as a wedding gift on the condition that he could occasionally overnight there, and here Teddy now sits reading his diary to Emilia. “You have been brief in details when it comes to me ... I thank you for that. But I can’t stop you from writing about your feelings.” Dean turned his gaze from his diary to Emilia, saying, “You are an amazing woman, Emilia. Fortunately you are married, otherwise I would propose to you again.”5 While at times a tinge of Harlequin romance emerges, in this continuation of the story romance is always bound up with artistic ambition. Dean’s and Emilia’s common passion for writing is reignited with Dean’s visits and Teddy’s collaboration with Norah, and Emilia’s snubbing of her husband’s flamboyant collaborator introduces another dimension of the erotic tension that emerges through their individual creative endeavours and the resulting collaboration with like-minded “kindred spirits.”

Another dilemma Koskimies and Huotarinen have Emilia face is whether to have a career or a family. Emilia is still living in a very traditional community in 1930s PEI when she challenges the status quo and eventually decides to postpone motherhood. Instead, she accepts the offer made in Miss Royal’s unattended letter in the blue vase: to attend a writers' conference in New York.

It is well known that Emily and Montgomery have much in common. Both were, for example, challenged by questions of love and marriage and creativity/writing. When it came to choosing a husband, ultimately, Emilia’s choice is between an amorous partner, Teddy, or one who epitomizes universal, agape love, Dean. In Emilia Kent, Dean’s unexpected visit and their shared passion for writing rekindle their love in a more erotically charged way than the love she shares with Teddy.

The morning after Dean’s surprise visit, Emily experiences a tumult of conflicting emotions under the same roof with these two men. Later in the day, in Teddy’s absence, Emilia expresses that Dean’s presence reawakens her feeling of kindredness towards him. She recalls how in her past under the moonlit night with Dean she felt like a wild cat. At the same time Emilia wonders whether Teddy ever recognized this devilishness in her. Dean and Teddy’s interaction over the breakfast table further draws out the differences in Emilia’s loves: Dean’s playfulness in introducing Norah Niles into the conversation and Teddy’s matter-of-fact denial that he has yet really got to know her further accentuate the two men’s differences. Even in her younger years, Emilia drifted between her friendships with Teddy and Dean. But that flexibility (or indecision) was part of the beauty of youthful friendship.

Interestingly, Montgomery herself had been tormented by feelings for two men, Herman Leard and Edwin Simpson. It was a surprise Christmas visit by Simpson in Lower Bedeque that prompted Montgomery to write in her journal: “There was I under the same roof with two men, one of whom I loved and could never marry, the other whom I had promised to marry but could never love!”6 Koskimies and Huotarinen took Emilia to this same situation to experience the tensions between true love and marriage.

In 1921 Montgomery admitted that she had been carrying “Emily” around in her head for the previous ten years, in other words, since the time she had married Ewan Macdonald in 1911.7 “Emily” and “The New Moon Series” emerged from Montgomery’s imaginative return to her years as a young woman and were now written up by a middle-aged woman coping not only with the memories of her early life in rural Prince Edward Island but also the increasing demands of being a mother of two young boys and the wife of a church minister struggling with mental illness in a new setting, Ontario.

P.K. Page in her afterword to Emily’s Quest sees Emily as an heiress of Montgomery’s “blue diamond,”8 a love that embraces all—friendship, passion, worship—and a further acknowledgement of Montgomery’s own failure to find true love and passion in her marriage to Ewan Macdonald. In this Finnish sequel we are reunited not only with Emilia but also the age-old questions of love, marriage, and artistic aspiration.

About the Author: Mary McDonald-Rissanen was born and raised in Summerside, Prince Edward Island. She did her undergraduate studies at UPEI, received an M.A. (TEFL) from University of Reading (UK), and Ph.D. from University of Tampere (Finland). She lives in Finland where she teaches English, lectures, and conducts research on language and literature. She is an active member of the Nordic Association of Canadian Studies. With a focus on women’s writing, she has presented at conferences throughout Europe. In 2014, she published In the Interval of the Wave: Prince Edward Island Women's Nineteenth- and Early Twentieth-Century Life Writing (McGill Queen's University Press).

- 1 Huotarinen and Koskimies, Emilia Kent 5. Quotations from this text are my own unpublished translations unless otherwise noted.

- 2 Suvanto, telephone conversation; Suvanto, personal email; Huotarinen and Koskimies, Emilia Kent 16. Suvanto’s quotation of Emilia Kent is her own translation.

- 3 Suvanto, telephone conversation.

- 4 Montgomery, EC 269.

- 5 Huotarinen and Koskimies 235.

- 6 Montgomery, CJ 1 (8 April 1898): 400.

- 7 Montgomery, CJ 4 (11 May 1921): 320.

- 8 Page, Afterword 239.

Works Cited:

Ahola, Suvi, and Satu Koskimies, editors. Uuden Kuun ja Vihervaaran tytöt: Lucy M. Montgomeryn Runotyttö- ja Anna-kirjat suomalaisten naislukijoiden suosikkeina [The Girls of New Moon and Green Gables: L.M. Montgomery’s Emily and Anne Books as Favourites Among Finnish Female Readers]. Tammi, 2005.

Huotarinen, Vilja-Tuulia, and Satu Koskimies. Emilia Kent—Runotytön tarina jatkuu. Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö, 2018.

Montgomery, L.M. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1889–1911. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 2012–13. 2 vols.

---. Emily Climbs. 1925. Seal Books, 1998.

---. Emily of New Moon. 1923. McClelland and Stewart, 1989.

---. Emily’s Quest. 1927. McClelland and Stewart, 1989.

Page, P.K. Afterword in Emily’s Quest, by L.M. Montgomery, 237–42. New Canadian Library. McClelland and Stewart, 1989, pp. 237–242.

Suvanto, Kaarina. Telephone conversation. 5 August 2020.

---. Personal email. 5 August 2020.