Using the lens of scholarship on the gaze and Jacques Lacan’s theories on the mirror stage, this essay examines how in L.M. Montgomery’s novel Kilmeny of the Orchard, Kilmeny Gordon’s position as titular character and protagonist and her potential—even capacity—to grow and change is undermined by Eric Marshall’s male gaze, which fixes her forever as a framed picture.

Kilmeny of the Orchard is ostensibly about a voiceless young woman whose violin music is her most poignant, although not only, outlet for expression and communication. Montgomery originally published this short novel as a serial, “Una of the Garden,” between 1906 and 1907. Her first publisher, L.C. Page, then persuaded her to expand and publish it in book form in 1910, shortly after the 1908–1909 releases of the first Anne books.1 She herself recognized how “very different” Kilmeny is from Anne of Green Gables and Anne of Avonlea, describing it in her journal as “a love story with a psychological interest … a rather doubtful experiment with a public who expects a certain style from an author.”2 While two later journal entries from the 1920s reflect a more positive perception of Kilmeny, most of Montgomery’s immediate reflections about the novel during its writing, revision, and publication throughout 1910 and early 1911 simply describe the authorial process or are ambiguous about how she came to feel about this “doubtful experiment.”3 Reviews were predictably mixed, reflecting the “contradictoriness” that amused Montgomery many years later as she reread critiques of her work.4 In one notable journal entry from 1 Sept. 1924, approximately fourteen years after Kilmeny’s initial publication, Montgomery records her son Stuart reading Kilmeny and being “very much absorbed in it. He runs to me every few minutes to read me some passage that has struck his fancy.” This observation suggests that the eight-, almost nine-year-old Stuart enjoyed the fairy-tale quality of the novel, a quality identified and discussed by Elizabeth Waterston in Magic Island and Mary Rubio in her biography, The Gift of Wings.5 His response, reflective of the response of other contemporary readers, suggests that Kilmeny had an appeal to audiences despite Montgomery’s reservations about it. Perhaps Montgomery’s discomfort is a result of how different Kilmeny is from so many of her other novels because, while those other novels have autonomous female characters whose growth is not for the most part determined by male influences, this novel, despite its title, is about the male protagonist, Eric Marshall, and his desire to attain a beautiful woman, even if he must create her himself. Therefore, Kilmeny Gordon’s position as titular character and protagonist and her potential—even capacity—to grow and change is undermined by the male gaze, which fixes her forever as a framed picture.

Scholarship on Kilmeny of the Orchard and the Gaze

The gaze that both exploits and erases Kilmeny from her titular role has been remarked by Montgomery scholars in their discussions of the novel. While both Waterston and Rubio note the hallmarks of a fairy tale, Elizabeth Epperly, in The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass, redirects the conversation, referring to the novel as a “formula romance” in which Eric is a “new knight errant” and Kilmeny “the best of the old-world stock.” In her analysis of Kilmeny as a formula romance taking “its pattern from old-fashioned chivalry,” Epperly focuses on the visual nature of the book, stating that Kilmeny is “really a picture drawn by Montgomery’s accommodating and flattering pen,” and that she “remains a beautiful picture” throughout the novel.6 Epperly’s references to both Kilmeny’s stasis and the pictorial quality of the novel suggest but do not elaborate the artist’s process in developing a painting and the fixed nature of a completed painting, the subject of which is always susceptible to the spectator’s gaze.

Scholarship on the gaze is often associated with film studies and the study of other visual arts such as painting or photography. Film critic and director Laura Mulvey’s seminal essay, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” identifies two major theories informing the male gaze that apply not only to film but also to Kilmeny of the Orchard: Sigmund Freud’s concept of scopophilia, in which a spectator views “other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze,” and Jacques Lacan’s theory of the mirror stage in infant development, during which a child first “recognises its own image in the mirror” and from that “crucial” point begins developing the idea of self. Mulvey connects these two apparently dissimilar ideas by demonstrating how spectators are located both “within the screen story” (as is Eric who becomes the primary spectator in Kilmeny) and “within the auditorium” or entirely outside of the “screen story” (as is the reader who is located outside of Montgomery’s novel).

But whether inside or outside of the frame, spectators of both types take pleasure in looking at an object (usually female) portrayed in the story. Mulvey explains, this pleasure in looking leads the spectators watching from outside the story to create an idealized image of themselves through watching the male spectator who is within the frame, and who has control over the female object in the story.7 Readers of Kilmeny are put in the unusual position—unusual for Montgomery, that is—of being forced to see through Eric’s perspective, first viewing Kilmeny as artwork and later watching Eric effect a scene with Kilmeny that is similar to Lacan’s mirror stage, thereby controlling her growth and development. For resistant modern readers, such positioning can generate discomfort over an exploitative male gaze diverting their own perspective and perhaps erasing their own stories, which Montgomery may have intuited in her own response to this novel being a “doubtful experiment.”

Much of the scholarship on the gaze in Montgomery’s work focuses on book-cover illustrations8 and film and television adaptations of her novels.9 But for Kilmeny of the Orchard—with its medieval romance elements, recurring references to visual artwork, and the narrative shift brought about by Eric’s introducing Kilmeny to a mirror—a more revealing approach is to focus on the effect of the male gaze on female characters. From the start, the readers’ view of Kilmeny is framed through Eric’s gaze. Eric admires Kilmeny upon seeing how beautiful she is and guides and shapes her from a childlike state into his ideal woman, an ideal based largely on the memory and a picture of Eric’s dead mother. Like the mythological Pygmalion, as narrated by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, Eric then falls in love with the woman he has created. However, the process of idealizing and “sculpting” her begins even before he first observes Kilmeny in the old orchard. Early in the novel, Eric and his friend David Baker discuss the physical appearance of the young women in Eric’s university graduating class, describing them as “made out of gold and roseleaves and dewdrops.” In contrast, Eric’s ideal look is “tall” and “dark” with “ropes of hair and a sort of crimson, velvety bloom.” This standard of beauty, although the details may differ, is reflected in the picture prominently hanging in the Marshall family home on a “dark wall between the windows” of Eric’s dead mother, whose “fine, strong, sweet face … was a testimony that she had been worthy of [her husband’s and son’s] love and reverence,” as Eric’s future wife will be.10 Because Eric’s image of his ideal woman derives from the framed picture of his mother, he consistently perceives Kilmeny as an objet d’art from the time he first sees her. Eventually, he provides her with a mirror, thus becoming instrumental in how she sees herself as a kind of framed picture, reflective of the image of Eric’s mother.

Eric as Spectator and Artist

When Eric first sees Kilmeny in the old Connors orchard, he stands and watches her, himself unseen, as if from the centre of Michel Foucault’s “panopticon,” a place or situation whereby the viewing subject is centrally located and “sees everything without ever being seen” while the viewed object “is totally seen, without ever seeing.”11 All the power in this situation, Foucault asserts, lies with the spectator, in this case Eric. From this first encounter with Kilmeny, his gaze focuses on her physical features, and he takes an almost voyeuristic enjoyment in the sight as he watches her, while she remains unaware of his presence. From this moment forward, Eric’s visual pleasure is aesthetic, viewing and possessing Kilmeny as his own exclusive, beautiful painting created and positioned for his eyes only. While he watches her unseen, suggestively hidden in “the shadow of the apple tree,” his impressions are conveyed in artistic language that focuses on Kilmeny’s face, as if captured in a carving or a painting: It is “oval, marked in every cameo-like line and feature with that expression of absolute, flawless purity, found in the angels and Madonnas of old paintings, a purity that held in it no faintest stain of earthliness.” In addition to words such as “cameo,” “line,” “feature,” and “paintings,” Eric’s first glimpse of Kilmeny is relayed through language such as “delicately pencilled,” “purely tinted,” “pale blue print,” “shape and texture,” “wavering shadow,” and “flower-like,”12 all of which suggest either the details a painter or sculptor might feature in creating an artwork, or specific techniques that render those details. Like a Renaissance religious painting, with its clean lines and symmetry of light and dark, Eric’s interpretation of Kilmeny’s face is that of an artistically rendered angel or Madonna. Many members of the Lindsay community have never seen Kilmeny because her mother and then her aunt and uncle hid her from the public eye. Even Mrs. Williamson, Eric’s landlady, who considers herself to have been a close friend of Kilmeny’s mother, has “never laid eyes on her.”13 Eric therefore is in sole possession of this image of Kilmeny and can shape it and her as he wishes. Moreover, placed in what seems to be an ethereal space in the old orchard, the Kilmeny Eric conceptualizes is visually static. As an otherworldly art object, she seems to exist specifically to invite the spectator’s—Eric’s—gaze with no control over the development of her identity or future.

Artworks portraying women often invite the viewer’s gaze by including a spectator inside the image itself.14 In Ways of Seeing, John Berger reflects on two different paintings by Jacopo Tintoretto, both on the biblical subject of “Susannah and the Elders,” in which the elders are visible but hidden, watching Susannah bathe. At the same time, Berger points out, we the viewing audience “join the Elders to spy on Susannah.”15

Likewise, visual-cultural theorists Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright, discussing Diego Velázquez’s painting Las Meninas, direct our attention to several different visible and hidden spectators within the painting, including the child’s maids, her parents (reflected in a mirror on the wall), and the portrait painter, whom we cannot see but whose easel is cut off by the frame.

Sturken and Cartwright suggest that the viewer is both gazing and being gazed at, therefore being forced by Velázquez to take on the role of visible yet hidden spectators in the painting, perhaps that of the parents.16 In Kilmeny, the narrator’s verbal images of Kilmeny as artwork operate as ekphrasis, or the vivid description of a work of art, and function in a similar way to the paintings discussed by these visual-cultural theorists by first presenting us with a spectator inside the “painting” —Eric—and then inviting us to gaze on Kilmeny as if we, too, are Eric. Additionally, readers take on the role of spectator by seeing the entire scene from without, gazing on both Kilmeny and Eric.

Philosopher and film studies scholar Kelly Oliver addresses such privileged situating of male characters as both artist and critic as one reason the male gaze must still be reckoned with in the twenty-first century: It anchors the role of that gaze in controlling events in an artwork or story. In her depiction of Eric in Kilmeny of the Orchard, Montgomery, like the often male producer of images and text, “puts all spectators in the position of men looking at women, identifying as male and desiring the female.”17 Readers must view Kilmeny through Eric’s eyes to become acquainted with her, forcing them into the position of the male agent. The novel’s perspective directs readers to connect with Eric and perhaps even adopt his attitudes toward her. If readers resist connecting with the male gaze and instead reposition themselves with Kilmeny, they are vicariously subjected to the control of the gaze in the story because she is in that position. The lack of agency and change in the primary female character is unusual in Montgomery’s work and can result in a feeling that the whole story is a disconcerting painting of a painting.

Eric’s pleasure as an active spectator of Kilmeny is emphasized in the narrator’s statement that he “could not tell which was the greater pleasure”—to listen to her play the violin or to look at her. “Her beauty,” the narrator remarks, was “more wonderful than any pictured loveliness he had ever seen” because each “tint and curve and outline of her face was flawless.”18 This description of her with such unearthly, even immortal perfection aligns with the title of an earlier chapter, “A phantom of delight,”19 that references William Wordsworth’s poem, in which the subject is described simultaneously as “a perfect Woman, nobly planned” and “a Spirit still, and bright / with something of Angelic light.”20 Since the kind of perfection that Eric projects onto Kilmeny is unattainable in the human form, readers may find themselves questioning the pictures that this once proudly practical, level-headed man has created. Is there ironic tension between the narrator’s alignment with a smitten Eric’s idealistic perspective and the authorial presence behind both? As Epperly concludes about the novel’s formulaic romantic characterization and structure, “Montgomery outgrew this formula (had outgrown it, really), even if she did not put aside all the cultural assumptions encoded in Kilmeny.”21 Or is Eric simply a twentieth-century Pygmalion, and Kilmeny his Galatea? Given the “cultural assumptions” that Epperly mentions, are readers, similar to the Lindsay community, never to see Kilmeny from any perspective but that of the infatuated Eric?

For Eric, the picture he first creates remains fixed because, “[i]n the intervals of absence,” he takes pleasure in the memory of Kilmeny’s beauty and in anticipating whether he remembers her accurately, thinking that she “could not possibly be as beautiful as he remembered her.”22 As Berger posits in Ways of Seeing, an image is “an appearance, or a set of appearances, which has been detached from the place and time in which it first made its appearance and preserved—for a few moments or a few centuries.”23 Eric preserves Kilmeny’s beauty in memory by freezing her in one place and time. The preservation of Kilmeny in Eric’s memory—in the orchard, in the moments when he gazes at her and listens to her music—parallels the way he has preserved his mother in his memory. Mrs. Marshall, who died when Eric was ten, is kept in the forefront of her husband’s and son’s minds and, as noted earlier, sets a standard of beauty and character through her picture hanging in the family home. However, Roland Barthes, writing in Camera Lucida, declares that a picture is “never, in essence, a memory … but it actually blocks memory, quickly becomes a counter-memory.”24 The picture of Eric’s mother thus becomes what Geoffrey Batchen calls a “frozen” illustration, “set in the past,” which “replaces the unpredictable thrill of memory with the dull certainties of history” because it eliminates the emotional responses that sensory memories of smell or sound can evoke.25

Eric’s memory of Kilmeny’s beauty therefore leaves him feeling detached from her when she is not physically present, and she becomes more and more like his mother’s picture and memory, an ethereal objet d’art, and less and less a real woman: “Eric Marshall seemed to himself to be living two lives,” one in a changing, “workaday” world, the other “spent in an old orchard, grassy and overgrown, where the minutes seemed to lag for sheer love of the spot and the June winds made wild harping in the old spruces.” Moreover, to inhabit both these worlds, he now “possesse[s] a double personality.”26 It is as if Eric has moved into the painting with Kilmeny in the orchard when he is not engaged in everyday activities and communing with his pupils and neighbours. While in this painting, he assumes not just dual but multiple spectating roles, like those captured in Las Meninas: He is the artist, whose easel is both inside and outside the painting, creating the portrait; he is one of the spectators painted into the scene, actively watching the subject who is being painted; and when Kilmeny is absent, he is a viewer gazing in from outside of the painting. Yet even in this last position, as the man who scripts, frames, and preserves the memory, he is the active subject in his relationship with Kilmeny, whereas she, the memory, is passive and lacks agency. She is objectified by his gaze even when she is not present with him because she has been detached from her surroundings and exists only as a memory.

The Objectification and Othering of Kilmeny

Whether as artwork or memory, Kilmeny, as perceived through the lens of Eric’s mental image, is not a real woman. Further objectification occurs from the outset with his framing her as a natural element, the “very incarnation of Spring—as if all the shimmer of young leaves and glow of young mornings and evanescent sweetness of young blossoms in a thousand springs had been embodied in her,”27 reminiscent of Botticelli’s Primavera.

As well as viewing Kilmeny from the perspective of an artist, Eric assumes two other perspectives that objectify and subject her to the male gaze. The first of these is the perspective of the experienced adult regarding a naive child. Eric’s position of power from the centre of the Foucauldian panopticon is intensified because Kilmeny lacks a clear view of herself and therefore sees herself through others’ eyes, as might an unformed and uninformed child. In the first scene when Eric sees her, she appears “childlike,” and, after startling her, he speaks to her “as he would to a child” to soothe her. Whereas he thinks of other females he encounters as girls or women, Kilmeny is “a beautiful, ignorant child.”28 Many childhood-studies theorists argue that children have historically been—and still are—viewed as “other,” as something which remains unchanged until adults begin to shape the child, and that childhood was considered a subservient and dependent state to adulthood,29 arguments that have been challenged in Marah Gubar’s Artful Dodgers: Reconceiving the Golden Age of Children’s Literature and in Lesley Clement’s introduction to (and throughout) Children and Childhoods in L.M. Montgomery: Continuing Conversations. While many of Montgomery’s novels have situations in which children are dominated by adults, they are usually autonomous thinkers who take centre stage and control important aspects of their own destinies, perhaps another reason Montgomery found Kilmeny a “doubtful experiment” and readers find it uncomfortable.30

Eric’s view of Kilmeny as a child increases the power of his gaze because it positions him to make choices based on his desires about who she is and how she will conduct herself. In fact, she at first seems to have no desires of her own, except yearning to be beautiful—to be an object of pleasure to the male gaze. Ironically, she has learned this lack of self-worth from her mother’s past treatment of her. While her mother, Margaret, hoped to spare Kilmeny the pain and humiliation she herself associated with beauty, her insistence that Kilmeny believe herself to be ugly and therefore undesirable influences Kilmeny to long for beauty and desirability. Both her yearning to be beautiful and her perception of herself as unattractive cause her to fear the gaze as much as she desires it. It is therefore easy for Eric to assume the role of teacher and manipulate and patronize her. Even when he thinks she has matured enough for him to express his love and propose marriage, he still patronizes her, calling her ideas “absurd fanc[ies]” and diminishing her by mockingly referring to her mind as “that dear black head of yours.”31 He “reassert[s] the controlling gaze of the masculine subject (as evinced in the author/reader gaze) over the feminine object.”32

Equally problematic as Eric’s treatment of Kilmeny as a child is the second perspective that objectifies and diminishes her: his repeated descriptions that align her with a feral animal. Citing Derrida’s theory that “[m]an calls himself man only by drawing limits excluding his other from the play of supplementarity: the purity of nature, of animality, primitivism, childhood, madness, divinity,” Perry Nodelman shows how children are often othered by linking them with animals.33 The narrator refers to the frightened Kilmeny, when Eric first encounters her in the orchard, as having “the expression of some trapped wild thing,” preparing for Eric’s response during his next encounter that this “wild thing” can be tamed: “When she lifted her head, he expected to see her shrink and flee, but she did not do so, she only grew a little paler and stood motionless, watching him intently.” These descriptions of Kilmeny as a wild creature are not limited to the narrator’s and Eric’s viewpoints. Kilmeny perpetuates the image of herself as a wordless child or animal when she is writing to Eric about her inability to speak and refers to the “little cries” she makes to express pleasure or fear.34 This childlike/animal-like vocalization intensifies her otherness and vulnerability by emphasizing her lacks in comparison to other adults and intensifies her role as an object, which Eric can shape through his gaze.

At the Looking Glass

In contrast to her mother, who fears beauty and makes Kilmeny believe she is ugly to try to protect her against men, Eric is the source of Kilmeny’s changing understanding of what Lacan would call her “imago,” the developing ability of an infant to identify itself as an individual.35 In a pivotal scene, Eric prepares to introduce Kilmeny to a mirror in response to her lamenting her perceived ugliness. “Beauty isn’t everything,” he says, to which she retorts, “Oh, it is a great deal.”36 Given his fixation on her beauty throughout the novel, his dismissal of its significance is either disingenuous, revealing a man who does not know his own desires and intentions, or manipulative. This ambiguity creates irony in the scene, directing the reader’s attention back to the conclusion of an early conversation Eric has with his friend David, who lays out a series of important characteristics for Eric’s future wife “to fill [his] mother’s place.” These include a “good and strong and true” personality and good looks, especially “the eyes of a woman who could love in a way that would be worth while.” Eric “carelessly” agrees with David’s assessment, acknowledging that he “could not marry any woman who did not fulfil those conditions,” establishing that he (subconsciously, at least) considers appearance to be important.37 When Kilmeny responds as she does to Eric’s dismissal of beauty as important, she inadvertently reveals, to the reader, the ironic tension between Eric’s words and his ideology, doubly ironic because Eric seems to remain unaware of his own conflicting ideas. He continues to refer to her as a lovely child, while the reader sees that he views her as a beautiful and desirable woman who may fulfil some (if not all) of the characteristics David and Eric agreed are non-negotiable in Eric’s future wife.

Berger argues that women have “almost continually been accompanied by [their] own image of [themselves].”38 Kilmeny’s self-identification is consistently negative, resulting in her debilitating fear of being seen by others. Psychologist Rachel Calogero explores the “multitude of negative consequences for women” of “the implicit and explicit sexual objectification of the female body in Western culture,” arguing that, “[t]he primary psychological consequence … is the development of an unnatural perspective on the self known as self-objectification. Women who self-objectify have internalized observers’ perspectives on their bodies and chronically monitor themselves in anticipation of how others will judge their appearance, and subsequently treat them.”39 Always worried about how others perceive her, Kilmeny has internalized others’ perspectives, as studies such as Calogero’s show happening for many women. Having no real reference point for her own appearance, other than her mother’s that she is unattractive and unappealing, Kilmeny internalizes this perception and interprets all other encounters she has with people as further confirmations of her ugliness.40 Eric provides her an alternative perspective, although one that still focuses on external appearance. Eric’s gaze is transformative, but in the way that E. Ann Kaplan observes in Women and Film: “[M]en do not simply look; their gaze carries with it the power of action and of possession which is lacking in the female gaze.”41

When viewed through the lens of Lacanian theory, Eric’s “power of action and of possession,” epitomized in the mirror scene, is problematized. Kilmeny has never seen herself reflected in a proper mirror before she meets Eric, only in distorting objects like spoons and the sugar bowl, because her mother broke all mirrors.42 Lacan theorizes that the “mirror stage,” a phase occurring between six and eighteen months when infants begin to recognize themselves as individuals in a mirror, is crucial in the development of human identity. Until then, an infant is “still sunk in his motor incapacity and nursling dependence,” non-verbal and passive.43 Kilmeny has developed skills to communicate with others through writing on a slate, but like Lacan’s infant, she lacks physical speech, the vocal expression of language, a significant human communicative tool. Indeed, Kilmeny says that she has tried to speak words but “never can make [her] tongue say them.”44 It seems that she lacks the necessary motor skills to form words or that these skills are as yet undeveloped. Eric discovers that Kilmeny’s family believes she has been cursed with silence because of her mother’s transgressions, circumstances that have led to her isolation and dependence on relatives.45 In Lacan’s terms, Kilmeny is still in a state of “nursling dependence” on adults for protection and survival before beginning the process of individualizing following the mirror stage.

Eric’s decision to purchase a mirror and hang it in the Gordon home, where Kilmeny can frequently view herself, puts her in a position to “connive in treating herself as, first and foremost, a sight,” as Berger observes about other female subjects.46 Eric now stages the scene, but unlike the earlier scenes in the orchard when she is unaware of his staging, here she is a complicit participant. First are the costumes: “I want you to … put on that muslin dress you wore last Sunday evening, and pin up your hair the same way you did then.” He persists in setting the scene based on past encounters and his memories of them, now more a director or stage manager than an artist. He continues to see her as a small child, scolding and admonishing her to wait in the wings before she enters the scene: “Run along—don’t wait for me. But you are not to go into the parlour until I come.” He carefully stages each step of the design process that will lead to the perfect tableau when Kilmeny first sees herself in the mirror. As she comes down the stairs, “[h]er marvellous loveliness was brought out into brilliant relief by the dark wood work and shadows of the dim old hall.”47 He has frozen the scene again through chiaroscuro, artistic effects that make a figure appear detached, in relief, from the background of the painting. Whereas Kilmeny has earlier been described as “cameo-like”—a more muted relief because the medium is often ivory and lacks strong contrasting colours—here his image of her in relief completely detaches her from her everyday life.

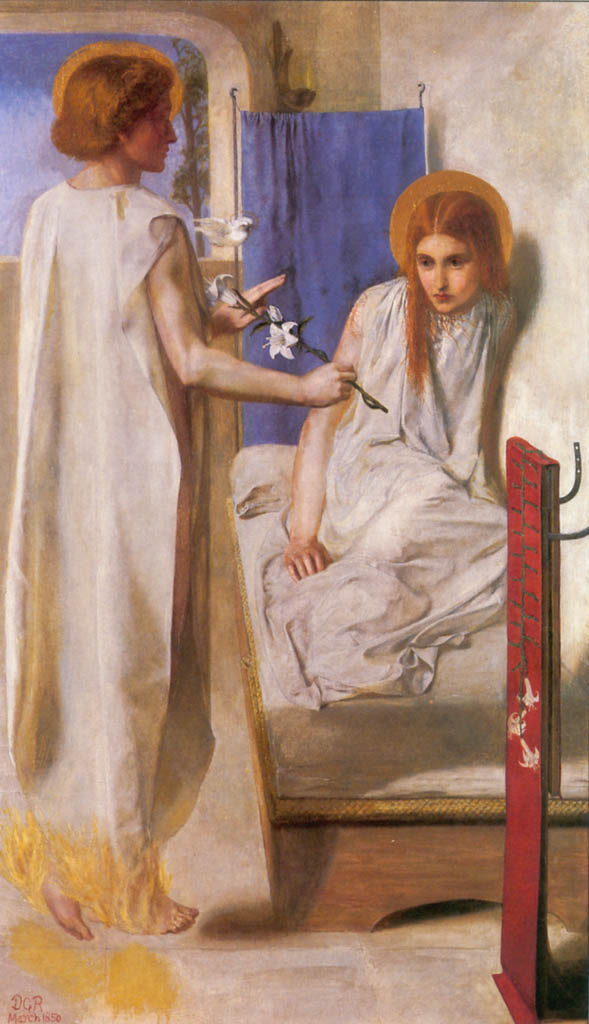

Eric further instructs/constructs Kilmeny as he prepares her to look in the mirror: “Take these lilies on your arm, letting their bloom fall against your shoulder—so.” The lilies are referred to as both “Mary-lilies” and “Madonna lilies,”48 alluding to well-known pre-Raphaelite paintings of the Annunciation, such as Dante Gabriel Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini! and John William Waterhouse’s Annunciation, in which the angel Gabriel offers Mary white lilies.

Eric’s staging of this scene also recalls his first encounter with her, when he thought she looked like a Madonna painting,49 once again indicating that she is, for him, as much a memory as a real woman. As a final artistic touch, Eric places Kilmeny in front of the mirror, where she will be “a lovely picture in a golden frame,”50 his revealing of her to herself as an artwork he has designed. The power of the male gaze is further perpetuated by Eric’s position when Kilmeny first sees herself in the mirror. By leading her to the mirror and standing near enough to her to pull her hands from her eyes, he situates himself in such a way as both to watch her reflection in the mirror and to watch her response to her reflection. He assumes the active/male spectator role Mulvey describes, while Kilmeny, standing in front of the mirror, attired as Eric desires and unable to move in her first surprise, is the passive/female object.51

This scene distinguishes between the gaze and the glance, whereby a gaze is “sustained” and “intent,”52 implying that the spectator has a bold and prolonged interest in examining the object upon which (in this case) he gazes, while a glance is quick, often “furtive” or “sideways,”53 suggesting hesitancy about the experience of looking. Eric represents the long, sustained “gaze” as he intently studies and watches Kilmeny throughout her introduction to the mirror. However, Kilmeny’s own response to herself is specifically referred to as a glance, as she continually “steal[s] shy radiant glances at the mirror.”54 Her body language demonstrates uncertainty about the propriety of looking at herself, while simultaneously reflecting her eagerness to see herself as others see her. She has become part of what Sturken and Cartwright call the “field of the gaze” because she is now “present and looking”55 at herself with Eric, but she also remains the object of the gaze. Furthermore, to avoid being considered vain, she must engage only in glancing, not gazing: “Don’t look into it too often,” Eric warns her, “or Aunt Janet will disapprove. She’s afraid it will make you vain.”56 Kilmeny’s unearthly beauty and purity, like her alignment with the Virgin Mary of past artwork, can be maintained only if she keeps her eyes (mostly) averted from the image in the mirror, imitating the downcast glance of the Madonna in Annunciation paintings such as Rosetti’s Ecce Ancilla Domini! In cautioning her not to look “too often,” Eric suggests that her new, Eve-like awareness of herself and her appearance must be controlled so as not to taint her. Berger observes that, in artwork, the “mirror was often used as a symbol of the vanity of woman” but that such “moralizing” by the predominantly male artists/spectators “was mostly hypocritical.”57 Berger’s assessment of “hypocritical” moralizing aptly applies to Eric because he has provided Kilmeny with the tools for glancing at herself and then warns her against using them.

Metaphorically and psychologically, Kilmeny’s desire to view herself in the mirror is an essential step toward becoming Lacan’s “Ideal-I.” Lacan argues that a child takes a “jubilant assumption of [the] specular image” in playing at the mirror, learning “the relation between the movements assumed in the image and the reflected environment, and between this virtual complex and the reality it reduplicates—the child’s own body, and the persons and things around [the child].”58 The description of Kilmeny recognizing her own image in the mirror, the core of Lacan’s mirror stage, is clearly one of a child taking “jubilant” pleasure in herself. She blushes, smiles, laughs, thinks the mirror is “wonderful,” spends time “lingering there dreamily,” and expresses gladness to her aunt in discovering that she is “not ugly.”59 Eric has shown Kilmeny what he sees and, in enacting the moment when Kilmeny reaches Lacan’s mirror stage, has played a significant role in “the constitution of [her] ego.”60

Not Her Own Voice or Image

Kilmeny’s discovery of her image in the mirror is key to the remainder of the narrative. Lacan asserts that the child’s moment of joyful recognition of the self in the mirror must happen “before language restores to [the child] … its function as subject.” In other words, the mirror stage precedes recognizable vocal speech.61 The pivotal moment for Kilmeny occurs only after she has viewed herself in the mirror: She gains the ability to speak when she observes the Gordons’ hired hand and foster son, Neil, about to kill Eric. Now that she has an imago she, at least momentarily, becomes an active subject in her own story through the use of spoken (not written) language. She also temporarily becomes the spectator: While she sees Eric from across the orchard, from a similar vantage point as when he first saw her, Eric does not see her. Indeed, for just a moment, the scenario playing out in front of Kilmeny becomes a work of art, just as she has been a work of art to Eric for so long. Neil’s murderous intent “photographed itself in her brain in an instant.” Yet even in this scene, the perspective shifts back to Eric’s viewing Kilmeny as a piece of art. When Kilmeny first sees Eric sitting across the orchard, she blushes, but “the next moment [the blush] ebbed, leaving her white as marble. Horror filled her eyes—blank, deadly horror, as the livid shadow of a cloud might fill two blue pools” when she sees Neil holding an axe over Eric.62 Her momentary role as the spectator is short-lived, and Kilmeny becomes like Pygmalion’s statue of Galatea, not only in bodily appearance and stance but also in the ivory (or marble) whiteness of her skin.63 Then, just as Venus infused Galatea with life at Pygmalion’s request, so speech rises up within Kilmeny, as if in response to Eric’s deepest wish, and she screams his name, warning him of danger.64 It seems that Kilmeny must view herself as Eric views her to develop enough passion for Eric, a depth of emotion that would “break the fetter,” as the final chapter title indicates.

Achieving speech empowers her to act for Eric, giving her the ability to “function as a subject,” a function, according to Lacan, that speech “restores” only after an infant has recognized the image of herself in a mirror.65 Thus the mirror stage, instigated through Eric’s desire for her to view herself, becomes an instrument of Eric’s gaze which effects Kilmeny’s ostensible transition from child to woman, just as Pygmalion’s prayers to Venus are the implement of Galatea’s transformation from ivory to flesh-and-blood. Although Kilmeny’s speech and voice emanate from her, they are not her voice but an echo of what Eric and society have created and scripted. Aptly, the first words she speaks are his name and a warning to him. Furthermore, her continued delight in her newfound ability to speak is almost entirely focused on the pleasure she can bring to Eric—she can express love to him, she is happy that her first word has been his name, and she now sees herself as worthy to marry him.66 The artwork Eric has created has come to life in the manner of his choosing, rather than her own.

The New Picture in the Family Portrait Gallery

Now that Eric has fulfilled the criteria for turning Kilmeny into an ideal portrait of womanhood, akin to his dead mother, Kilmeny is prepared to be scrutinized by Eric’s father. Before he assumes the role of spectator, Mr. Marshall’s detachment from Kilmeny is almost absolute—not only has he never seen her, but Eric has never written about her until shortly before Mr. Marshall visits. The only descriptive detail Eric gives his father before they visit the orchard is that “Kilmeny’s mouth is like a love-song made incarnate in sweet flesh.” Thus, for Mr. Marshall, Kilmeny is primarily an as-yet-unseen art object. When he first sees her, while she looks very beautiful and meets his eyes with a “frank gaze,” it “waver[s] before the intensity of his keen old eyes.” In contrast to Kilmeny’s inability to maintain eye contact for very long, Mr. Marshall’s gaze “pierces,” is “steady,” “intense,” and “keen.” Mr. Marshall’s gaze is that of the male critic. Eric has staged this intense scrutiny of Kilmeny by providing his father with so few details. His evasiveness leads Mr. Marshall to say, “I shall look at her with the eyes of sixty-five, mind you, not the eyes of twenty-four. And if she isn’t what your wife ought to be, you give her up or paddle your own canoe.”67 Through Eric’s gaze, Kilmeny has been shaped into the desired portrait of womanhood. Now Mr. Marshall can assess the quality of the work and approve hanging the portrait in the gallery, as indicated by Eric’s marriage to Kilmeny and their subsequent return to his home.

From Eric’s perspective, Kilmeny has “develop[ed] and blossom[ed] under his eyes, like some rare flower, until in the space of three short months, she ha[s] passed from exquisite childhood into still more exquisite womanhood.” She has even begun to speak, and she has passed his father’s critique. But in that process, she has not become autonomous. “Under his eyes” reinforces that his gaze has been the force guiding her through stages of controlled change. Now as a woman, Kilmeny is still subjected, or submissive, to Eric, still “under” his controlling gaze. She has been shaped to leave Lindsay and her old life, now to be put on display in Eric’s home and world. She can “fill [his] mother’s place,” a place currently occupied by a picture on the wall and by what Barthes would call a “counter-memory” that blocks Kilmeny from ever becoming anything more than a portrait.68

Conclusion

While Montgomery seems to have brought about a happy resolution to this formula romance, the way Eric views Kilmeny following her supposed transformation into adult woman changes only slightly. Eric still sees her as an object to be gazed upon and a child to be hidden away where no one else can see her, either by keeping her in the old Connors orchard perpetually or by removing her from Lindsay as quickly as possible.69 As the man, he believes he has the power and right to maintain or shift “the field of the gaze,”70 to expand, as the final words of the story say, “the vista of his future” enough to grant her a place among his family portraits. Specifically, Eric feels that he should have control over the people allowed to see Kilmeny, arguing to himself that both the community of Lindsay and the outside world are a negative field of the gaze, “with just the same pettiness of thought and feeling and opinion at the bottom of it.”71 He fears that if Kilmeny is allowed out of the seclusion in which she has been raised and kept, he will lose control over how she is to be viewed. He will no longer be able to determine, in Sturken and Cartwright’s words, “who is present, who stands where, what hangs on the walls, how the show is organized, and who is drawn or permitted to walk and look where.”72 And so the novel ends with references to the gaze which suggest that Kilmeny will eternally remain a piece of art in need of male approval: “[O]n [Eric’s] face was a light as of one who sees a great glory widening and deepening down into the vista of his future.”73 His gaze is sustained indefinitely, and the subject of the painting is fixed forever in that gaze. She cannot move without male approval, she cannot change and develop without male guidance, and she will always be watched and judged based on her appearance.

About the Author: Heidi A. Lawrence studies the intersections between ecopsychology and its praxis, ecotherapy, and children’s and adolescent literature, with special interest in imaginative and fantastic literature. She considers the ways in which reading these literatures may allow audiences to reimagine their connections with the non-human, leading to more ecologically conscious behaviours and to a greater degree of mental, physical, and emotional well-being. She has participated in international literature conferences, including the L.M. Montgomery Institute, MLA, IRSCL, ChLA, and ASLE, presenting on Montgomery, Louisa May Alcott, Madeleine L’Engle, and other children’s literature authors. She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature (University of Glasgow, UK), M.A. degrees in English (Brigham Young University) and Medieval Studies (University of Leeds, UK), and an M.Phil. in English Literature (University of York, UK). She works as adjunct faculty at Brigham Young University.

Banner Image: Book cover of Kilmeny of the Orchard, 1910. kindredspaces.ca, 532 KO-PG-1ST.

- 1 For a history of the publication of Kilmeny of the Orchard, see Cavert, “Bertie” 6; Epperly, Through 55; Mahon, “Miss” 43n9; Rubio, Lucy Maud 131; Waterston, “Lucy Maud” 56; and Waterston, Magic Island 31.

- 2 Montgomery, CJ 2 (23 Dec. 1909): 242.

- 3 Montgomery, CJ 2 (6 Jan. 1910): 248; (19 Mar. 1910): 290; (4 May 1910): 297; (27 Jan. 1911): 357; (23 May 1911): 404; CJ 5 (1 Sept. 1924): 283; CJ 6 (2 Dec. 1926): 100.

- 4 Montgomery, CJ 7 (1 Mar. 1930): 13–14.

- 5 Waterston, Magic Island 30–38; Rubio 131–32.

- 6 Epperly, Fragrance 228, 231, 229. Kilmeny is, therefore, like the many artistic renderings of medieval romance in the Victorian era, such as the pre-Raphaelite fondness for the Lancelot and Elaine and Lady of Shalott stories.

- 7 Mulvey, “Visual” 8–10, 11–12. Although fifty years since its original publication, Mulvey’s essay is still reissued, cited, continually engaged with, and challenged. For a sampling of twenty-first-century critics who draw on Mulvey, see Klorman-Eraqi, “Feminist” 16; Cummins, “Women’s” 24, 39.

- 8 See, for example, the three McKenzie articles in the Works Cited.

- 9 See, for example, K.L. Poe, “Who’s Got the Power?”

- 10 Montgomery, KO 5; 12–13.

- 11 Foucault, Discipline 201–02.

- 12 Montgomery, KO 30–32.

- 13 Montgomery, KO 38.

- 14 Berger, Ways 36–37, 43; McGowan, “Looking” 28–29.

- 15 Berger 50.

- 16 Sturken and Cartwright, Practices 105–07.

- 17 Oliver, “The Male” 451.

- 18 Montgomery, KO 56.

- 19 Montgomery, KO 27.

- 20 Wordsworth, “She Was a Phantom of Delight” lines 27, 29–30.

- 21 Epperly, Fragrance 229.

- 22 Montgomery, KO 61–62.

- 23 Berger 9–10.

- 24 Barthes, Camera 91.

- 25 Batchen, Forget 15.

- 26 Montgomery, KO 61.

- 27 Montgomery, KO 48.

- 28 Montgomery, KO 2, 35, 48, 96–97.

- 29 See Nodelman, “The Other” 31; Thacker, “Feminine” 3, 5.

- 30 There are many examples of such children throughout her works, among them Emily Byrd Starr, who refuses to stop writing; Anne Shirley, who changes the lives and worlds of Matthew and Marilla Cuthbert, as well as of others wherever she goes; Sara Stanley, whose stories put her on the path to fame; and Jane Stuart, who ultimately overcomes her cruel grandmother to reunite her mother and father.

- 31 Montgomery, KO 105.

- 32 Taylor, “Considering” 76.

- 33 Nodelman 34.

- 34 Montgomery, KO 32, 47; 58.

- 35 Lacan, “The Mirror Stage” 2.

- 36 Montgomery, KO 67.

- 37 Montgomery, KO 8.

- 38 Berger 46.

- 39 Calogero, “A Test” 16.

- 40 See, for example, her response to the egg peddler, Montgomery, KO 66.

- 41 Kaplan, Women 31.

- 42 Montgomery, KO 66–67, 96.

- 43 Lacan 1–2.

- 44 Montgomery, KO 58.

- 45 Montgomery, KO 109–13.

- 46 Berger 51.

- 47 Montgomery, KO 99.

- 48 Montgomery, KO 100, 99.

- 49 Montgomery, KO 31.

- 50 Montgomery, KO 100.

- 51 Mulvey 19.

- 52 Sturken and Cartwright 103.

- 53 Bryson, Vision 94.

- 54 Montgomery, KO 101 (emphasis added).

- 55 Sturken and Cartwright 103.

- 56 Montgomery, KO 101.

- 57 Berger 51.

- 58 Lacan 2.

- 59 Montgomery, KO 101–02.

- 60 Mulvey 17.

- 61 Lacan 2.

- 62 Montgomery, KO 125, 126.

- 63 Ovid, “The Story” lines 248–49.

- 64 Montgomery, KO 126.

- 65 Lacan 2.

- 66 Montgomery, KO 126–31.

- 67 Montgomery, KO 133, 134.

- 68 Montgomery, KO 124, 132, 12–13; Barthes 91.

- 69 Montgomery, KO 96, 131–32.

- 70 Sturken and Cartwright 103.

- 71 Montgomery, KO 96.

- 72 Sturken and Cartwright 104.

- 73 Montgomery, KO 134.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Translated by Richard Howard. Hill and Wang, 1980.

Batchen, Geoffrey. Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance. Princeton Architectural P, 2004.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. Penguin, 1977.

Bryson, Norman. Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze. Macmillan, 1983.

Calogero, Rachel M. “A Test of Objectification Theory: The Effect of the Male Gaze on Appearance Concerns in College Women.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, vol. 28, 2004, pp. 16–21.

Cavert, Mary Beth. “Bertie McIntyre.” The Shining Scroll, 2005, pp. 6–11.

Clement, Lesley D., et al. Introduction. Children and Childhoods in L.M. Montgomery: Continuing Conversations, edited by Rita Bode et al. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2022, pp. 3–23.

Cummins, Kathleen. “Women’s Storytelling—Narrative, Genre, and Female Voice.” Herstories on Screen: Feminist Subversions of Frontier Myths, edited by Cummins, Columbia UP, 2020, pp. 20–97.

Epperly, Elizabeth Rollins. The Fragrance of Sweet-Grass: L.M. Montgomery’s Heroines and the Pursuit of Romance. U of Toronto P, 2014.

---. Through Lover’s Lane: L.M. Montgomery’s Photography and Visual Imagination. U of Toronto P, 2007.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Pantheon, 1977.

Gubar, Marah. Artful Dodgers: Reconceiving the Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Oxford UP, 2009.

Kaplan, E. Ann. Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera. Methuen, 1983.

Klorman-Eraqi, Na’ama. “Feminist Photography and the Media.” The Visual Is Political: Feminist Photography and Countercultural Activity in 1970s Britain, edited by Klorman-Eraqi, Rutgers UP, 2019, pp. 12–51.

Lacan, Jacques. “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience.” Écrits: A Selection, translated by Alan Sheridan, Routledge, 2007.

Mahon, A. Wylie. “Miss Montgomery, the Author of the ‘Anne’ Books.” The L.M. Montgomery Reader. Volume 1: A Life in Print, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 2013, pp. 40–43.

McGowan, Todd. “Looking for the Gaze: Lacanian Film Theory and Its Vicissitudes.” Cinema Journal, vol. 42, no. 3, 2003, pp. 27–47.

McKenzie, Andrea. “The Changing Faces of Canadian Children: Pictures, Power, and Pedagogy.” Windows and Words: A Look at Canadian Children’s Literature in English, edited by Aïda Hudson and Susan-Ann Cooper, U of Ottawa P, 2003, pp. 201–18.

---. “Patterns, Power, and Paradox: International Book Covers of Anne of Green Gables Across a Century.” Textual Transformations in Children’s Literature: Adaptations, Translations, Reconsiderations, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, Routledge, Taylor and Francis, 2013, pp. 127–53.

---. “Writing in Pictures: International Images of Emily.” Making Avonlea: L.M. Montgomery and Popular Culture, edited by Irene Gammel, U of Toronto P, 2002, pp. 99–113.

Montgomery, L.M. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911 [CJ 2], edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, Oxford UP Canada, 1985–1987.

---. Kilmeny of the Orchard. Seal, 1987.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1922–1925 [CJ 5], edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills, 2018.

---. LM. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1926–1929 [CL 6], edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills, 2017.

---. L.M. Montgomery’s Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1930–1933 [CJ 7], edited by Jen Rubio, Rock’s Mills, 2019.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, 1975, pp. 6–18.

Nodelman, Perry. “The Other: Orientalism, Colonialism, and Children’s Literature.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly, vol. 17, no.1, 1992, pp. 29–35.

Oliver, Kelly. “The Male Gaze Is More Relevant, and More Dangerous, than Ever.” New Review of Film and Television Studies, vol. 15, no. 4, 2017, pp. 451–55.

Ovid. “The Story of Pygmalion.” Metamorphoses, translated by Rolfe Humphries, Indiana UP, 2018, pp. 241–43.

Poe, K.L. “Who’s Got the Power? Montgomery, Sullivan, and the Unsuspecting Viewer.” Making Avonlea: L.M. Montgomery and Popular Culture, edited by Irene Gammel, U of Toronto P, 2002, pp. 145–59.

“Relief.” Oxford English Dictionary. 2020. https://www-oed-com.erl.lib.byu.edu/view/Entry/161918?rskey=9uInwu&resu….

Rubio, Mary Henley. Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings. Anchor Canada, 2010.

“Scopophilia.” Oxford English Dictionary. 2020. https://www-oed-com.erl.lib.byu.edu/view/Entry/172997?redirectedFrom=sc….

Sturken, Marita, and Lisa Cartwright. Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture. Oxford UP, 2018.

Taylor, Megan Mooney. “Considering the Triangular Masculine Controlling Gaze: Gendered Authorial Intent in Norman Lindsay’s The Cousin from Fiji and Dust or Polish?” Hecate, vol. 42, no. 1/2, 2018, pp. 76–84.

Thacker, Deborah. “Feminine Language and the Politics of Children’s Literature.” The Lion and the Unicorn, vol. 25 no.1, 2001, pp. 3–16.

Waterston, Elizabeth. “Leaskdale: L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valley.” L.M. Montgomery’s Rainbow Valleys: The Ontario Years, 1911–1942, edited by Rita Bode and Lesley D. Clement, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2015, pp. 21–32.

---. “Lucy Maud Montgomery 1874–1942.” The L.M. Montgomery Reader. Volume 2: A Critical Heritage, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 2014, pp. 51–74.

---. Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery, Oxford UP, 2008.

Wordsworth, William. “She Was a Phantom of Delight.” https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45550/she-was-a-phantom-of-delig….

Article Info

Copyright: [Heidi A. Lawrence], [2022]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.

Copyright: [Heidi A. Lawrence], [2022]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (Creative Commons BY 4.0), which allows the user to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, PROVIDED the Licensor is given attribution in accordance with the terms and conditions of the CC BY 4.0.