There is likely no version of Anne of Green Gables more mythologized than Muraoka Hanako’s 1952 Japanese translation, Akage no An. While many arguments have been offered to explain Anne’s Japanese success, this article moderates some of the more sensationalized while also situating the book within Japan’s wider cultural history.

“War is raging between Japan and China. There is unrest everywhere. It is surely a tortured world.”

—L.M. Montgomery, Selected Journals (23 September 1937)1

“A text that generically proffers itself as ‘true,’ as a representation of unaltered ‘reality,’ makes a perfect test case for analytical work that tries to posit or explain the fundamental fictionality of all representation.”

—Mary Baine Campbell, The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing (2002)2

Introduction

In the summer of 2019, Prince Edward Island played host to royalty. On 27 August, Princess Takamado of the Japanese royal family flew into Charlottetown for the second time in fifteen years. Officially, the princess had arrived to commemorate ninety years of diplomatic relations between Canada and Japan, Canada’s legation in Tokyo having officially opened on Canada Day, 1929.3 Over the following two days the princess took in a performance of Anne of Green Gables: The Musical at the Confederation Centre of the Arts, helped inaugurate the new Montgomery Park and Green Gables visitor centre in Cavendish, and later participated in a ceremony at the University of Prince Edward Island where, as patron of the L.M. Montgomery Institute (so granted during her previous visit), she received a plate salvaged from the 1883 wreck of the Marco Polo, an event witnessed and later recalled by Montgomery in her journal.4 It was, almost exclusively, an Anne-themed extravaganza of a visit. “The novels show us the importance of words, the power that rests in rich vocabulary, its potential to comfort and encourage but also to hurt. And that is a lesson we should all take to heart,” the princess remarked as she opened Montgomery Park. “Today when the world is subject to so much divisiveness, this homage to Lucy Maud Montgomery is most timely and relevant.”5 This was L.M. Montgomery as Prince Edward Island’s modern cultural ambassador, as well as an antidote to twenty-first century populist politics.

Today, Japan’s fascination with Anne and the Island is an unremarkable and long-accepted fact; rarely does a tourist season go by without at least one Canadian newspaper commenting on and seeking to explain the now ubiquitous phenomenon.6 “Anne of Green Gables has assumed almost mystical dimensions in the eyes of ordinary Japanese,” the Ottawa Citizen intoned in 1999, and few Canadians then or now would have likely disagreed.7 The Japanese adore Anne, the argument goes, because of their ingrained cultural valuing of rural beauty, and because Anne’s precocious and optimistic (yet respectful and traditionally minded) values strike a chord with Japanese society. As a result, Anne “has become a role model—no, an icon—for countless Japanese,” as the National Post declared in 2002. “Anne of Green Gables has inspired generations to cheerfully persevere.”8 In the words of historian Douglas Baldwin, to young Japanese women, “Cavendish is a ‘mecca,’ and some of them break into tears when they first enter Anne’s ‘home.’ Some Japanese tourists offer money to island girls for a lock of their red hair.”9 One could be forgiven for believing Anne to be a fictionalized member of the Beatles: the most famous Islander who never lived.

There is certainly truth to these accounts. Many Japanese do indeed enjoy Anne of Green Gables, and some have visited Prince Edward Island. But I believe there are important qualifications to this narrative which must also be considered. For one (and despite appearances), the Anne “phenomenon” in Japan is much less unique and spontaneous than many Canadians apparently assume. Quite simply, if L.M. Montgomery’s novels had never been translated into Japanese (a distinct possibility in retrospect), there would still have been many comparable works available to Japanese readers. For another, while it is undoubtedly true that some Japanese admire Prince Edward Island, one should not assume that they know much about Islanders or see in the Island’s landscapes the same things that residents do, or Montgomery did. In truth, regardless of their love of Anne, many Japanese can be ignorant, if not patronizing, toward Islanders. Building on recent research by scholars such as Brian Bergstrom and Uchiyama Akiko, this article explores the history of Prince Edward Island from the less familiar (at least to English speakers) Japanese perspective and contextualizes some of the more hyperbolic claims made by Canadians about both the significance of Anne and the role Prince Edward Island plays in contemporary Japanese culture. By studying both the chain of events that led to Anne’s introduction in Japan, as well as accounts by those Japanese who have visited the Island, we can gain a greater understanding of how and why this novel succeeded in a market so far removed from Montgomery’s presumed audience.

Historical Contingencies: Discovering Anne in Japan

To some extent, Japan’s adoption of Anne of Green Gables was an accidental by-product of an otherwise unsuccessful Canadian effort to have the Japanese adopt Christianity. Beginning in the late-nineteenth century, many Protestant missionary organizations took up residence in Japan to try to grow their flocks. By the interwar years, these included the United Church of Canada, the Anglican Church of Canada, and the Presbyterians. During the 1930s, however, this evangelizing was taking place against mounting hostility from the local authorities as Japan’s ultranationalism led to repression at home and wars with China in 1937 and the Western allies in 1941. As historian A. Hamish Ion has noted, it was within this “tortured world” that these missionary men and women tried to keep open “the reciprocal influences of cultural interaction despite the approaching roar of war and the harangues of xenophobes.” In the end, however, they were unsuccessful: “no Christian phoenix would rise out of the ashes once the fires of war were spent. The missionary age died in failure.” Yet, as Ion acknowledges, this does not mean that the missionaries left no impact; many had built lasting schools, hospitals, and churches during their time in Japan. Even in leisure activities the missionaries left their mark, encouraging now common Western pastimes such as hiking and tennis. The translation of Anne of Green Gables was yet another unlikely legacy of this prewar cultural interchange.10

One of the schools set up by Canadian missionaries was Tokyo’s Tōyō Eiwa Jogakkō, established by the Methodists for female converts in 1884. Despite pressure from Japanese authorities, natural disasters such as the 1923 Kantō earthquake, and the onset of the Great Depression in the early 1930s, the school prospered during the interwar years. Among the many students who passed through its gates during this period was Muraoka Hanako. After graduation, Muraoka went on to work as a teacher, writer, editor, and translator. However, despite her obvious friendships with Canadian missionaries both during and after her schooling, there was no indication during this period that she held any particular affinity for the works of L.M. Montgomery. Only in the late 1930s did Muraoka first encounter Anne of Green Gables, when the departing missionary Loretta Shaw gifted her a copy of the English original.11 It was only during the war years—when publishing foreign works was out of step with the government’s ultranationalist policies—that Muraoka quietly translated Anne. Her resulting translation, Akage no An [Red-Haired Anne] was eventually published in 195212 at the tail end of the postwar American occupation of Japan, which lasted from September 1945 to April 1952.13

While the press controls of the American occupation were milder than those of wartime Japan, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), General Douglas MacArthur, still controlled all Japanese media under a Civil Censorship Detachment.14 In 1948, SCAP had decreed that it would only licence foreign books if “they demonstrably would further the objectives of the occupation”; that is, if they would help democratize and demilitarize Japanese society.15 Soon after, SCAP began to periodically present lists of foreign books to Japanese publishers who could then bid against each other to try to acquire the printing licenses.16 By 1950, the SCAP Translation Program had also been created to help publish edifying Western literature in Japanese. One publisher which specialized in these Western translations was Mikasa Shobo, which already had a sizable female readership, having published works such as Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (1869), a Japanese bestseller in 1950. It was here, on the solicitation of the publishing house, that Muraoka eventually submitted her translation of Anne of Green Gables in 1951.17 American influence over the Japanese book market in the name of promoting democracy was thus important in popularizing and translating Western female authors in Japan, and therefore crucial in getting Anne to print. Indeed, General MacArthur himself played a surprisingly active role in promoting such authors. For example, on a recommendation from his wife Jean, MacArthur had vigorously pressed for a quick translation of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s The Long Winter (1940), one of the novels in her Little House on the Prairie series which, like Anne, mixed coming-of-age stories with the individualistic possibilities conjured up by their unconfined rural settings.18

As for Muraoka, she would go on to translate other Western novels, including a further fifteen of L.M. Montgomery’s books. In 1953, on Muraoka’s advice, the original Anne was also included in Japan’s new national school curriculum, where it would eventually be read by millions of junior high students over the following decades.19 But had Muraoka not discovered Anne in 1939, the novel may not have gone on to achieve the success in Japan that it has.

This background also makes it clear that while Canadian onlookers may praise Anne’s popularity “in the eyes of ordinary Japanese,” this predominantly refers to a young, female audience. As literary scholar Uchiyama Akiko has observed, Muraoka self-consciously translated Akage no An to fit the literary conventions of the extant Japanese “girls’ novels” (shōjo shōsetsu) genre, whose roots date back to the girls’ magazines of the late-Meiji era (1900–1912).20

The result can be seen in the demographics of those Japanese who have visited Prince Edward Island. As literary critic Calvin Trillin remarked of his own experiences in 1996, the visitors he saw did not include “many businessmen” nor (perhaps more surprisingly) “many families with ten-year-old girls.” Instead, they were “mainly single women in their late teens and twenties who are doing office work for a few years before they marry and begin a family.”21 This demographic observation also seems to hold true for those Japanese fans unable to travel to Canada. In 1963, for example, the Charlottetown Guardian ran an article from twenty-two-year-old Harada Ayako—“who is working in an office while studying”—and who was looking for an Island pen pal, “having become interested in P.E.I. from the internationally famous novel, ‘Anne of Green Gables.’”22 Likely, these are women who had read Anne as part of their schooling and wished to nostalgically relive their childhoods before entering the unglamorous world of adulthood.

Additionally, it is worth recognizing that Muraoka’s Anne, like all works in translation, is partly an adaptation of Montgomery’s original. One telling revision is Muraoka’s approach to gender roles within the story. Many later commentators have been keen to paint the novel as having inspired female liberation in Japan. “Faced with a society in which their own lives and careers are rigidly circumscribed,” the above-cited Ottawa Citizen article reported, many Japanese see Anne as “a spunky young girl who was able to surmount the patriarchal and hierarchical constraints imposed upon her, while still deferring to her elders.”23 “Like Anne Shirley, Japanese women live in an extremely conservative society in which all actions are strictly bound by convention,” Douglas Baldwin argued in 1993, quoting a Japanese scholar to allege that “Japanese women admire Anne Shirley’s feistiness as an antidote to the passivity instilled in Japanese women.”24 But if Anne has been read as a rather blatant work of female liberation in Japan, it is a reading that has little to do with Muraoka’s original (and still definitive25) translation. As an example, Uchiyama has noted that Muraoka makes a notable omission at Anne’s climax. In Montgomery’s original, Gilbert Blythe turns down a teaching position at Avonlea School so that Anne can take his place rather than go to school outside Avonlea. At this point, Mrs. Lynde emphasizes Gilbert’s self-sacrifice to Anne.26 In Muraoka’s translation, however, this passage is merely summarized, with the implication being that Anne had decided, independently, to cancel her university studies. Muraoka, in short, plays up Anne’s archetypically “feminine virtues” of modesty and self-sacrifice while downplaying the same traits in her male counterpart. As Uchiyama notes, overall, Muraoka “generally accepts gender roles in Japanese society, and believes that a woman who has a family should not neglect her domestic duties.” This does not mean that Muraoka “believed that women should be confined to the domestic sphere,” but it was in keeping with her “middle way” approach to gender relations. “Her translation,” Uchiyama concluded, “is a ‘Muraoka An,’ deeply inflected with her views of literature, language, gender and society.”27 In the end, while the novel may have been Montgomery’s, the words which so engaged its initial Japanese readers were Muraoka’s.

In short, while Anne clearly resonates with Japanese readers given its foreign appeal, this does not necessarily mean that they fully relate to either L.M. Montgomery’s original vision or to life in Prince Edward Island. As historian David Weale once reasoned, Montgomery’s “genius” was her ability to create, against an Island backdrop, “a truly universal heroine, who represents for all the conquest of youthful idealism and spirit over the tedious preoccupations of adult practicality,” relatable whether one lived in “Prince Edward Island, Japan, or Scandinavia.”28 This conclusion implies it was the book’s generalities in terms of setting (the bucolic countryside) and archetypes (the precocious young heroine), and not its specificities (Prince Edward Island and Anne Shirley), that initially appealed to Japanese readers. In other words, Anne succeeded in Japan not only due to the quality of the original text, but because there was a pre-existing social context to help make it legible for Japanese readers. It is likewise possible to overstate Montgomery’s prose or the Island’s physical presence as the sole ground for the book’s success, given the equally vital role played by Muraoka’s championing and the priorities of SCAP’s censors as intermediaries in getting the work to Japanese audiences. The book was, in part, a mediated and subsidized success in Japan.

This last point is especially relevant if we consider Anne’s competitors in postwar Japan. In 1979, a well-known anime adaptation of Akage no An was completed.29 This was the first production in Nippon Animation’s World Masterpiece Theatre line, which serialized the adaptation of a classic Western story every year from January to December. For the time, the anime was lavishly produced (including work by animators Miyazaki Hayao and Takahata Isao, later to become famous as the founders of Studio Ghibli).30 However, the World Masterpiece series had (under a different name) been in continuous production since 1969, and it is telling what one of its previous offerings had been. In 1974, Zuiyo Eizo (Nippon Animation’s predecessor) began production of Heidi, Girl of the Alps, an adaption of the Swiss writer Johanna Spyri’s novel Heidi (1881).31 The novel’s plot—a five-year-old orphan is sent by her aunt to live with her reclusive uncle in a small house high in the Alps—bears a striking similarity to the life of Anne Shirley, and like Akage no An the resulting anime was a success, easily crushing its competitors. Notably, one of the anime competing with Heidi was Matsumoto Leiji and Nishizaki Yoshinobu’s space opera the Space Battleship Yamato (1974), which had its run cut short after suffering low ratings against Heidi. Today, Yamato is usually judged a classic of Japanese science fiction, much referenced, parodied, and reimagined in Japanese popular culture.32 But at the time, there was no doubt which program had captured the public’s imagination. Years later, it became something of a running joke by many workers in the anime industry to tell how they had been forced to gather around a secondary television set to see Yamato while the rest of their families had been watching Heidi.33

This was only the tip of “Heidi-mania.” As the previously noted popularity of Little Women and The Long Winter demonstrated, Spyri’s novel fit a wider pattern of female-oriented foreign media focused on antimodern themes and bucolic landscapes finding lasting fame in Japan.34 In 2001, for example, as another adaptation of Heidi was about to be released, the Japan Times reflected on the book’s enduring popularity, concluding that its rural themes were the prime attractions:

Perhaps because it is more relentlessly urban than most modern industrial countries—thanks to its inhospitable geography—Japan is also more devoted than most to the ideal of an unspoiled rural life. The faster the foreground fills up with ugly concrete structures and electricity cables, the more doggedly the country’s city-dwellers focus on the splendid peaks and forests in the background. ... In the same way, Japanese still tend to think of themselves as a rugged, simple people, unusually attuned to natural beauty and seasonal rhythms and somehow undefined by their own unsightly cities and artificial urban lifestyles. It is not really a contradiction. The intensity of the one experience—high-speed, neon-lit, money-driven urban life—logically generates a celebration of its opposite.35

Nor is this a uniquely Japanese fixation. Despite its own urbanization, Canada too often imagines itself to be an indelibly rural country and has long yoked its nationalism to naturalist themes. One need only consider present-day awareness of the coureur de bois, Hudson’s Bay Company, Group of Seven, or Canada’s own passion for Anne.36 Despite culturally deterministic views by critics such as Baldwin that an inbuilt sense of the natural world makes the Japanese unduly open to “Montgomery’s vivid descriptions and idealization of nature,” the twentieth-century success of Anne can more simply be explained by the historical contingency of the nation’s postwar reconstruction and urbanization.37 As Japan rebuilt after the Second World War with rapid economic growth, this pull toward rural themes merely grew in tandem; while in 1950 only 38% of Japan’s population was urbanized, by 1975 it was 75%.38

The Japan Times article also linked Heidi’s popularity to similar Japanese affinities for Frances Hodgson Burnett’s novel The Secret Garden (1911) as well as for Anne. But Heidi allegedly remained something special: “in no other country has it had such a loyal following as in Japan, where translations of the original book and its two sequels, a popular animated television show, hotels and theme parks and the home movies of hundreds of thousands of Japanese pilgrims to Switzerland have made ‘Haiji’ [her Japanese pronunciation] a national icon.”39 Such reports closely follow the template of the allegedly unique popularity of Anne in Japan. Had a quirk of fate not allowed Muraoka Hanako to acquire Montgomery’s book from Loretta Shaw, Japan evidently had other works available in translation able to fill this niche. Clearly, there has always been a certain element of contingency in Japan’s appreciation of Anne of Green Gables.

The Quest of the Otaku: Japan’s Island Experience

In June 1992, Okuda Miki had had enough of her humdrum life at a Japanese publishing company. A lifelong fan of Anne of Green Gables, the twenty-six-year-old Okuda decided to quit her job, withdraw her life savings, pack her bags, and move to Cavendish, Prince Edward Island, for fifteen months to live out an “authentic” Anne Shirley experience in the protagonist’s home province. Upon her return, Okuda published numerous books based on her experiences, including a travelogue, Akage no An no Niwa De: Purinsu Edowādo-tō no 15 Kagetsu [In the Garden of Anne of Green Gables: Fifteen Months in Prince Edward Island] (1995).40

Okuda was a particularly extreme and atypical example of Japan’s fascination with Anne and her world, but in many ways her story can tell us much about Japanese perceptions of the Island and its inhabitants. In particular, Okuda’s journey fits into a wider pattern of Japanese tourism inspired by popular culture and serves as an interesting example of so-called otaku fandom in Japan, a phenomenon explored below. It also demonstrates the very selective ways in which Anne fans such as Okuda can frame the entire modern history of Prince Edward Island around the life of a single, fictional late-nineteenth-century orphan, fitting a pattern that can be found in many other descriptions of contemporary Prince Edward Island and its inhabitants in Japanese culture.

To briefly summarize, the birth of the Japanese otaku was a key development in Japan’s postwar consumer culture.41 The idea of “otaku” can most simply be translated into English as “fans,” and the pejorative connotation of its English equivalent (from the shortening of the word “fanatic”) is also contained in its Japanese counterpart. Otaku, the cliché goes, are asocial man-children perversely obsessed by anime and manga who live—like the stereotypical North American “nerd”—as parasitic layabouts in their parents’ basements. At first glance then, as literary scholar Brian Bergstrom admits, “it may seem unlikely that the emergence of [this] subcultural activity as an increasingly prevalent mode of cultural practice in the 1980s and 1990s would be relevant to a discussion of Japanese Anne of Green Gables fandom,” with its much earlier publication and arrival in Japan. Yet, as Bergstrom argues, “Okuda’s account of her time in Prince Edward Island provides crucial insights into the dynamics of Anne fandom as an embodied practice of pilgrimage, of inhabiting a real place as an extension of one’s engagement with a fictional world.”42 And much like similar initiatives back in Japan, Prince Edward Island tourist brokers have quickly realized the economic potential of encouraging such fandom.

A typical Japanese example of anime “pilgrimages” (seichi junrei) can be seen in relation to the production of the 2012 anime series Girls und Panzer.43 Set in an alternate universe where Second World War–style tank combat is practised as a popular sport, the anime’s action takes place at a fictional girls’ school in the real-life town of Ōarai in Ibaraki Prefecture, north of Tokyo. But like many modern anime, the show’s set designers paid careful attention to verisimilitude, and today fans can prowl the city’s modern streets to find those sites painstakingly recreated in the series.44

But far from being dismissive of these pop culture allusions, the city of Ōarai has been more than accommodating toward this form of “embodied fandom,” running a promotional campaign in parallel with the series and receiving a large influx of curious fans in return.45 Given that Ōarai was one of the cities impacted by the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (which also damaged the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in the nearby town of Ōkuma), the anime’s showrunners openly stated that they set the action at Ōarai to try to help the city get back on its feet.46 Similarly, Japanese tourists to Prince Edward Island such as Okuda see their visits as an attempt to “discover” sites such as Green Gables or Lover’s Lane as found in the books (and faithfully recreated by Miyazaki and Takahata for the 1979 anime).

As Bergstrom notes, Okuda’s travelogue

provides plenty of examples of Okuda encountering various natural features, museum exhibits and local events all over Prince Edward Island that she interprets as reinforcing the sense in which to be in Prince Edward Island is to see the world that Anne “saw,” as well as, implicitly, to see the world of Anne (and the world in general) through the eyes of the little girl she was when she first encountered this world via the books themselves.47

But there does, of course, remain a significant difference between those fans who visit the world of contemporary Ōarai as opposed to the now past world of Prince Edward Island circa 1908; Okuda’s travelogue implies that the Island at the start of the twentieth century and the Island at its end were, to all intents and purposes, indistinguishable.

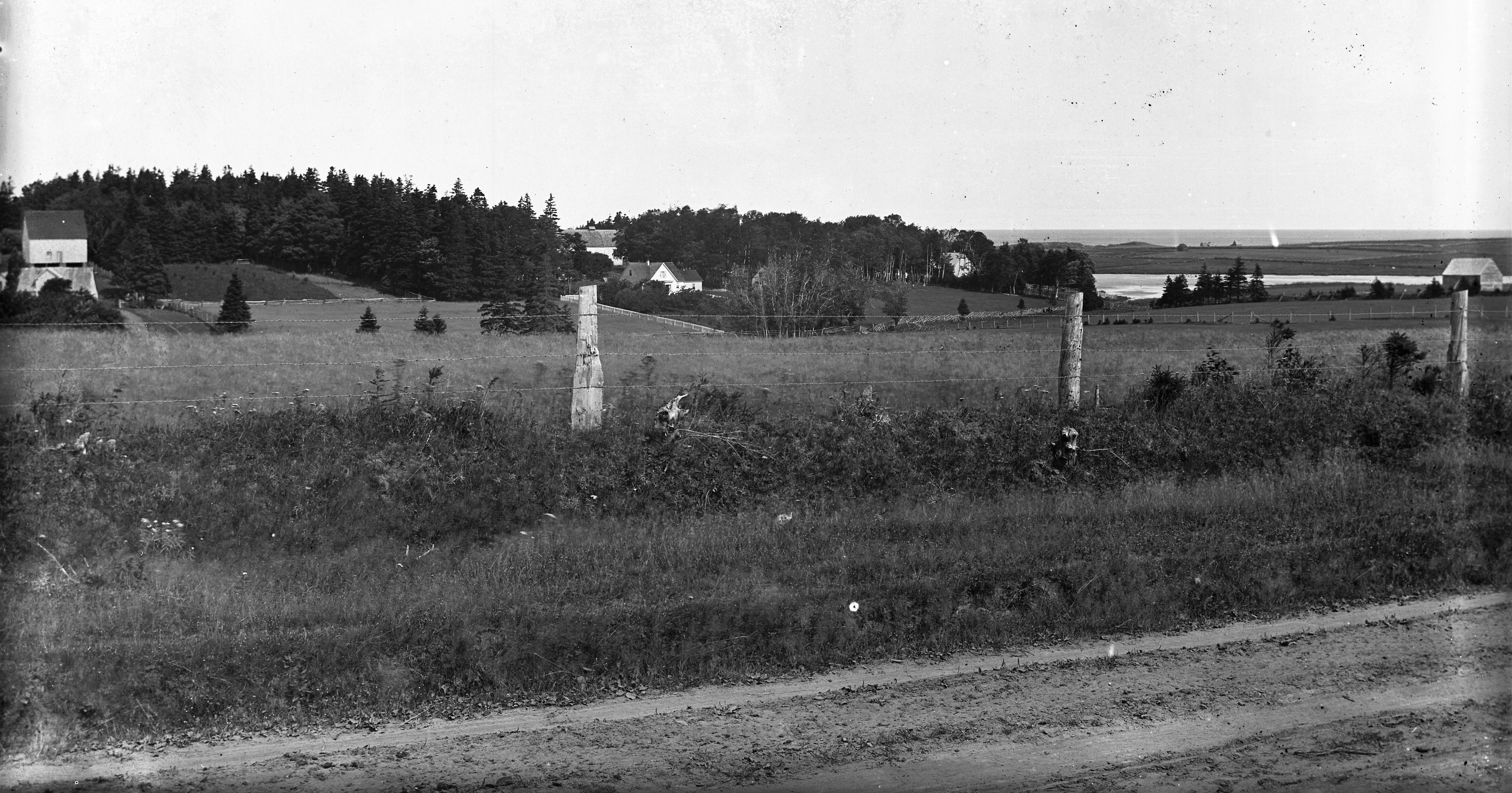

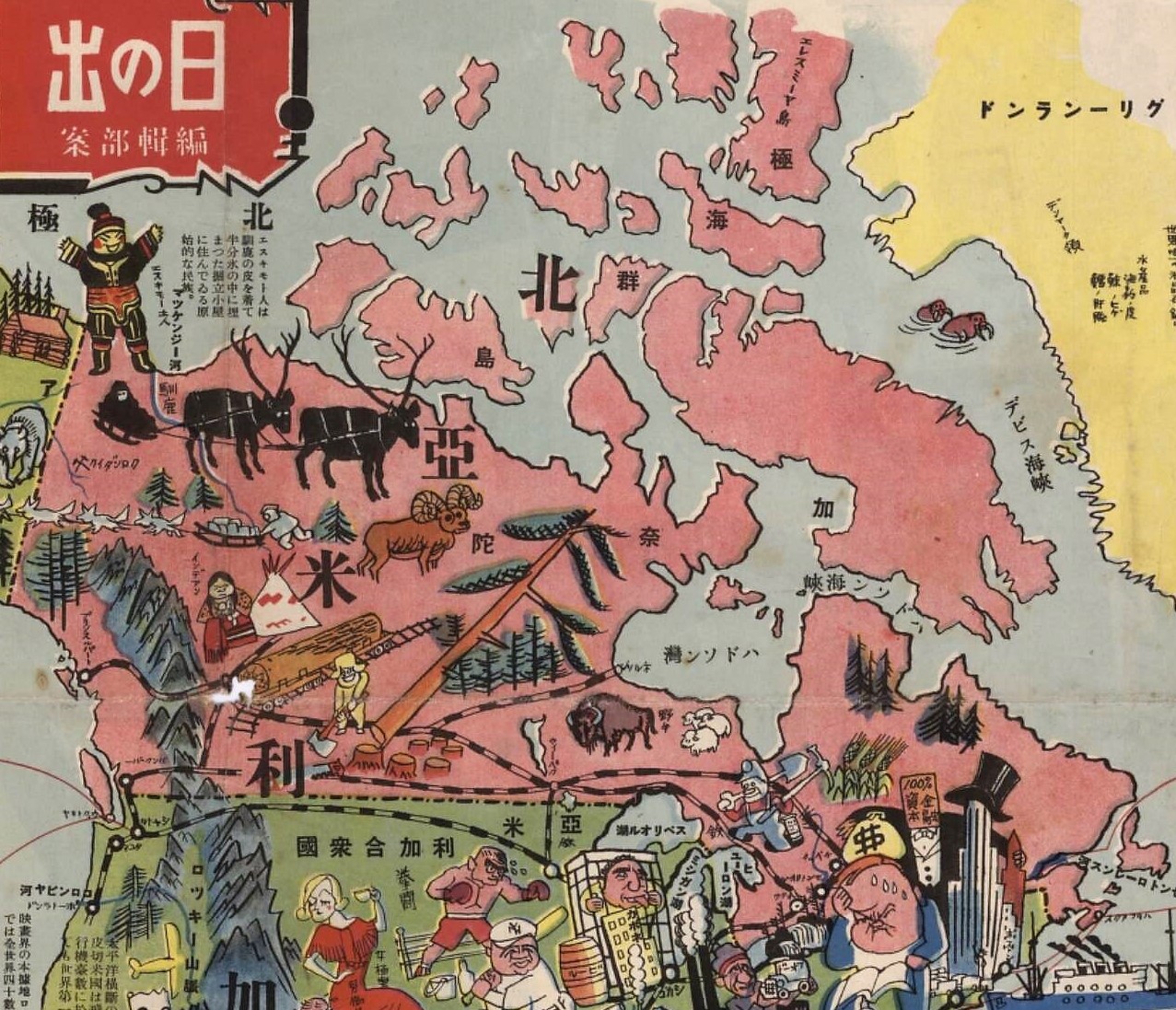

This raises a controversial aspect of Prince Edward Island’s tourism: its presentation of the Island as a picturesque, rural Eden where the spirit of Anne can be seen to frolic among the red sandstone cliffs and potato farms inhabited by good, hardy Islanders. While L.M. Montgomery did not invent this idea of Prince Edward Island as “the garden province”—the concept was, in fact, being used to promote the Island in the mid-nineteenth century—her works certainly did much to codify it, even during her own lifetime.48 Elsewhere, many Japanese in the early twentieth century had independently come to a similar conclusion. One satirical world map produced for the Japanese magazine Hinode in 1932, for example, portrayed Canada as inhabited by more animals than people.

There were no major cities illustrated (unlike in the United States to the south), nor were there any of the factory chimneys which covered the north of England. This was the “Canada” which remained familiar to most Japanese throughout the century. As the scholars Carin Holroyd and Ken Coates observed in 1996, contemporary Japanese stereotypes of Canada were “primarily influenced by visions of Canadian wilderness, the Anne of Green Gables stories, a fascination with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and a strong belief that the country is filled with loggers, miners and fishery workers.”49 In other words, Anne’s translation simply provided more grist for Japanese mills that were already operating at high speed.

Irrespective of the more complicated reality, this is the vision which appears time and again in many Japanese accounts of Prince Edward Island, portraying it as a quirky Canadian backwater. A selection of articles from the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of Japan’s largest newspapers, gives a good cross-section of views on this point. In 1991 (a year before Okuda’s sojourn), the newspaper described the Island, with perhaps a touch of pitying amusement, in the following terms:

PEI’s stagnant economy has meant the island, home to 128,000, has been spared the office towers and high-rise apartment buildings that have sprung up in big cities across Canada. Some native islanders have never been on an escalator; others joke about their trips to Toronto, where the shopping centers are full of the moving stairs. It’s not uncommon to run into the province’s Premier [Joseph Ghiz] at the ice cream shop in town, and entertainment sometimes means cruising to see who is working in the fields on Sunday.50

One particularly telling Japanese view of the Island can be found in the later travelogue produced by Yomiuri staff writer Murata Masayuki. “After a century, you’d expect the town and its residents’ way of life to have changed drastically,” Murata observed earnestly midway though his account, “but when I strolled around the town, I saw that many people there like things to stay the same.” In between discussing the stereotypical environmental highlights of the Island (“Green meadows and the reddish soil of potato fields create patchwork patterns over gentle hills, the Lake of Shining Waters glistens in the sunlight, and an old-style lighthouse overlooks the ocean …”) Murata also discussed his time as a guest at Dalvay by the Sea: “After I arrived, the hotel lost power due to strong winds, but I wasn’t averse to spending the night with a candle. It would be an experience suited to the island. Ultimately, the power came back a couple of hours later, but I can still remember the taste of the whiskey I had in the dark lobby in front of a fireplace.”51 Had Murata been describing the Prince Edward Island of the 1960s—before paved roads spanned the Island from tip to tip or the Confederation Bridge linked it to the mainland—then this perception of isolation may have been true.52 But this was the Island of 2013, which had paved roads, a bridge, and more to connect Islanders to the wider world. Even in Okuda’s travelogue, as in many such works, the author is depicted as a lone adventurer braving virgin territory. As Bergstrom noted, to read Okuda’s narrative and see her photographs one would swear she was the only Japanese visitor to the Island during her extended stay. Moreover, Okuda “goes to great lengths to transform the 1992 Prince Edward Island shown in the photos into an affective landscape continuous with the fictional, turn-of-the-century Prince Edward Island of Montgomery’s novels.”53

But are Islanders merely being hoisted by their own petards? This view—that Atlantic Canadian tourism boosters have shamelessly built up the region as a ridiculous anachronism, revelling in its kitschy insularity and the parochialism of its inhabitants—was the one provocatively raised by Ian MacKay’s The Quest of the Folk (1994), wherein he argued that contemporary Nova Scotian tourism had “embarked on a project of eliminating every visible sign of its being a twentieth-century society,” filling itself instead with bearded fishermen and craft fairs, even as the province went on to build “factories and warehouses, shopping malls and fast-food franchises.”54 And, besides, was all this Anne talk just a cynical attempt to market the mundane as the sublime? As historian Edward MacDonald has observed, “While the [promotional] literature purveyed Montgomery-esque images of an unspoiled paradise, local entrepreneurs began to fill the vistas with generic attractions that would be familiar pretty much anyplace in North America.”55 The more Prince Edward Island became generically “North American” and easily accessible after its mid-twentieth century globalization, the harder the tourist brokers asserted the Island was, in fact, remote and unique. In the words of historian Matthew McRae, tourism came to Prince Edward Island “with a built-in contradiction: The industry had become a harbinger of modernity, and yet relied on an anti-modern aesthetic for its very existence.”56

The successful marketing of this idea can be seen in its repetition by Islanders and its internalization by many Japanese visitors. As Bergstrom noted of Okuda’s travelogue, her dreams are actively abetted by the Island’s tourist industry, “which is organized to encourage this very pleasurable blurring of present and past, real and fictional in its museums and other facilities …”57 When the journalist Murata discovered there was neither a television nor phone in his room at Dalvay, he was politely told by the front desk clerk that “This hotel offers guests the opportunity to enjoy time separated from modernity,” as if this was the Island’s sole reason for existing. Murata would go on to visit the Charlottetown Farmers’ Market and uncritically quote the views of locals that they “love the life here surrounded by nature.”58 Some Japanese, however, have fought against this narrow vision of Prince Edward Island. When Numata Sadaaki, then the Japanese ambassador to Canada, visited Charlottetown in 2005, he made precisely this point to the Charlottetown Rotary Club, arguing that Islanders needed to promote themselves as more than just Anne and seafood, pointing to the province’s growing aerospace, biomedical, and valued-added processing fields as areas where they might cooperate with Japanese companies. “Be aggressive in making your sales pitch,” Numata urged, “be aggressive in making the point that there is much more to Prince Edward Island than this free-spirited red-haired girl.”59 When the Japanese firm Sekisui Diagnostics bought out Prince Edward Island’s former Diagnostic Chemicals Ltd. in 2011 and turned it into a financial success story, Numata’s exhortations appeared to be partially validated.60

Nevertheless, there is no doubt that Anne remains a keystone of Canada’s branding in Japan to this day. When then-Japanese Prime Minister Kaifu Toshiki inaugurated Canada’s new Tokyo embassy in 1991, as journalist Kate Taylor reported, he hoped the building would remind Japanese that there was more to Canada than its scenery, natural resources, and Anne. But, as Taylor noted, while Kaifu’s audience “dutifully tittered” at his admonishment, Japan’s Anne “cult” was already “firmly rooted and blossoming.”61 As political scientist John Kirton wrote in 2008, the negative result of this single-minded “Anne of Green Gables vision” is that most Japanese will admire Canada for its “pristine natural environment, and abundant raw materials, but not as a pioneer in those areas that were expected to dominate the twenty-first century economy.”62 In the Japanese imagination, Prince Edward Island and Canada remain stuck in the (early) twentieth century as the rest of the world moves into the computer-driven “Asian Century” of the twenty-first.

Conclusion

In April 2019, four months before Princess Takamado arrived in Prince Edward Island, the Island Entertainment Expo was held at the Delta Hotel in Charlottetown. This was the Island’s response to events like Comic-Con—a place for fans of popular culture to get together, dress as characters from their favourite shows (“cosplay”), and meet the producers and actors who brought their shows to life. Like many fan conventions, the Expo also had a mascot, and, unsurprisingly, the design reflected the freckled visage of Anne Shirley in an anime-esque style, likely inspired by memory of the 1979 series.63

This was perhaps fitting. In the twenty-first century, Western popular culture has been widely influenced by anime, manga, and other Japanese entertainment. Indeed, the word “cosplay” is itself a Japanese portmanteau of “costume play.” The Island Entertainment Expo is merely one of the many things currently linking Prince Edward Island to Japan. To it can be added the Japanese students attending the University of Prince Edward Island (some of whom met Princess Takamado in 2019), the rising fortunes of Sekisui Diagnostics (quietly toured by the Princess shortly after her arrival), and—of course—the tourism encouraged by Anne of Green Gables and the books of L.M. Montgomery.

As this article has shown, Japanese appreciation of Anne was not unprecedented and was never inevitable. The book ultimately succeeded due to a combination of excellent timing—as SCAP’s democratization priorities and Japanese desires for postwar escapist entertainment aligned—combined with an existing tradition of shōjo literature, the prewar Canadian missionary presence, postwar urbanization, the rise of a Japanese consumer culture, and the willing advocacy and translation skills of Muraoka Hanako. As for Islanders, a focus on Anne proved to make good business sense. People wanted to see Anne, it was something Prince Edward Island could claim as its own, and the Island economy could use the money. Meanwhile, the works of female Anne otaku such as Okuda—an archetypal example of a “vocal minority”—reinforced the perception for Islanders that Japanese enjoyment of Anne and their tourism to the Island was more pervasive than was the case. As a result, it became useful for Islanders to exaggerate the antimodern aspects of their history that buttressed the Anne story, while marginalizing those that contradicted it.

But no matter what Japanese tourists or their Island hosts may have wished, Prince Edward Island has not remained a pre-industrial society, but has been buffeted by the same forces of “modernization” which jostled the rest of the twentieth-century world. “Island farmers were not peasants living in un-splendid isolation,” as historian Edward MacDonald has noted curtly. Nor can Island history be framed as a simple black-and-white dichotomy. “Modernization,” MacDonald continues, “was not some life force implanted by extraterrestrials. Nor, despite some later judgements, was it a sort of demon that devoured rural virtue.” It was a complex trend capable of inspiring both a hopeful future as well as stirring strong emotions for a vanished past.64 Could modernity bring prosperity to Islanders? This was what the Prince Edward Island government’s Comprehensive Development Plan in the 1970s sought to achieve, and in terms of tourism it tried to bring more visitors with more money to visit more places besides the “golden triangle” framing the Borden ferry, Charlottetown, and the village of Cavendish with its sand beaches and Green Gables. In this respect the plan was a failure; the land of Anne of Green Gables remains a lynchpin of the Island’s tourism, subject to visitation trends as the province’s traditional economic trades of fishing and farming continue to recede in importance.65

Despite Canada and Japan’s other differences, this is a reality many Japanese know all too well. Notwithstanding the prosperity of metropolitan centres such as Tokyo or Osaka, many Japanese communities and rural townships saw their fortunes dim in the twentieth century.66 Increasingly depopulated, facing an aging workforce, their traditional industries in decline, they too struggled to find a place for themselves in a globalized world. The town of Ashibetsu, set on the banks of the Sorachi River in the forests of Hokkaido, has a typical story.67 In the 1950s, it had a population of 76,000 and an economy based on coal mining. By the early twenty-first century, however, that number had shrunk to 19,800 as the mines were shuttered, the economy stagnated, and its citizens dispersed. To regain its fortunes, the town turned to tourism. In 1990, Ashibetsu opened a 156-hectare Canadian World theme park, the centrepiece of which was a replica of Green Gables, painstakingly recreated from the original in Cavendish. Built on credit during the Japanese “Bubble Economy” of the late 1980s, the park began to hemorrhage money after the bubble burst in 1991. Kept on life support as a free city-run attraction, in 2019 the park was saved from final closure after a major crowdfunding campaign raised over 2.5 million yen, and it was the park’s appeal as the place that “imitates Anne of Green Gables” which proved the crucial sales pitch. There is no small irony in the fact that one Japanese town’s response to the pressures of modernity was to rely on tourism and mimic a Prince Edward Island community using similar tactics to avoid a similar fate.68

Acknowledgements: In some respects, this article was written as part of an academic “exchange program.” Back in 2019, Kate Scarth submitted an article to The Island Magazine during my tenure as editor, one eventually published after my departure as “Born for City Life? L.M. Montgomery’s Urban Prince Edward Island” (Volume 86, Fall/Winter 2020). I thus felt it was only courteous to try to write an article for her own journal in return. The origins of the topic itself can be traced back to both a conversation I had with Matthew McRae, my successor at The Island Magazine, as well as in the research being conducted for my Ph.D. at the University of Ottawa under the supervision of Dr. Galen Roger Perras. Thank you both.

About the Author: Michael Pass grew up in Charlottetown and is a graduate of the University of Prince Edward Island. He completed his M.A. in history at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax and is currently undertaking his Ph.D. in history at the University of Ottawa where his research is focused on diplomatic relations between Canada and Japan during and immediately after the Second World War. His most recent publication is “A Black Ship on Red Shores: Commodore Matthew Perry, Prince Edward Island, and the Fishery Question of 1852–1853,” published in the journal Acadiensis in 2020.

Banner image derived from: Screenshot from Akage no An. 1979. Directed by Takahata Isao. Nippon Animation. All Rights Reserved.

- 1 Montgomery, SJ 5 (23 Sept. 1937): 206.

- 2 Campbell, “Travel Writing” 263.

- 3 For this event and its background see Meehan, Dominion 1–31.

- 4 For the relevant entry see Montgomery, CJ 2 (3 June 1909): 229–32. In fact, recounting the wreck of the Marco Polo for the Montreal Daily Witness in 1891 was the first prose publication L.M. Montgomery ever completed. See Montgomery, A Name 5–10.

- 5 “Japan’s Princess Takamado” A5; Neatby, “Cavendish Park Opens” A2; “Green Gables Heritage Place” A3. The author was in attendance for this last event.

- 6 Indeed, this article was written partially in response to the idea that Japanese enjoyment of Anne represents a “riddle for the ages” (a tone taken by many authors during the 1990s, including Douglas Baldwin, Kate Taylor, and Calvin Trillin in works cited here).

- 7 Sterling, “Anne of Green Pagodas” A17.

- 8 Paskal, “You’d Almost Think” PT1.

- 9 Baldwin, “The Japanese Connection” 124.

- 10 Ion, Cross in the Dark Valley 1–3.

- 11 Statement Amended by Author 20 October 2021.

- 12 Many previous writers have incorrectly given this date as 1954. See, for example, Baldwin 123; Taylor, “Anne of Hokkaido” C1; Thibodeau, “Japanese to Boost Visitors” A1.

- 13 Ion 24; 113–20; Uchiyama, “Muraoka Hanako’s Translation” 211–12. For more on the missionary connection see Akamatsu, “During and After the World Wars.”

- 14 For the creation and mandate of the Civil Censorship Detachment see Dower, Embracing Defeat 406–410. In his words, “Censorship was conducted though an elaborate apparatus within GHQ [SCAP] from September 1945 through September 1949, and continued to be imposed in altered forms until Japan regained its sovereignty.”

- 15 For SCAP policy on foreign books see History of the Non-Military Activities 191–2.

- 16 For this process see Far Eastern Commission, SCAP Press Release. 27 Sept. 1948.

- 17 Gammel, O’Malley, Hu, and Banwait, “An Enchanting Girl” 180–1; History of the Non-Military Activities 192. For more on occupation-era Japanese publishing and the role of American censorship in constraining it, see Dower 168–200; 405–40.

- 18 See Suzuki, “Japanese Democratization.” In fact, The Long Winter was in the first batch of ninety-one foreign books (and one of the few works of fiction) licensed to be published in Japan under SCAP. See Parrott, “91 American and British Books” 24.

- 19 Uchiyama 212; Gammel, O’Malley, Hu, and Banwait 181. For Anne’s addition to the Japanese school curriculum see also Akamatsu, “Japanese Readings of Anne of Green Gables” 210–11.

- 20 Uchiyama 212–17. As Japanese language scholar Sarah Frederick has noted, these Meiji-era magazines “evoked a sense of Japanese girls as national figures and also part of a cosmopolitan world culture of ‘girlhood,’” and often included foreign works in translation. The journal Shōjo no tomo [Girls’ Friend], for example, published an abridged version of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A Little Princess (1905) in 1920. See Frederick, “Girls’ Magazines” 22; 32–4.

- 21 Trillin, “Anne of Red Hair” 216.

- 22 “Pen Pals Are Sought” 5. Japanese readers writing to the Guardian looking for pen pals and information on Anne’s home province were not uncommon in the 1960s. One letter the paper published in full came from schoolgirl Akaji Nobue. “Please forgive me for my rudeness in bothering your busy hours,” the fifteen-year-old meekly apologized in her stilted English. She was a big fan of Anne of Green Gables but was having trouble finding information on Prince Edward Island, as “here are no adequate materials.” As a result, “I would appreciate getting a detailed map of your Island.” See Akaji, “Interested in P.E.I.” 6.

- 23 Sterling A17.

- 24 Baldwin 130.

- 25 As scholar Sean Somers concluded in 2008, Muraoka’s translation is “still the most influential and highly regarded,” despite the existence of more recent adaptions. See Somers, Flowers of Quiet Happiness 46.

- 26 For the original scene see Montgomery, AGG 425.

- 27 Uchiyama 218–21.

- 28 Weale, “‘No Scope’” 8.

- 29 For more on this adaptation see Dhanowa, “Animating Anne.”

- 30 Indeed, as scholar Raz Greenberg has noted, many of the characters and settings of Miyazaki’s later Studio Ghibli films—such as heroine Sheeta and the European-inspired steampunk world of Laputa: Castle in the Sky (1986)—are reminiscent of Anne, Heidi, and their own worlds from the World Masterpiece Theatre canon. See Greenberg, Hayao Miyazaki, 111–12.

- 31 Greenberg 37–42. For a comparison of Japanese receptions to both series and the World Masterpiece Theatre canon see Seaton et al., Contents Tourism in Japan 173–4.

- 32 For examples of the contemporary resonance of Yamato in Japanese popular culture see Ikuho, “From Mourning to Allegory”; Posadas, “Remaking Yamato, Remaking Japan.”

- 33 This included the famous anime director Anno Hideaki who later laughed that “A whole family would watch Heidi together. But as for Yamato, it was just me. But my father was soon tempted, too.” See Eldred, “Yoshinobu Nishizaki X Hideaki Anno.”

- 34 For more on works comparable to Anne of Green Gables in Japan see also Akamatsu, “Japanese Readings” 201–6.

- 35 “Heidi Gets a Makeover.”

- 36 For the idea of Canadians as a nation of people shaped by their “hardy” environment see, for example, Berger, Sense of Power 128–33. It should be noted that similar “agrarian myths” also had a long history in prewar Japan. See, for example, Gluck, Japan’s Modern Myths 178–204.

- 37 Baldwin 127–9. Indeed, writers should avoid Baldwin’s gross generalization that “Canadians can learn much about Japanese values by studying such small, rural communities as Prince Edward Island at the beginning of the twentieth century” (131). As Somers cautions, “In describing the prevalence of Akage no An … critics have a responsibility to avoid ethnic generalizations: Japanese people appreciate Anne because of …” (45).

- 38 Gordon, Modern History of Japan 249.

- 39 “Heidi Gets a Makeover.”

- 40 Bergstrom, “Avonlea as ‘World’” 224–5. See also Okuda, Akage no An no Niwa De.

- 41 For more on Japan’s otaku phenomenon see Galbraith, Struggle for Imagination.

- 42 Bergstrom 233.

- 43 For an overview and history of such “pilgrimages” see Okamoto, “Otaku Tourism.”

- 44 See “Ōarai: Ibaraki.”

- 45 Sherman, “Town Prepares for Returning Crowds.”

- 46 Seaton et al. 217–18.

- 47 Bergstrom 236.

- 48 See MacDonald, “A Landscape” 73–6.

- 49 Holroyd and Coates, Pacific Partners ix.

- 50 “Freckled, Fictional Orphan” 11.

- 51 Murata, “A Visit to Green Gables” 17.

- 52 For these factors in globalizing Prince Edward Island see MacDonald, If You’re Stronghearted 241–2; 381–3.

- 53 Bergstrom 236.

- 54 McKay, Quest of the Folk 274–5.

- 55 MacDonald, If You’re Stronghearted 274.

- 56 McRae, Manufacturing Paradise 212.

- 57 Bergstrom 236–7.

- 58 Murata 17.

- 59 Thibodeau A1. Numata also noted that while 400,000 Japanese visited Canada in 2004, only about 7,000 (1.7%) came to PEI. While these numbers have fluctuated over the years—there was, for example, a concerted “Anne of Green Gables—My Dream” promotion campaign held during the late-1980s which briefly boosted numbers—the Island has only ever been (in absolute numbers) a relatively minor draw for most Japanese coming to Canada.

- 60 Magner, “Entrepreneurship” B6. “Since 2011 our revenues have grown about 225 per cent,” as plant manager Brian Stewart boasted in 2018, adding that the PEI plant was more cost-competitive than those in Japan itself. See Canadian Press, “Boom Island” A3.

- 61 Taylor C1.

- 62 Kirton, “North Pacific Neighbours” 215. Nor was Kirton the first to note the limitations of this vision. As political scientist Lorne Kavic noted after Osaka’s Expo ’70, Canada’s exhibition “may well have stimulated Japanese public awareness of Canada, but tall timbers, the RCMP Band and Musical Ride, and performances of Anne of Green Gables reinforce long-standing popular images rather than providing a realistic insight into Canada’s multicultural mosaic with its quaint traditionalist component and its crude modernistic overtones.” See Kavic, “Canada-Japan Relations” 580.

- 63 See Island Entertainment Expo.

- 64 MacDonald, If You’re Stronghearted 226–7. See also McRae.

- 65 MacDonald, If You’re Stronghearted 314–18.

- 66 As of this writing, rural impoverishment was back in the news given the appointment of Suga Yoshihide as Japanese Prime Minister in September 2020. The son of strawberry farmers from Yuzawa in remote Akita Prefecture, Suga’s hometown (as the Japan Times noted) “captures key challenges his administration will face: Half the residents in the area are over 60. Depopulation and aging have meant a dramatic fall in tax revenue, pushing the town’s government, reliant on support from Tokyo, to consider merging with other towns in Akita Prefecture.” See Lies, Takenaka, and Gallagher, “Aging and Empty.”

- 67 Attempts at rural tourism were common in the 1980s and 1990s. The town of Iwasaki in Aomori Prefecture, for example, built a Santa Claus theme park; Ureshino in Saga Prefecture constructed a mock Edo-era town named Hizenyumekaido; and Obihiro, also in Hokkaido, built “Gluck Kingdom,” an outdoor museum focused on German culture. See Nihon Keizai Shimbun, “Answer to Economy Blues” 26.

- 68 For this reconstruction see Seaton et al. 151–2; Paskal, “You’d Almost Think” PT1; Hornyak, “Ghost Town” 31–2; ReadyFor: Canadian World.

Works Cited

Akaji, Nobue. “Interested in P.E.I.” The Guardian, 15 May 1963, p. 6.

Akamatsu, Yoshiko. “During and After the World Wars: L.M. Montgomery and the Canadian Missionary Connection in Japan.” The Looking Glass: New Perspectives on Children’s Literature, vol. 18, no. 2, 2015, https://ojs.latrobe.edu.au/ojs/index.php/tlg/article/view/647.

---. “Japanese Readings of Anne of Green Gables.” L.M Montgomery and Canadian Culture, edited by Irene Gammel and Elizabeth Epperly, U of Toronto P, 1999, pp. 201–12.

Baldwin, Douglas. “L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables: The Japanese Connection.” Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d’études canadiennes, vol. 28, no 3, 1993, pp. 123–33.

Berger, Carl. The Sense of Power: Studies in the Ideas of Canadian Imperialism, 1867–1914. 2nd ed., U of Toronto P, 2000.

Bergstrom, Brian. “Avonlea as ‘World’: Japanese Anne of Green Gables Tourism as Embodied Fandom.” Japan Forum, vol. 24, no. 2, 2014, pp. 223–25.

Campbell, Mary Baine. “Travel Writing and Its Theory.” The Cambridge Companion to Travel Writing, edited by Peter Hulme and Tim Youngs, Cambridge UP, 2002, pp. 261–78.

The Canadian Press. “Boom Island: Canada’s Smallest Province Enjoying a Buoyant Economy.” The Guardian, 23 May 2018, A3.

Dhanowa, Meriel. “Animating Anne: How Akage no Anne Recreates L.M. Montgomery’s Vision Through a Visual Medium.” L.M. Montgomery and Vision Forum Collection, https://journaloflmmontgomerystudies.ca/vision-forum/animating-anne.

Dower, John. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. Norton, 1999.

Eldred, Tim. “Yoshinobu Nishizaki X Hideaki Anno, 2008 Interviews.” Our Star Blazers, 20 June 2013, https://web.archive.org/web/20201119170540/https://ourstarblazers.com/vault/78/.

Far Eastern Commission. “More Foreign Books Offered to Japanese Publishers,” SCAP Press Release, 27 September 1948. Public Information (4.7), Folder 1. Records of the Far Eastern Commission, National Archives (United States), Archives Unbound, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5110350509/GDSC?u=otta77973&sid=GDSC&xid=8a18b2a7. Accessed 26 Mar. 2020.

“Freckled, Fictional Orphan Draws Japanese to Canada’s PEI.” Daily Yomiuri, 27 Nov. 1991, p. 11.

Frederick, Sarah. “Girls’ Magazines and the Creation of Shōjo Identities.” Routledge Handbook of Japanese Media, edited by Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Routledge, 2018, pp. 22–38.

Galbraith, Patrick W. Otaku and the Struggle for Imagination in Japan. Duke UP, 2019.

Gammel, Irene, Andrew O’Malley, Huifeng Hu, and Ranbir K. Banwait. “An Enchanting Girl: International Portraits of Anne’s Cultural Transfer.” Anne’s World: A New Century of Anne of Green Gables, edited by Irene Gammel and Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 2010, pp. 166–91.

Gluck, Carol. Japan’s Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period. Princeton UP, 1985.

Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan, 3rd ed., Oxford UP, 2014.

Greenberg, Raz. Hayao Miyazaki: Exploring the Early Work of Japan’s Greatest Animator. Bloomsbury Academic, 2018.

“Green Gables Heritage Place Expansion Opens in Cavendish.” The Guardian, 31 Aug. 2019, A3.

“Heidi Gets a Makeover.” Japan Times, 8 Apr. 2001. https://web.archive.org/web/20201119170314/https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2001/04/08/editorials/heidi-gets-a-makeover/#.X01SqYt7lPY.

Holroyd, Carin, and Ken Coates. Pacific Partners: The Japanese Presence in Canadian Business, Society, and Culture. James Lorimer and Company, 1996.

Hornyak, Tim. “Ghost Town: Japan’s Ill-Fated Canadian Theme Park Goes Bust.” Canadian Business, 30 Aug. 2004, p. 31–2.

Ikuho, Amano. “From Mourning to Allegory: Post-3.11 Space Battleship Yamato in Motion.” Japan Forum vol. 26, no. 3, 2014, pp. 325–39.

Ion, A. Hamish. The Cross in the Dark Valley: The Canadian Protestant Missionary Movement in the Japanese Empire, 1931–1945. Wilfrid Laurier UP, 1999.

Island Entertainment Expo. http://islandexpo.ca/.

“Japan’s Princess Takamado Returns to PEI.” The Guardian, 23 Aug. 2019, p. A5.

Kavic, Lorne. “Canada-Japan Relations.” International Journal vol. 26, no. 3, 1971, pp. 567–81.

Kirton, John. “North Pacific Neighbours in a New World: Canada-Japan Relations, 1984–2006.” Contradictory Impulses: Canada and Japan in the Twentieth Century, edited by Patricia Roy and Greg Donaghy, UBC P, 2008, pp. 207–30.

Lies, Elaine, Kiyoshi Takenaka, and Chris Gallagher. “Aging and Empty: Suga’s Hometown Highlights Japan’s Challenges.” Japan Times, 14 Sept. 2020, https://web.archive.org/save/https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/09/14/national/aging-japan-yoshihide-suga-yuzawa/.

MacDonald, Edward. If You’re Stronghearted: Prince Edward Island in the Twentieth Century. PEI Museum and Heritage Foundation, 2000.

---. “A Landscape ... with Figures: Tourism and Environment on Prince Edward Island.” Acadiensis, vol. 40, no. 1, 2011, pp. 70–85.

McKay, Ian. The Quest of the Folk: Antimodernism and Cultural Selection in Twentieth-Century Nova Scotia. McGill-Queen’s UP, 1994.

McRae, Matthew John. Manufacturing Paradise: Tourism, Development and Mythmaking on Prince Edward Island 1939–1973. 2004. Carleton University, MA dissertation.

Magner, Margaret. “‘Entrepreneurship Generating Global Recognition.’” The Guardian, 9 Feb. 2013, p. B6.

Meehan, John D. The Dominion and the Rising Sun: Canada Encounters Japan, 1929–41. UBC P, 2004.

Montgomery, L.M. Anne of Green Gables. L.C. Page, 1908.

---. The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901–1911. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston, Oxford UP, 2012.

---. A Name for Herself: Selected Writings, 1891–1917, edited by Benjamin Lefebvre, U of Toronto P, 2018.

---. The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery. Edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford UP, 1985–2004. 5 vols.

Murata, Masayuki. “A Visit to Green Gables: Exploring the Charms of Anne’s PEI and Beyond.” The Japan News [Yomiuri Shimbun], 8 Dec. 2013, p. 17.

Neatby, Stu. “Cavendish Park Opens in Presence of Royalty.” The Guardian, 29 Aug. 2019, p. A2.

Nihon Keizai Shimbun. “Answer to Economy Blues: Open a Theme Park.” Nikkei Weekly, 14 Dec. 1991, p. 26.

Noriko, Suzuki. “Japanese Democratization and the Little House Books: The Relation between General Head Quarters and The Long Winter in Japan After World War II.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly vol. 31 no. 1, 2006, pp. 65–86.

“Ōarai, Ibaraki: Home of Girls und Panzer.” The Infinite Zenith, 14 Jan. 2014, https://web.archive.org/web/20201112035821/https://infinitemirai.wordpress.com/2017/01/14/oarai-ibaraki-home-of-girls-und-panzer/.

Okamoto, Takeshi. “Otaku Tourism and the Anime Pilgrimage Phenomenon in Japan.” Japan Forum vol. 27, no. 1, 2015, pp. 12–36.

Okuda, Miki. Akage no An no Niwa De: Purinsu Edowādo-tō no 15 Kagetsu. Tokyo, Tokyo Shoseki, 1995.

Parrott, Lindsay. “91 American and British Books Bought for Publication in Japan.” New York Times, 15 June 1948, p. 22.

Paskal, Cleo. “You’d Almost Think You Were in Canada.” National Post, 9 Nov. 2002, p. PT1.

“Pen Pals Are Sought.” The Guardian, 16 Mar. 1963, p. 5.

Posadas, Baryon Tenso. “Remaking Yamato, Remaking Japan: Space Battleship Yamato and SF Anime.” Science Fiction Film and Television vol. 7, no. 3, 2014, pp. 315–42.

ReadyFor: Canadian World, https://readyfor.jp/projects/canadian-world.

Seaton, Philip A., Yamamura Takayoshi, Sugawa Akiko, and Jang Kyungjae. Contents Tourism in Japan: Pilgrimages to “Sacred Sites” of Popular Culture. Cambria P, 2017.

Sherman, Jennifer. “Town Prepares for Returning Crowds of 100,000+ Due to Girls and Panzer.” Anime News Network, 13 Nov. 2017, https://web.archive.org/save/https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interest/2017-11-13/town-prepares-for-returning-crowds-of-100000-due-to-girls-and-panzer/.123978.

Somers, Sean. “Anne of Green Gables/Akage no An: The Flowers of Quiet Happiness.” Canadian Literature, vol. 197, no. 197, 2008, pp. 42–60.

Sterling, Harry. “Anne of Green Pagodas.” Ottawa Citizen, 9 July 1999, p. A17.

Taylor, Kate. “Anne of Hokkaido.” Globe and Mail, 6 July 1991, p. C1-C3.

Thibodeau, Wayne. “Japanese to Boost Visitors, Says Envoy.” The Guardian, 20 Sept. 2005, p. A1.

Trillin, Calvin. “Anne of Red Hair: What Do the Japanese See in Anne of Green Gables?” L.M Montgomery and Canadian Culture, edited by Irene Gammel and Elizabeth Epperly, U of Toronto P, 1999, pp. 213–21.

Uchiyama, Akiko. “Akage no An in Japanese Girl Culture: Muraoka Hanako’s Translation of Anne of Green Gables.” Japan Forum, vol. 26, no. 2, 2014, pp. 211–12.

United States Government. History of the Non-Military Activities of the Occupation of Japan, Volume 5, Civil Liberties, Part 4, Freedom of the Press, 1945 to January 1951. National Archives and Record Administration, World War II Records Division, 1951[?].

Weale, David. “‘No Scope for Imagination’: Another Side of Anne of Green Gables.” The Island Magazine, no. 20, 1986, pp. 3–8.